Article Title: Whiplash – Associated Disorders

Author: Ghaleb Haj Mohammad, Omar Heih

Editors: Hamid Ghanem, Inas Jaber

Reviewer: Zain Alsaddi

Keywords: whiplash-associated disorders, cervical spine, Biomechanics, Neurovascular symptoms, Rehabilitation.

Introduction

Whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) are a term used to describe a cluster of symptoms that typically coalesce and are associated with a history of a previous neck injury resulting from sudden acceleration or deceleration, often stemming from motor vehicle accidents.1

The term “whiplash” injury was first coined by Harold Crowe in 1928 to define injuries involving the acceleration or deceleration of the cervical spine or neck region. The majority of adults with traffic injuries report pain in the neck and upper limb pain, while other common symptoms of WADs include headache, stiffness, shoulder and back pain, numbness, dizziness, sleeping difficulties, fatigue, and cognitive deficits.2,3

The injury may be acute with full recovery or may be chronic with residual long-term pain, disability, and health care resource utilization. WAD disrupts the daily lives of adults around the world and is associated with considerable pain, suffering, disability, and costs. 4,5,6

Epidemiology

More than 300 people per 100,000 are seen in emergency rooms each year in Europe and North America for whiplash injuries as a result of traffic accidents. The frequency of the condition varies between nations depending on the population, number of vehicles, traffic laws, and system of financial compensation.7,8

Biomechanics

Whiplash injuries are usually associated with Rear trauma. Studies have shown that rear-impact collisions exhibit a two-phase mechanism with complex kinematics, as opposed to the less intricate single-phase nature observed in frontal trauma. To understand the biomechanics of neck structures during a whiplash injury, many models have been used, including physical, mathematical, and animal. While there are a lot of differences between them, they demonstrate a good agreement between them.9,10

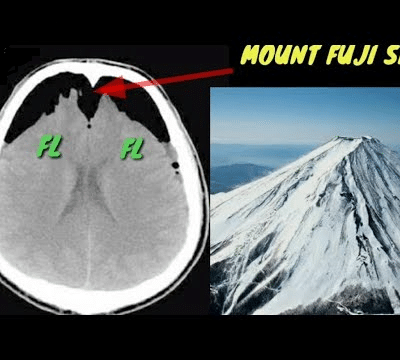

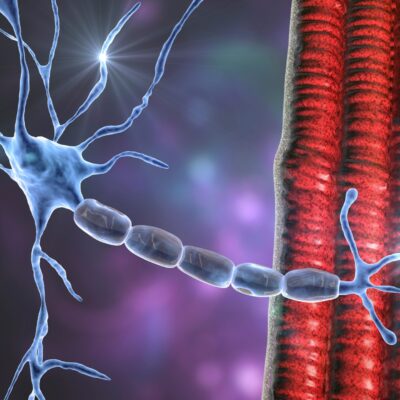

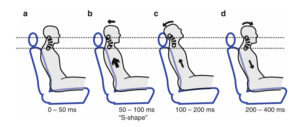

Collectively, multiple researchers have shown that the overall movement of the head and neck, which lasts 200 milliseconds during a typical rear-end vector impact, mostly stays within physiologic bounds, although aberrant motions happen within certain segments at the higher and lower cervical levels. This abnormal movement, known as the “S-shape” phase of neck motion (see FIGURE 1), can exceed physiologic limits and potentially cause sub-failure injuries to several tissues, including facet joints and capsules, the intervertebral disc, ligaments, vascular tissues, and bone structures. It consists of flexion at the upper spinal levels and extension at the lower levels.10,11

There is still evidence to suggest that neck postures or axial rotation at the moment of the collision can raise the risk of structural injury, but more quantitative “real-world” measures are probably needed to draw a firm conclusion as they do not exist yet. 11

