Article topic: The utilization of ketamine in managing super refractory status epilepticus

Author: Amani Alfdool

Editor: Rahmeh Adel

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Ketamine, Super-refractory status epilepticus, Status epilepticus, Anti-seizure medications.

Abbreviation: Status epilepticus (SE), Refractory Status epilepticus (RSE), Super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE), Anti-seizure medications (ASMs), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), γ-Aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA), Nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), Anit-epileptic drugs (AED).

Abstract

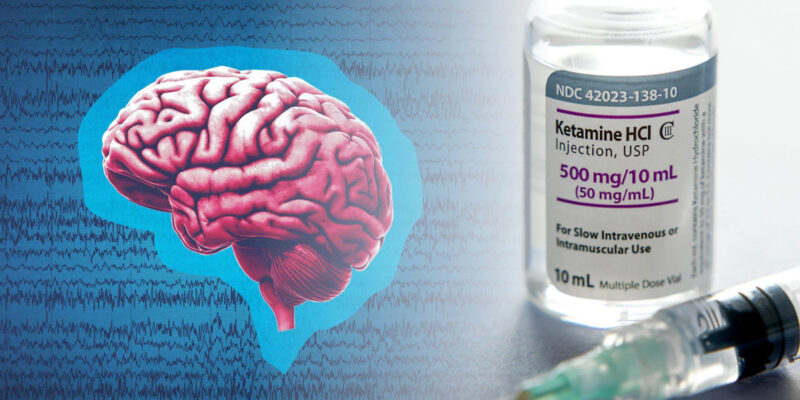

Status epilepticus (SE) is a critical neurological condition with a high morbidity and mortality. It occurs when the mechanisms responsible for ending seizures fail or when mechanisms that cause abnormally prolonged seizures are initiated. Immediate pharmacological therapy is necessary to stop seizure activity. Benzodiazepines are the first-line therapy during the initial treatment phase of SE. Midazolam, propofol, and pentobarbital are anesthetic medications used as continuous intravenous infusions in the refractory SE (RSE) period. RSE and Super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE) are life-threatening and need immediate treatment to prevent lasting brain damage and reduce the chances of death. Ketamine, an anesthetic, is being studied for its potential to stop status epilepticus (SE); however, due to the urgency and severity of the condition, there are currently no internationally recognized randomized controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of ketamine for treating super-refractory status epilepticus. The most effective pharmacological treatments for RSE and super-refractory status epilepticus are not clearly defined. Accordingly, the efficacy and safety of ketamine for terminating super-refractory status epilepticus will be discussed in this article review.

Introduction

Status epilepticus defined as “a condition coming about either from the failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure cessation or from the initiation of mechanisms which lead to abnormally prolonged seizures (after time point t1) and can have long-term consequences (after time point t2), including neuronal death, neuronal injury, and alteration of neuronal networks” by the Worldwide Association Against Epilepsy in 2015.1 This definition has two operational dimensions: the first time point (t1) represents the length of the seizure beyond which the seizure should be viewed as “continuous seizure activity.” The second time point (t2) is the time of ongoing seizure action after which there is a risk of long-term outcomes.1

Discussions exist concerning the meaning of RSE, including the number of AEDs patients need to have failed. Most specialists agree that patients should be considered in RSE after the failure of appropriately dosed starting benzodiazepine and one anti-epileptic and the length of SE after commencement of treatment. Most specialists no longer consider duration a criterion for the classification of RSE.13 Super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE) is defined as status epilepticus that continues or recurs 24 hours or more after the onset of anesthetic therapy, including those cases where status epilepticus recurs on the reduction or withdrawal of anesthesia.11

Status epilepticus is commonly caused by low anti-seizure medications (ASM) levels, cerebrovascular disease, traumatic brain injury, intracranial tumor, central nervous system infection, autoimmune encephalitis, and toxic and metabolic derangements (i.e., alcohol withdrawal/intoxication, or hypoxia).2 The excessive activation of excitatory receptors (i.e., AMPA, NMDA, glutamate, voltage-gated sodium, and calcium channels), and either downregulation, internalization, or in combination, of inhibitory receptors (i.e., GABAA receptors) are believed to be reasonable explanations for benzodiazepine resistance in SE at the cellular level.3

At diagnosis, it is essential to obtain continuous EEG.4 The glucose level, computed tomography (CT) scan of the head, and basic laboratory workup including complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and calcium level should also be obtained.5 However, 12 to 48% of SE cases turn into RSE, of which 15–22% may progress to SRSE.6,7 Focal motor seizures at onset, non-convulsive SE, high peak glucose level, and autoimmune encephalitis are risk factors for the progression from SE to RSE.8 In the majority of cases of status epilepticus (SE), continuous EEG (cEEG) and/or clinical exam will determine the persistence of SE after both emergent initial and urgent control AED treatments have been administered.5 In situations where the patient has refractory status epilepticus (RSE), it is recommended to immediately start additional agents.5

RSE and SRSE are dangerous situations that necessitate a quick start of treatment to decrease morbidity and mortality and prevent enduring neurological injury.9 RSE and SRSE as the name implies, do not respond well to commonly used anti-seizure medications (ASMs).10 It is important to be aware of the potential complications associated with the treatment of RSE and SRSE, including hemodynamic instability, propofol infusion syndrome (bradycardia, metabolic acidosis, cardiovascular collapse, rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, and hepatomegaly in the settings of high and prolonged use of propofol), ileus, acidosis, bowel perforation (with the use of high anesthetics dosages), and increased risk of infection (including pneumonia and sepsis).12

