Title: Craniopagus Twins

Author: Ghayda’a Netham Al-Majali

Keywords: congenital anomaly , newborn , Obstetrics

Scientific Editor: Dr. Omar Jbara

Linguistic Editor:

Overview

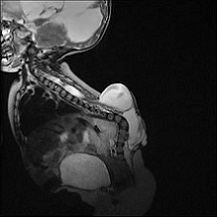

Craniopagus twins (CPT) are a rare congenital malformation or dysmorphism in which twins are conjoined and fused at the cranium (Head), accounting for only 2%–6% of conjoined twins, with an incidence once in every 0.6 to 2.5 million lives births (1)(2). CPT is predisposed more in females than males with a ratio of 3:1 although this has not been correlated with any cause of the condition (3). Mortality rate of CPT is 40% stillborn and 33% die in perinatal period (4).

The skulls are often joined in homogeneous regions on each twin in both vertical and angular directions (5). Conjoined brain tissue, connected arteries and veins, and defects in the skull and Dura make surgery technically challenging and difficult (6). Although there is high prenatal and postnatal mortality for CPT, successful separation has become more common due to advances and improvements in neuroimaging, neuro-anesthesia, and neurosurgical techniques (7)(8).

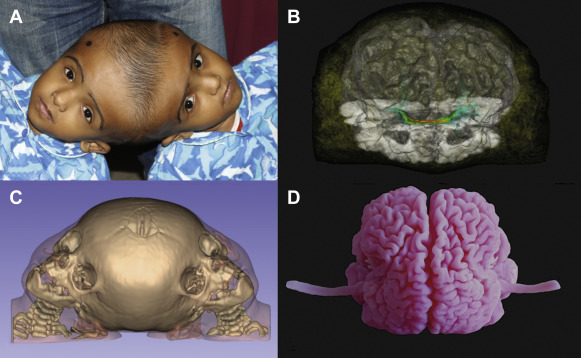

Neuroimaging, including CT, MRI, and conventional angiography, plays an important role in mapping the connected arterial and venous structures, brain parenchyma, calvaria, and Dura (9)(10).

Digital and physical 3D models arised from CT and MRI data are important tools for operative planning and as a guide in the operating room (6).

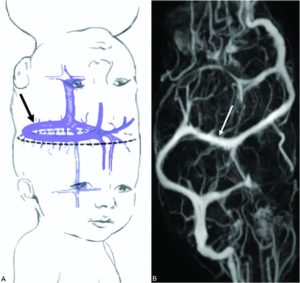

Understanding the shared vascular anatomy is important for surgical planning because separating common vessels is associated with complications and manifestations such as thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, infarction, and hemorrhage (11).

Separation can take place in single or multistage procedures and has improved as the understanding of the physiology, surgical techniques, and technology of CPT have evolved(12).

So the preoperative radiologic evaluation of CPT, including the anatomy, classification systems, and surgical management should be all reviewed, that is important for the radiologist to understand in addition to consultation for multiple successful CPT separations with an experienced neurosurgical specialist in CPT (2).

Moreover, Separation of conjoined twins poses several technical, legal, religious, moral and ethical issues (13).

Etiology

The cause of the conjoined Twins is unclear; incomplete fission and fusion have been proposed by embryologists and there are no known environmental or genetic factors (4).

Embryology

The monoamniotic, monochorionic type of monozygotic twinning has the highest potential for leading to conjoined twins (Kaufman, 2004), The two main theories of how monoamniotic monozygotic twins conjoin are the “fission” and “fusion” theories (14).

Fission theory proposes an incomplete cleavage or cleavage of the embryo at the primitive streak stage, resulting in conjoined embryos, this theory explains the apparent increase in the incidence of inversion and mirror imaging in conjoined twins, because a dividing cell or cell mass maintains mirror imaging (15).

The fusion theory suggests that embryos return to and rejoin at vulnerable sites after complete initial separation, this theory explains the different angles at which conjoined twins can be fused, along the dorso-ventral or rostro-caudal axis (14).

Anatomy

CPT are conjoined only at the calvaria, without involvement of the foramen magnum, skull base, vertebrae, or face. Other conjoined twins variations involving the head include cephalopagus (which involve the brain, face, thorax, and upper abdomen), parapagus diprosopus (which involve 2 faces on 1 head with 1 body), and rachipagus (which means joined dorsally along the vertebra and occasionally along the occiput) (2).

Conjunction is rarely symmetric and it may involve any portion of the head, including underlying structures such as meninges, venous sinuses, or cortex. Configuration can vary on the basis of the attachment location, degree of rotation and angulation between the 2 twins, which will determine the anatomy and difficulty of separation (2).

Classification System

The first classification system was developed by O’Connell, in which CPT were classified as partial or total (16).

Total CPT share an extensive surface area with widely connected cranial cavities (In which two brains can be thought of as being located within one skull and a series of gross intracranial malformations and abnormalities develop) (16).

There are 3 varieties can be recognized in the total form, these include: (16)

- Deformity of the skull base,

- Deformity and displacement of the cerebrum,

- And a gross circulatory abnormality.

While in Partial CPT, the union is of limited extent, particularly regarding its depth and only superficial surface area is affected (In which separation can be expected to follow the survival and leading a normal life for both children) (16).

