Article topic: Personality Disorders Cluster A.

Author: Hala Qaryouti.

Keywords: Personality Disorders , Cluster A, Psychiatry, Mental disorder.

Linguistic Editor: Aroob Awwad Awwad.

Personality is a term derived from Greek word persona, originally used to describe the mask worn by theater players. With time, the term evolved to describe the person’s hidden inner psychological qualities. Today, personality is seen as a complex, not easily altered pattern of fixed, nonconscious psychological characteristics expressed automatically in all aspects of daily life to account for the individual’s behavior, pattern of perception, feeling, thinking and coping(1).

Although there is no unclouded differentiator between normal and pathological personality traits, the DSM-5 criteria summarizes a personality disorder (PD) as a pervasive, inflexible and enduring behavioral pattern that deviates markedly from expectations of the individual’s culture. This pattern manifests in at least two of the individual’s cognition, affect, interpersonal functioning and impulse control. All personality disorders have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, and although stable over time, they lead to distress in several aspects of daily functioning. The effect of any other mental disorders (i.e. psychotic spectrum of disease, depressive and anxiety disorders, and PTSD) as well as medical disorders and substance abuse should be excluded before making the diagnosis of a PD(2).

DSM-5 Personality disorders are grouped into three clusters (A, B, C). Paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders are included in cluster A, while cluster B includes antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders. Finally, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders fall under the umbrella of Cluster C.

Epidemiology

A study has shown that around 12% of people in a general population have a personality disorder (PD)(3). Data from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions estimated that approximately 14.8% of US adults have at least one personality disorder (4), while the WHO has estimated the prevalence of having any personality disorder to be 6.1% in total, divided among the 3 clusters (A, B, and C) as 3.6%, 1.5%, and 2.7%, respectively (5).

Risk factors

They can differ depending on the personality disorder, but in general, all PDs share the following risk factors :

- Young age (adolescence to early adulthood).

- Male sex.

- Being unmarried.

- Lower socioeconomic and education levels(6).

Etiology

The precise etiology of personality disorders is not clearly understood and can differ depending on the disorder. Nevertheless, several hypotheses have been suggested. For example, some psychoanalysts attribute these disturbances to failure of proper psychosexual development while others suggest that childhood trauma is a cause. This becomes especially apparent in patients with borderline and antisocial disorders who have intimacy and trust deficits co-related with childhood abuse and trauma. Cultural factors may also play a pivotal role in the development of personality disorders (7).

More recently, researchers have found genetic correlations in schizotypal, borderline and antisocial PD. Genes of interest under investigation are serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), and norepinephrine (5).

Cluster A Personality Disorders

Patients are described as odd, peculiar and withdrawn. They usually utilize defense mechanisms such as projection, magical thinking and intellectualization. All cluster A disorders have a familial association with psychotic disorders.

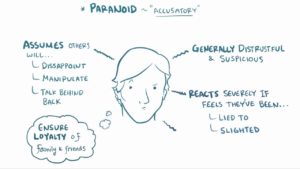

- Paranoid Personality Disorder (PPD)

Prevalence

PPD is a disorder characterized by constant suspicion of others. It is a personality disorder which hasn’t had its fair share of research mainly due to the paranoia trait in patients, creating obstacles in recruiting and keeping them in a study (8). However, several studies show calculated prevalence, such as the US Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, which showed PPD as the second most prevalent PD with 4.4% out of the total of 14.8% of US adults with personality disorders(9). Another study, conducted by Zimmerman and colleagues, has shown that 4.2% of general psychiatric outpatients meet criteria for PPD, 0.7% of whom have PPD as the only personality disorder(10).

Risk Factors

In addition to the risk factors in common to all PDs mentioned above, negative childhood experiences whether physical, sexual, or emotional abuse correlate to adult-onset PPD more than any other PD (11). However, PPD in late adolescence has only been associated with previous physical abuse (12). Demographic risk factors include a Black, Native-American or Hispanic ethnicity as evidenced by Connolly et. al in a sample of clients at a homeless drop-in center where PPD was the most common personality disorder(13).

