Article Title: Spinal cord infarction

Author : Mahmoud Mohammed Hamed Abukhashab

Editor: Dr Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords : Spinal cord injury; Myelopathies; Vascular disorder

Overview and Epidemiology

Myelopathy is a term that refers to a pathology leading to a neurologic deficit related to the spinal cord [1], Spinal cord infarction is a rare but an aggressive disorder caused by a wide range of pathologic states. Patients usually present with acute paraparesis or quadriparesis, depending on the spinal cord level that is involved. The diagnosis is often made clinically with neuroimaging studies to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other conditions. Spinal cord infarction accounts for 1%-2% of all ischemic strokes and 5%-8% of all acute myelopathies [2]. The total occurrence rate of stroke in the United States ranges from 540,000 to 780,000 per year, it is expected that 5000 to 8000 cases of spontaneous spinal cord infarction occur each year [3,4]. These figures may be underestimated, as they likely do not include spinal cord infarction complicating major surgery, which is the most common cause of spinal cord infarction. Spinal cord infarction occurs usually in adults and, the mean age is 64 years; this is expected, as it is a complication of atherosclerotic vascular disease [5]. However, children and neonates in specific circumstances can develop spinal cord infarction [6]. Patients at risk may include those having operations between T6 and L2, open surgical repair, acute aortic dissection, prior abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery, elderly, vascular risk factors; some of the associated risks include hypertension [7], smoking, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus [8], and the presence of aortic atheroma [9].

Vascular anatomy of spinal cord

There are three major vessels arising from the vertebral arteries in the neck and supply the spinal cord [10]. One anterior spinal artery (ASA) and two of posterior spinal arteries (PSAs) (Fig. 1). The ASA from its name supplies the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord. The ASA and PSAs anastomose at the conus medullaris [11]. The spinal arteries receive their blood supply from other regional arteries: C1-T3 is supplied by the vertebral arteries, T3-T7 receives a branch from the intercostal arteries, T8 to the medullary conus is supplied by the Adamkiewicz artery [11]. The artery of Adamkiewicz is the largest of these and typically arises from T9 to T12 and supplies the lumbar enlargement of the spinal cord, (Fig. 2). The watershed area in the middle to upper thoracic cord is unproven, therefore; the majority of cases are due to hypoperfusion that occur in the lower thoracic cord [13,14].

Figure1; spinal cord vascular anatomy. Neuropedia.net

Figure2; Origins of the vessels supplying the spinal cord from the aorta at various vertebral levels. Neuropedia.net

Pathogenesis and Etiology

There will be a restriction of blood flow to spinal cord white matter or grey matter. This will lead to insufficient delivery of oxygen and glucose, leading to a metabolic failure of affected spinal cord tissue. The etiologies of infarction include atherosclerosis, aortic dissection, infection, systemic hypo- tension, emboli, vasculitis, decompression sickness and coagulopathy [14].

Clinical presentation and complications

Generally, spinal cord infarction presents with typical sudden onset of pain, weakness; flaccid initially with absent reflexes and/or loss of sensation; most commonly at level T10 [14,15]. Typically upper motor neuron signs will develop, but if there is a significant involvement of anterior horn cell it may not develop. In approximately one-third of patients, there will often be a radicular and may be transient back or neck pain that localizes to the level of infarction [16]. The sudden onset of symptoms that is associated with pain may mimic angina or myocardial infarction [17]. In a more broad way, clinical presentation depends mainly on the location and extent of the infarction. As we said before there are ASA and PSAs that supplies the spinal cord, so any abruption of blood flow to these arteries will lead to some syndromes that well be discussed.

Anterior spinal artery syndrome [18] which is the most common clinical presentation of spinal cord infarction, there will be a loss of motor function and pain/temperature sensation bilaterally, the vibration and proprioception sensation below the level of the lesion is usually spared. The acute stages of syndrome are characterized by flaccid paralysis and loss of deep tendon reflexes; After days and weeks spasticity and hyperreflexia may develop. We will also have autonomic dysfunction that may be present as hypotension (either orthostatic or frank hypotension), sexual dysfunction, and/or fecal and urinray incontinence. We may have respiratory failure if the lesion is in the rostral (toward the head) cervical cord. Ischemia is sometimes localized to the level of the anterior horns and that is what we called Incomplete Syndrome of the Spinal Artery Syndrome [18], the presentation in this case will be:

1) Acute paraplegia (pseudopoliomyelitic form) without loss of sensation or sphincter dysfunction.