Figure.1: The sequence of phases in whiplash injury after a collision. (a) 0–50 ms: After the impact, there is no motion or body response. (b) 50–100 ms: The torso, pushed by the seat, is pushed forward and upward; meanwhile, the head remains stationary due to the inertial force. The ascending movement of the trunk compresses the cervical spine, which, around 60 ms after the impact, undergoes an “S-shape” deformation, with the lower cervical segments exceeding physiological extension and the upper cervical segments flexion. (c) 100–200 ms: The head reaches a peak movement in extension of 45°. (d) 200–400 ms: Head, neck, and trunk start to descend, and about 400 ms after the initial impact, the head achieves its maximum forward displacement.10

Clinical features

The primary symptom of WAD is neck pain. Patients typically do not immediately report pain following trauma; instead, it often manifests hours to days later. This delayed onset is attributed to synovitis of the facet joint, resulting from non-physiological damage that restricts neck movement. The injury can affect both structural elements of the spine and neurovascular elements. In general, the pain is not lifelong and some patients recover within days to months. However, some cases reported that 20-40% of patients experience persistent neck pain lasting for several years.12,13

Besides neck pain, cervicogenic headache is the most frequent complaint and is caused by disorders of the cervical spine. Headache presents as a chronic symptom in 70% of patients. The headache’s trigger mechanism stems from inflammation or compression of the C2 nerve root. Irritation in the C2 nerve root leads to referred pain in the first branch of the trigeminal nerve.13,14

The constriction of peri-cranial muscles, which is often due to spasm or strain, will cause entrapment of the occipital nerve and lead to tension headaches. The pain is usually at the occipital region and can be exacerbated by many factors like fatigue, lack of sleep, stress, and depression. Dizziness, nausea, and vomiting which originate from the cervical spine, known as cervical vertigo, are other accompanying symptoms.12

Eye-related issues such as double vision, visual deficits, ptosis, and eye pain may emerge as a result of lesions in the oculomotor nerve, lesions in the optic nerve, sympathetic nervous system disorders, and irritation of the trigeminal nerve, respectively.15

Furthermore, numbness in the head and face, along with paresthesia around the face in an ‘onion skin’ distribution area, results from an injury to the trigeminal spinal nucleus caused by a spinal cord lesion at the level of C2-C3. Several series report instances of numbness or muscle weakness in the upper extremities due to nerve root or spinal cord lesions. Imaging studies may yield inconclusive results as there are limited laboratory tests available for these patients. 16,17

Less frequently occurring symptoms include Barré-Lieou Syndrome (headache, dizziness, and other cervical sympathetic nervous system disorders), hearing loss, ringing in the ears, insomnia, loss of concentration, memory loss, fatigability, fever, temporomandibular joint pain, angina-like chest pain (cervical angina), and dysphagia.18

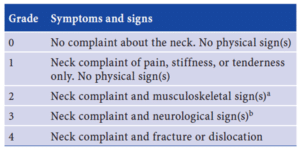

Grades of WAD are usually confined to grades 1-3 (Table 1). 19

Table 1: Clinical grading of whiplash injuries according to the Quebec Task Force of whiplash-associated disorders.

a Signs include decreased range of motion and point tenderness

b Signs include decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes, weakness, and sensory deficits. 19

Diagnosis

History taking is very important because it can rule out grades III and IV neurological symptoms, which can be an indication of nervous system and skeletal structure lesions. Whiplash injury can be split into three stages: the acute stage, which represents the first three weeks of injury; the subacute stage, when most of the symptoms disappear and the patient is still taking conservative therapy; and the chronic stage, if symptoms persist for more than three months.20

Acute whiplash injury typically includes neck, shoulder, and arm pain, headache, particularly in the occipital area radiating to the forehead, and neck stiffness. They cause limited motion in the neck. Concomitant symptoms should also be taken into consideration, and these include nausea, tinnitus, dizziness, paresthesia in the hands, visual impairments, posttraumatic stress disorder (depression), and cognitive function disorders.20