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria(2)

To diagnose a patient with PPD, like all personality disorders, the change must start by early adulthood where the following criteria are met:

A. The patient is described as someone constantly suspicious of others and will display four (or more) of the following:

- Unjustified suspicion of others.

- Preoccupation with unjustified doubts about whether surrounding people are trustworthy.

- Reluctance to confide in others due to unnecessary fear of information being used for blackmail.

- Interpretation of benign remarks as threats with hidden messages.

- Unforgiving and bears grudges.

- Angrily counterattacks a perceived attack on character or reputation, not clear to others.

- Unjustified suspicions of spousal/partner infidelity.

B. All criteria mentioned must be present in the patient’s baseline character and not only during the course of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or depressive disorder with psychotic features.

Although the diagnostic criteria may seem clear-cut, PPD does not clinically present as an isolated PD as almost 75% of cases are accompanied by a comorbid personality disorder, (14) of which avoidant and borderline PD are the most common followed by narcissistic PD (15). Other frequent comorbidities are substance abuse (16) and panic disorder (17).

Treatment

There are no FDA-approved medications for PPD and systematic data is lacking regarding CBT, although some case studies support its potential effectiveness(18). However, psychiatrists must tread with caution regarding these positive results because PPD still remains one of the strongest predictors of aggressive behavior (19), treatment failure and dropout (20)(21).

Prognosis

Generally, cluster A patients, PPD patients in specific, have a worse prognosis than PD patients of clusters B and C (20). In addition, the long-term prognosis of PPD is not very positive because although its traits can decline by 46% from adolescence to early adulthood (22), it remains one of the three personality disorders most strongly associated with reduction in quality of life (23)(9) and decreased functioning, as measured by the GAF Scale (24), making patients more prone to depression despite intensive psychiatric treatment (20).

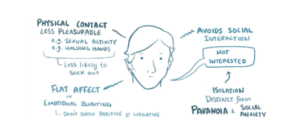

- Schizoid Personality Disorder (ScPD)

Prevalence

ScPD is characterized by asociality and preference of being alone. Although it has been discovered long enough to be listed in all editions of DSM, ScPD is the least common of the cluster A disorders, with studies suggesting that this disorder has a prevalence of less than 1% (8), and no significant difference in frequency between males and females(9). Other studies estimated the prevalence of ScPD as a sole PD among psychiatric patients to be 0.3% (25), while population-based estimates found a 1.7% prevalence of ScPD in Oslo, Norway (26) and a 0.8% prevalence in the United Kingdom (27).

Risk Factors

Major depressive disorder among children and adolescents is the strongest predictor of adult ScPD, and relates to it more than any other adult personality disorder (16).

On the other end, ScPD itself is a risk factor for developing other diseases. ScPD, as well as PPD, were found to be associated with dysthymia, mania, panic disorder with agoraphobia, social phobia and generalized anxiety disorder in a population-based study done by Grant et al. (28). ScPD has also been correlated with violent behavior (29), and even organic causes such as arthritis (30), obesity (31) and coronary artery disease, in two separate cohorts (32),(33). Finally, ScPD was found to be the second most common PD in patients with kleptomania. (9).

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria(2)

A. An omnipresent pattern of asociality and anhedonia in interpersonal settings, cognitive or perceptual distortions, and eccentric attitude starting early adulthood, manifested by four (or more) of the following:

- Patient neither desires nor enjoys close relationships, including being part of a family.

- Prefers solitary activities.

- Has little, if any, interest in having sexual experiences.

- Detached, emotionally cold with flat affect.

- Indifferent to praise and criticism.

- Has no close friends.

- Takes pleasure in few (if any) activities.

B. As with PPD, to diagnose a patient with ScPD, their behavioral traits should not occur exclusively during the course of other mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depressive disorder with psychotic features, or autism spectrum disorder, and is not caused by any medication side effects.

It is uncommon for a schizoid personality disorder patient to present willingly on their own unless prompted by family members, or presenting for a co-occurring disorder. This is attributed to the egosyntonic nature of personality disorders in general, which makes patients view other people as the problem instead acknowledging their own behavioral flaws(4).