2) Painful bilateral brachial diplegia “stiffness, weakness, or lack of mobility in muscle groups” in the case of a cervical lesion (the man-in-the-barrel syndrome) [19].

3) chronic lesions of the anterior horns will lead to progressive distal amyotrophy and this form may be misdiagnosed as lateral amyotrophic sclerosis.

Moving to Posterior Spinal Artery Syndrome [18]. The manifestation will be loss of vibration and proprioception sensation below the level of the injury (The opposite of what we mentioned about ASA syndrome) and total anesthesia at the level of the injury. Typically, the weakness is mild and transient. Involvement is unilateral which is more common, but bilateral presentations have also been described [15].

Workup and diagnosis

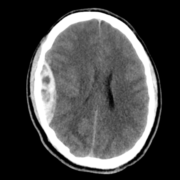

As we said the diagnosis is often made clinically with neuroimaging studies that include Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomogram (CT). MRI is the imaging modality of choice in a case where we suspect spinal cord ischemia, but unfortunately it may appear entirely normal in up to 24% of acutely symptomatic patients [8]. In the MRI protocol we should do both sagittal and axial T1 and T2-weighted sequences, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), post-contrast imaging [20]. DWI MRI is sensitive for detecting cord ischemia and it shows a characteristic high signal indicating that there is a cytotoxic edema and reduced free water diffusivity [21]. Now to support the diagnosis of spinal cord ischemia, we have some characteristic MRI “signs”; sagittal T2-weighted MRI may show a pencil-like (Fig. 3) zone of signal abnormality, while sagittal T1-weighted image may show a focal elevation signal that represent hemorrhagic transformation, or can show a segmental cord swelling [20,21] (Fig. 4, B). If the watershed zone of the gray matter of the anterior horns is affected, then the classic “owl’s eyes” or “snake eyes” sign can develop on T2 axial MRI [22,23,24] (Fig. 3). We can also do a Lumbar Puncture which is not helpful in the initial workup but the CSF may show elevation in protein concentration which is nonspecific [8,15].

Figure 3 T2-weighted MRI images. The axial slice shows a snake eye-lesion that suggest spinal cord infarction.

Figure 4 T1-weighted MRI images. The sagittal slice shows pencil-like signal hyperintensity [25]

Treatment and management

If ischemia was left untreated it will become progressive and worsen over the first few hours [26]. The primary mechanism i.e. hypotension/hypoperfusion, embolism; will reach the plateau by 24 h after that the secondary mechanism will be more dominant [27], so we should highlight the importance of the treatment in acute phase “the first 24 h” in reversing the primary mechanism and decrease the damage from the secondary mechanism.

As a conclusion, early resuscitation and supportive measures will help us minimize the spinal cord damage from the secondary pathophysiological mechanisms and may improve quality of life in patients with long-term outcome [28].

Ischemia Secondary to Embolism, Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator was reported in many patients. One patient was quickly diagnosed, made a noticeable recovery and was discharged with almost no deficits after 72 h [29]. Three other cases were reported, three injections of streptokinase and steroids were given over 1-week interval. All three patients recovered with no or minimal neurological deficits [30]. The main barrier to such managements is time, as there are contraindications to using thrombolytic therapy [31] and excluding these, the time of diagnosis may also be beyond the optimal therapeutic windows.

Ischemia Secondary to hypotension/hypoperfusion, it can be a part of both primary mechanisms due to myocardial infarction and internal hemorrhage or part of secondary mechanism of cord damage. To reverse the neurological deficits in spinal cord ischemia that happen after aortic surgery and thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), specific management guidelines have been set [32]. If the patient awakes from anesthesia with neurological deficit, the chance to reverse this pathology will be low, rather than the findings developing after a period of normal neurological function postoperatively [28].