Red flags in clinical evaluation encompass various indicators, including fevers, night sweats, illicit drug use, unexplained weight loss, immunosuppression, diminished appetite, general malaise, weakness, neurologic symptoms, and a history of cancers. These factors serve as alerts during the assessment of systems. 20

Physical examination should be conducted to exclude or demonstrate nervous system damage and to pinpoint the source of pain. A neurological examination of the neck should be done, focusing on the motor function and sensibility of the arms and hands, and radicular provocation tests. Fractures should be excluded. Also, tenderness and spasms with neck pain in patients should be taken into consideration.21

Imaging plays a limited role in establishing a diagnosis, as studies are often normal unless there is notable nerve or ligamentous damage. The diagnosis of whiplash primarily relies on considering the mechanism of injury and the patient’s symptoms. For WAD I and II, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck is generally not informative, although it may be ordered in cases of suspected neurological issues. In grade VI WAD, MRI studies are seldom beneficial.22,23

MRI utility is limited but should be considered in case of neurologic abnormalities and preparation for surgical intervention. It is the gold standard for diagnosing missed or occult fractures, infections, and tumors.24

Electromyography and myelography are used in patients with persistent or chronic symptoms who need further study. Electromyography is valuable for ruling out or diagnosing lower motor neuron (LMN) lesions linked to spinal cord or nerve injuries, providing insights into the level of injury. Myelography, on the other hand, is used in cases where patients are unresponsive to non-surgical treatments, and aims to identify conditions such as disc rupture, fractures, tumors, or hemorrhages.25

A list of potential differential diagnosis that must not be overlooked includes soft tissue injury (acute neck pain, acute torticollis), fibromyalgia and psychogenic, mechanical lesions (disc prolapse, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis), inflammatory (rheumatoid, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyalgia rheumatica), metabolic (Paget’s disease, osteoporosis, gout, pseudogout), infective (osteomyelitis, TB), malignancy, and adjacent disorder (shoulder or acromioclavicular disease).26

Management

For better outcomes and cost-effective management and treatment of WAD, physicians should follow clinical guidelines closely. The approach to managing WAD varies based on the stage of the condition: early acute (0–12 weeks after injury) or chronic (over 12 weeks post-injury). The clinical course of WAD is most significant within the first 2 – 3 months after the injury, which makes it an important period for limiting the progression of the condition into a chronic one.1

The initial management involves using soft cervical collars for immobilization, in an attempt to restore normal activities and perform mobilization exercises. However, recent findings suggest that encouraging normal activity through exercises may be more effective and lead to a faster recovery without the use of neck collars. Others suggest that ultrasound therapy for muscle pain is beneficial.27,28,29

Analgesia, ice packs, heat pads, muscle relaxants, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are commonly used among first-line treatments. Moreover, biofeedback, when combined with other treatments, has proven effective for acute WAD. Also, intramuscular lidocaine injections can help with pain relief. It’s noteworthy that a combination of therapies tends to enhance overall effectiveness, compared to monotherapy regimens, with early mobilization standing out as particularly beneficial. 30,31,32,33,34

Effective management must include physiological and psychological elements because they affect WAD during its acute and chronic stages.35

Prognosis

Many factors impact the prognosis of patients suffering from WAD, including the presence of previous illnesses, the degree of WAD, age, and socioeconomic environment. The recovery period can vary, spanning from a week to several weeks or even months. Additionally, permanent disability is a potential outcome.28, 36

Conclusion

WAD is a group of symptoms that people report after experiencing a neck injury from an acceleration or deceleration of a motor vehicle accident. The prevalence of WAD varies among regions. The most frequent symptoms include neck pain, headache, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, and visual disturbances. when it comes to establishing a diagnosis, a good history can rule out grades III and IV neurological symptoms, and a physical examination can exclude or demonstrate nervous system damage. Electromyography and Myelography may be used.

Effective management of WAD is most significant within the first 2-3 months after the injury, which must include physiological and psychological elements. Recovery might take a week, some weeks, or even months. permanent disability is a possible potential outcome.