Treatment

There is no approved modality for the management and treatment of schizoid personality disorder. However, some studies suggest that psychotherapy can help improve the secluded nature of patients with the clinician’s help to considerately direct the patients to their behavioral abnormalities and encourage them to implement a new healthier behavioral pattern. Pharmacotherapy can be of use for co-morbid disease states, such as SSRIs for depression (34)

Prognosis

In a 2-year follow-up study of personality disorder symptoms in older adolescent psychiatric outpatients, ScPD was the most stable over time (35). Nonetheless, it has been found to cause considerable reduction in quality of life (23), as well as emotional disability (9).

- Schizotypal Personality Disorder (SPD)

Prevalence

SPD is characterized by patients’ eccentric beliefs, and is the closest PD to schizophrenia. Community studies report rates from 0.6% in Norwegian samples to 4.6% in U.S. samples. The prevalence of schizotypal personality disorder in clinical populations is 0%-1.9%, with a higher estimated prevalence of 3.9% in the general population as found in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions(4). A twin study also found that positive or psychotic-like symptoms in SPD were independently heritable from the negative or deficit symptoms (3).

Risk Factors

Genetic and physiological risk factors are considered since schizotypal personality disorder shows a familial pattern, especially that they are more prevalent among the first-degree relatives of individuals with schizophrenia than among the general population(2).

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria (2)

A. SPD patients will have a sustained pattern of social and interpersonal deficits exhibited as discomfort and inability to form intimate relationships, cognitive or perceptual distortions, and an eccentric behavior indicated by five (or more) of the following:

- Ideas of reference: misinterpretation of normal quotidian incidents done by the patient (should be differentiated from delusions of reference, where the whole incident is imagined by the patient and is not real.)

- Odd beliefs or magical thinking inconsistent with subcultural norms and affecting behavior. They can include superstition, belief in clairvoyance (having supernatural powers), telepathy, or “sixth sense” in adults. In children and adolescents, bizarre fantasies or preoccupations may be seen.

- Unusual perceptual experiences such as bodily illusions.

- Odd thinking and speech. Speech can be unusually phrased and is often vague, but without actual derailment or incoherence.

- Suspicion or paranoid ideation.

- Inappropriate or constricted affect.

- Odd or peculiar behavior or appearance.

- Lacking close friends and confidants other than first-degree relatives.

- Excess social anxiety that does not become better with familiarity.

B. As with other personality disorders, the odd behavior must be present as the patient’s baseline and not only during the course of schizophrenia, a bipolar disorder or depressive disorder with psychotic features, another psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder to diagnose SPD.

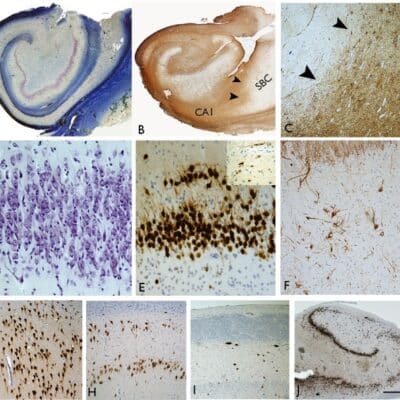

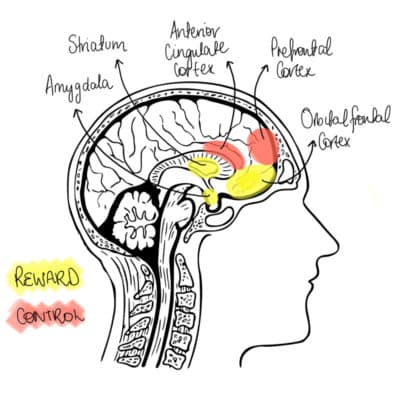

Imaging Abnormalities

Despite the fact that patients with SPD are spared the chronic psychosis of schizophrenia, both disorders are closely related. This is shown by similar neuroimaging and neurochemical evidence, treatment and outcome characteristics(36). Like schizophrenic patients, SPD patients show focal cognitive impairment involving working memory, verbal learning, as well as sustained attention deficits and reductions in temporal lobe volume, but without the frontal volume reductions found in some studies of schizophrenic patients(36).