O’Connell subdivided partial form on the basis of the degree of rotation of one head in relation to the other, with different abnormalities and deformities of the brain and abnormal circulation for each: (16)

- Type I vertical CPT face the same direction (in which rotation is less than 40 degrees)

- Type II CPT face opposite sides (in which rotation is between 140 and 180 degrees)

- And type III twins have an intermediate angle of rotation (in which rotation ranges from 40 to less than 140 degrees)

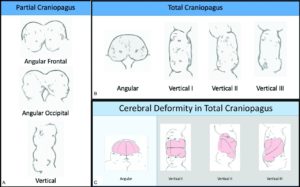

Then, Stone and Goodrich defined partial CPT as lacking substantial shared dural venous sinuses, whereas total CPT share a large portion of their dural venous sinuses and present with clear brain compression, which leads to distortion within the cranium (17). So they are in an effort to evaluate outcomes among different types of twins, used the partial and total divisions which described by O’Connell and defined 2 main subtypes based on the long-axis angle between twins: angular and vertical (4).

Angular CPT have an inter-twin longitudinal angle of less than 140 degrees, regardless of axial rotation (17)(4), while Vertical CPT display a continuous longitudinal cranium, and this type is further subdivided according to the degree of inter-twin axial facial rotation similar to the O’Connell classification (17)(2).

Figure 1: Stone and Goodrich classification for Craniopagus Twins. Partial CPT lack substantial shared dural venous sinuses. Total CPT share a large portion of dural venous sinuses and present with pronounced brain compression, leading to distortion within the cranium. The two main subtypes are based on the long-axis angle between twins: angular and vertical. Shared calvaria causes deformity of each twin’s brain. Reproduced with permission from Stone and Goodrich, 2006 (17)(2)

Surgical Separation / Operative Management

The decision to separate CPT is obviously fraught with serious and dangerous considerations, the preoperative evaluation and assessment of patients before a separation procedure is critical, and generally planning takes months of clinical monitoring, imaging, and modeling (4). Consultation among experts in multiple specialties is crucial and must involve surgeons, anesthesiologists, nursing teams, and other care providers. In addition to cranial considerations, cardiac, pulmonary, and renal function determine the feasibility of the prolonged surgical procedure of separation. Separation cannot be done until the patients have reached the age and body weight which allow them to tolerate the potentially significant blood loss that can occur during surgery (4).

The goal of surgical separation of craniopagus twins involves separating shared structures, including cerebral vasculature and interdigitating brain, and reconstructing cranial structures for each twin (2). Single and multistage approaches have been used (2).

In the single-stage procedure, one twin receives the circumferential venous sinus, while the other twin develops a deep venous drainage system through several months by serial ligation of draining veins (2). There has been limited success with this approach of separation. In general, the length of procedures often exceeds 20-30 hours (4). Unfortunately, these efforts are rarely successful because of the complexity of this procedure and the instant change in hemodynamic forces and stresses that occur when the surgeon tries to bypass the entire cerebral venous outflow. So due to the complexity of these cases and the difficulty of predicting the suitability of individual venous outflow, which must function immediately on separation, we favor or prefer a multistaged surgical approach (4).

Multistage procedures are often not required for partial CPT. Reconstruction involves adequate dural, cranial, and soft-tissue coverage (2).

The dominant twin will have a thriving and more strong clinical presentation, and the non-dominant twin may experience the effects of hypotension and low cardiac output, including oliguria, low weight, aspiration pneumonia, and failure to thrive. Most midline structures, including the circumferential venous sinus will be given to the dominant twin, with the plane of division on the side of the non-dominant twin (2).

Despite multiple previous unsuccessful attempts, the first successful separation of Craniopagus Twins occurred in 1953, only one child survived, when a multistaged approach was used (18). As techniques improved, single-stage approach became the standard for total CPT separation, in which the surviving twin received the bulk of the superior dural venous sinuses, usually surviving with severe disability, with operations often lasting as long as 22–100 hours (5)(17)(19)(20). Although surgical results for total CPT have been gradually improving through decades, single-staged results were likely no better than the earlier developed multistaged separation procedures (17).

Multistaged surgical separation is the preferred current management of choice in total CPT (21). Gradually dividing bridging veins increases collateral formation and dilation of shared or communicating veins in the non-dominant twin, who does not receive the superior sagittal sinus. This improves venous drainage, leading to decrease the risk of cerebral edema and CSF leak. Additionally, the cardiac and renal issues and number of medications needed get better by the end of the third stage (2).

Figure 2: A, Surgical-separation strategy may require sequential division of venous sinus branches from the non-dominant twin (dashed line), allowing the anatomically predisposed dominant twin to keep the CVS (black arrow) and associated dura. In the non-dominant twin, subsequent reversal of venous drainage to collateral basal channels may be induced (Reproduced, with permission, from Stone and Goodrich, 2006). B, Postcontrast MR venography demonstrates the CVS (white arrow) (17)(2).

Conclusion

Separation of Craniopagus twins must be a well-organised multidisciplinary effort. The care of these children includes critical care time, nursing, social support, travel, anesthesia, neurosurgery, diagnostic and interventional neuroradiology and the administrative support. The neuroradiologist plays a critical role in the care team of CPT, from initial evaluation through the operation and follow-up, using conventional imaging techniques CT scan, MRI, angiography, endovascular therapies and creating 3D models. Technologic advances that can greatly improve this field will include 3D virtual reality navigation to improve the knowledge of what lies behind a “wall” of fused brain in the operating room, keeping loss of brain tissue to a minimum. The combination of high-resolution MR images and virtual reality 3D systems is already in use (2). Embolizing vessels will become even more precise due to availability of new endovascular devices and embolic materials, decreasing operative time needed for vascular ligation, providing a roadmap for surgeons when they divide veins and further mitigating blood loss. Also, diagnostic and interventional neuroradiology plays an increasingly important role in the care of craniopagus twins (2).