Treatment principles

The main goal of treatment is to effectively stop both clinical and electrographic seizure activity.5 The latest guidelines recommend cessation of electrographic seizures or burst suppression.13 Therefore, the treatment of status epilepticus focuses on increasing the activation of GABAA receptors. However, all current protocols take a staged approach to treatment. In the first stage of status epilepticus, benzodiazepines are used for therapy. If seizures persist, the patient enters the second stage and is treated with intravenous anti-epileptic drugs like phenytoin, phenobarbital, or valproate. If seizures continue, the patient is considered to be in the third stage, and general anesthesia is typically advised to achieve EEG burst suppression.11

Different first-line ASMs for treating resistant SE were compared in a large randomized, controlled, comparative-effectiveness, the Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT). The trial showed that seizure cessation rates were similar (50%) for patients treated with fosphenytoin (20 mg/kg phenytoin equivalents max 1500 mg), levetiracetam (60 mg/kg max 4500 mg), or valproic acid (40 mg/kg max 300 mg). No significant differences were observed in side effects such as hypotension, arrhythmias, or respiratory depression requiring endotracheal intubation, except that fosphenytoin was associated with higher rates of hypotension and endotracheal intubation compared to levetiracetam and valproic acid.14 Additional medications examined in case studies are topiramate, perampanel, brivaracetam, lacosamide, and phenobarbital. Phenobarbital was given by mouth and helped in the successful withdrawal of pentobarbital.15–19

Although drugs acting at the GABAA receptor can control brief status epilepticus, they are less effective in prolonged status epilepticus. According to a co-operative study conducted by the Veterans Administration, less than 25% of patients with prolonged (5.4 h) subtle status epilepticus were controlled by phenobarbital, lorazepam, diazepam, and phenytoin or phenytoin.20 General anesthesia is often used to treat refractory status epilepticus, but it can be costly and has the potential to cause low blood pressure and infection. Data on the most effective anesthetics for RSE and SRSE is limited, but benzodiazepines, propofol, and barbiturates are often utilized. Midazolam and propofol have been the top choices for continuous anesthetics for RSE and SRSE for a long time.21 This indicates the necessity for a new type of anticonvulsant to treat status epilepticus that does not respond to GABAergic drugs. Ketamine, a clinically available N-methyl D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, has been tested to control status epilepticus refractory to GABAergic drugs.22

Ketamine is a phencyclidine analog that acts as a nonspecific antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor.23 Ketamine works by binding to the allosteric benzene clonidine (PCP) site within the ionizing channel pore of the NMDA receptor, usually administered in a single anesthetic dose.24 A systematic review reported the use of ketamine for RSE with loading doses ranging from 0.5 to 5 mg/kg and continuous infusion rates from 1 to 10 mg/kg/h.25

The time between the seizure onset and ketamine administration was found to be important for predicting how well ketamine would work. In an animal study looking at prolonged seizures, ketamine was most effective when given at least one hour after the seizure started.22 Ketamine was given after 24 h in most of the cases in many studies. In a study by Sabharwal et al., where it was used as a primary or secondary anesthetic, the seizure resolution rate was 91%.26 But, when ketamine was used as a third-choice anesthetic agent in one case series, seizure resolution rate was found to be only 40%.10 In a study by Gaspard et al., 31% of patients who received ketamine within a median of 4.5 days (6 h to 30 days) after SE onset, showed a possible or likely response. The rest, in which ketamine was administered within a median of 10 days (12 h to 122 days) did not show any response.27

Accordingly, we can infer that the administration of ketamine earlier (as a first/second-line anesthetic agent) after SRSE diagnosis has better efficacy.10 Ketamine can cause both tachycardia and bradycardia, hypertension and hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, hypersalivation, metabolic acidosis, and an emergence phenomenon upon termination.28 Although case reports and case series previously reported a link between ketamine use and increased intracranial pressure, two large systematic reviews have disproved this association. It’s important to mention that these reviews specifically looked at bolus dosing in the operating room, not the high-dose continuous infusions used for SRSE.29,30 However, no mortality was linked directly to the dose and duration of ketamine use. Rather, mortality was found to be positively correlated with older age, longer duration of RSE, and Nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) in some previous studies.31,32,33

In general, ketamine was found to be safe and effective in most of the studies leading to termination of prolonged seizures. Even if complete resolution was not achieved, using ketamine still helped reduce seizure frequency in patients with SRSE. SRSE with treatable causes was found to have better outcomes. Also, in most of the studies, early treatment with ketamine was associated with improved seizure control outcomes.

Conclusion

Super-refractory status epilepticus is a severe condition. The mortality rate is high, ranging from 30 to 50% in different studies. However, there is a significant lack of published data on the effectiveness, safety, and outcome of many therapies and treatment approaches, despite it being an important clinical problem.

Ketamine seems to be safe and effective for the management of SRSE, leading to resolution in many patients and a significant reduction in seizure frequency in most others. Early administration of ketamine is associated with better outcomes, while mortality rates are more dependent on baseline age and seizure duration rather than ketamine dosage or duration.

References