On neuroimaging, ventricular enlargement has been observed in samples of clinically identified SPD patients (37), relatives of schizophrenic patients (38) and schizotypal volunteers. Furthermore, abnormalities such as reduced volume in temporal lobe and hippocampus have been found in schizotypal patients, as have been in schizophrenic patients (39). SPD patients also perform poorly in tests of executive function sensitive to frontal lobe damage, such as the Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST) (40).

Treatment

Several studies suggest that treatment with neuroleptic medications can reduce some of the symptoms of schizotypal personality disorder, particularly the psychotic-like symptoms and social anxiety associated with the disorder (41). Studies with agents such as thiothixene (41), haloperidol (42), and risperidone (43) may be helpful in alleviating the symptomatic distress of schizotypal personality disorder.

Prognosis

A study conducted by Henriques-Calado and Duarte-Silva in 2020 showed that a future diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease can be predicted by, but is not limited to, SPD in females (44). Also, OCD comorbid with SPD is associated with poorer treatment outcome (45).

[Read more]

References

- Millon T. Invited Essay What Is a Personality Disorder? J Pers Disord. 2016;30(3):289–306.

- American Psychiatric Association 2013. DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS FIFTH EDITION DSM-5. In.

- Skjernov M, Bach B, Fink P, Fallon B, Soegaard U, Simonsen E. DSM-5 Personality Disorders and Traits in Patients with Severe Health Anxiety. J Nerv Ment Dis [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2021 Jan 6];208(2):108–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31821216/

- Maniacci MP, Sperry L. Neurocognitive disorders. Psychopathology and Psychotherapy: DSM-5 Diagnosis, Case Conceptualization, and Treatment. 2014. 335–355 p.

- Ma G, Fan H, Shen C, Wang W. Genetic and Neuroimaging Features of Personality Disorders: State of the Art [Internet]. Vol. 32, Neuroscience Bulletin. Science Press; 2016 [cited 2021 Jan 4]. p. 286–306. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5563771/?report=abstract

- Zhang TT, Huang YQ, Liu ZR, Chen HG. Distribution and risk factors of disability attributed to personality disorders: A national cross‑sectional survey in China. Chin Med J (Engl) [Internet]. 2016 Aug 5 [cited 2021 Jan 4];129(15):1765–71. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4976561/?report=abstract

- Fariba K, Gupta V, Kass E. Personality Disorder. 2020 Nov 20 [cited 2021 Jan 4]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556058/

- Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A Personality Disorders: Schizotypal, Schizoid and Paranoid Personality Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010 Dec;32(4):515–28.

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004 Jul;65(7):948–58.

- Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D. The frequency of personality disorders in psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008 Sep;31(3):405–20, vi.

- Bierer LM, Yehuda R, Schmeidler J, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Silverman JM, et al. Abuse and neglect in childhood: relationship to personality disorder diagnoses. CNS Spectr. 2003 Oct;8(10):737–54.

- Golier JA, Yehuda R, Bierer LM, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Schmeidler J, et al. The relationship of borderline personality disorder to posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Nov;160(11):2018–24.

- Connolly AJ, Cobb-Richardson P, Ball SA. Personality disorders in homeless drop-in center clients. J Pers Disord. 2008 Dec;22(6):573–88.

- Gore WL, Widiger TA. The DSM-5 dimensional trait model and five-factor models of general personality. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013 Aug;122(3):816–21.

- Morey LC. Personality disorders in DSM-III and DSM-III-R: convergence, coverage, and internal consistency. Am J Psychiatry. 1988 May;145(5):573–7.

- Ramklint M, von Knorring A-L, von Knorring L, Ekselius L. Child and adolescent psychiatric disorders predicting adult personality disorder: a follow-up study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57(1):23–8.

- Reich J, Braginsky Y. Paranoid personality traits in a panic disorder population: a pilot study. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(4):260–4.

- Kellett S, Hardy G. Treatment of paranoid personality disorder with cognitive analytic therapy: a mixed methods single case experimental design. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2014;21(5):452–64.

- Berman ME, Fallon AE, Coccaro EF. The relationship between personality psychopathology and aggressive behavior in research volunteers. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998 Nov;107(4):651–8.

- Karterud S, Pedersen G, Bjordal E, Brabrand J, Friis S, Haaseth O, et al. Day treatment of patients with personality disorders: experiences from a Norwegian treatment research network. J Pers Disord. 2003 Jun;17(3):243–62.

- Kvarstein EH, Karterud S. Large variations of global functioning over five years in treated patients with personality traits and disorders. J Pers Disord. 2012 Apr;26(2):141–61.

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Skodol AE, Hamagami F, Brook JS. Age-related change in personality disorder trait levels between early adolescence and adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000 Oct;102(4):265–75.

- Cramer V, Torgersen S, Kringlen E. Personality disorders and quality of life. A population study. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47(3):178–84.

- Crawford TN, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Kasen S, First MB, Gordon K, et al. Self-reported personality disorder in the children in the community sample: convergent and prospective validity in late adolescence and adulthood. J Pers Disord. 2005 Feb;19(1):30–52.

- Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;162(10):1911–8.

- Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 Jun;58(6):590–6.

- Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, Roberts A, Ullrich S. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry. 2006 May;188:423–31.

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Patricia Chou S, June Ruan W, et al. Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Psychiatr Res. 2005 Jan;39(1):1–9.

- Pulay AJ, Dawson DA, Hasin DS, Goldstein RB, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP, et al. Violent behavior and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;69(1):12–22.

- McWilliams LA, Clara IP, Murphy PDJ, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Associations between arthritis and a broad range of psychiatric disorders: findings from a nationally representative sample. J pain. 2008 Jan;9(1):37–44.

- Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2008 Apr;70(3):288–97.

- Moran P, Stewart R, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Bhugra D, Jenkins R, et al. Personality disorder and cardiovascular disease: results from a national household survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;68(1):69–74.

- Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA, Petry NM. DSM-IV personality disorders and coronary heart disease in older adults: results from The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol And Related Conditions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007 Sep;62(5):P295-9.

- Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004 Oct;70(8):1505–12.

- Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Allot KA, Clarkson V, Yuen HP. Two-year stability of personality disorder in older adolescent outpatients. J Pers Disord. 2004 Dec;18(6):526–41.

- Kirrane RM, Siever LJ. New perspectives on schizotypal personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2(1):62–6.

- Siever LJ, Rotter M, Losonczy M, Guo SL, Mitropoulou V, Trestman R, et al. Lateral ventricular enlargement in schizotypal personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1995 Jul;57(2):109–18.

- Silverman JM, Smith CJ, Guo SL, Mohs RC, Siever LJ, Davis KL. Lateral ventricular enlargement in schizophrenic probands and their siblings with schizophrenia-related disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1998 Jan;43(2):97–106.

- Downhill JEJ, Buchsbaum MS, Hazlett EA, Barth S, Lees Roitman S, Nunn M, et al. Temporal lobe volume determined by magnetic resonance imaging in schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001 Mar;48(2–3):187–99.

- Lenzenweger MF, Korfine L. Perceptual aberrations, schizotypy, and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20(2):345–57.

- Goldberg SC, Schulz SC, Schulz PM, Resnick RJ, Hamer RM, Friedel RO. Borderline and schizotypal personality disorders treated with low-dose thiothixene vs placebo. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986 Jul;43(7):680–6.

- Hymowitz P, Frances A, Jacobsberg LB, Sickles M, Hoyt R. Neuroleptic treatment of schizotypal personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 1986;27(4):267–71.

- Szigethy EM, Schulz SC. Risperidone in comorbid borderline personality disorder and dysthymia. Vol. 17, Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. United States; 1997. p. 326–7.

- Henriques-Calado J, Duarte-Silva ME. Personality disorders characterized by anxiety predict Alzheimer’s disease in women: A case-control studies. J Gen Psychol. 2020;147(4):414–31.

- Thiel N, Hertenstein E, Nissen C, Herbst N, Külz AK, Voderholzer U. The effect of personality disorders on treatment outcomes in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorders. J Pers Disord. 2013 Dec;27(6):697–715.

- Cluster A personality disorders. Osmosis. Available at Osmosis