The Role of High-Dose Steroids shows a benefit following acute spinal trauma in patients with complete and incomplete spinal cord injuries if it was administrated within 3 rather than 3–8-h window [28]. microvascular perfusion and spinal cord blood flow may be improved by high-dose of steroids [33, 34] as well as clinical neurologic recovery after experimental spinal cord injury [35].

Surgical Decompression, the timing and the efficacy of early decompression (within 24 h) in improving neurologic recovery are still a matter of discussion [36,37]. Studies of early decompression from 1966 through 2000 [38] showed that surgery performed within 24 h will have a significant improvement in neurologic recovery compared with late surgery, but the outcome shows that the evidence was not strong and that early surgery could be considered only as a practice option.

Risk factors

We mentioned some of the risk factors in this article and to summarize them:

- Aortic surgery; surgical repair of thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections are the most common etiology for SCI [39, 40, 5].

- Atherosclerosis of segmental arteries.

- Abdominal/pelvic surgeries.

- Hypertension [7].

- Smoking, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus [8].

- Fibrocartilaginous embolism.

- Hypercoagulable conditions [41, 42].

- Spinal angiomas.

- Radiation injury [43, 44].

- Vasculitis [43, 44].

- Epidural anesthesia [39, 40, 45].

- Substance abuse (e.g., cocaine) [46].

- Drug induced (e.g., sildenafil citrate) [47].

- Old age.

Prevention and Prognosis

As a preventive measurement, the key for spinal thrombolysis is early diagnosis. Early resuscitation measures to improve the local perfusion and decrease secondary cord damage may extend the current 3-h therapeutic window for intra-arterial thrombolysis [28]. The metabolism of spinal cord, neurotoxic neurotransmitters level and free radicals along with inflammatory mediators can be decreased by pharmacologic agents. However, in preventing spinal cord injury there is no single technique that has proved consistently to be safe and effective. But a combination of distal aortic perfusion and pharmacologic interventions that attenuate ischemic and reperfusion injury represent the most accepted methods in prevention [48]. The poor prognosis with permanent and disabling consequence is what the spinal cord infarction (SCI) carries. Therefore, the mortality rate of SCI based on published case series ranges from 9 % to 23 % [49, 5, 50, 51]. High risk mortality rate associated with cardiac arrest, aortic rupture or dissection, and high cervical involvement [50]. Respiratory complications are the leading cause of death among acute phase survivors [52]. Secondary complications are typically chills, pressure sores, urinary sepsis, atelectasis, pneumonia, and deep vein thrombosis [53]. Joint contractures and heterotopic calcification may be present as a result of prolonged immobilization [52].

References

- Oyinkan Marquis B, Capone PM. Myelopathy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;136:1015-1026. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53486-6.00052-1

- Finsterer J, Löscher W, Quasthoff S, et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegias with autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, or maternal trait of inheritance. J Neurol Sci 2012;318(1–2):1–18. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.025.

- Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, et al. How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology 2007; 68:326.

- Williams GR. Incidence and characteristics of total stroke in the United States. BMC Neurol 2001; 1:2.

- Robertson CE, Brown RD Jr, Wijdicks EFM, Rabinstein AA (2012) Recovery after spinal cord infarcts: long-term outcome in 115 patients. Neurology 78(2):114–121. doi:10.1212/ WNL.0b013e31823efc93

- Spencer SP, Brock TD, Matthews RR, Stevens WK. Three unique presentations of atraumatic spinal cord infarction in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2014; 30:354.

- Lynch DR, Dawson TM, Raps EC, Galetta SL. Risk factors for the neurologic complications associated with aortic aneurysms. Arch Neurol. 1992 Mar;49(3):284-8.

- Zalewski NL, Rabinstein AA, Krecke KN, Brown RD, Wijdicks EFM, Weinshenker BG, Kaufmann TJ, Morris JM, Aksamit AJ, Bartleson JD, Lanzino G, Blessing MM, Flanagan EP. Characteristics of Spontaneous Spinal Cord Infarction and Proposed Diagnostic Criteria. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 01;76(1):56-63

- Kramer CL. Vascular Disorders of the Spinal Cord. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2018;24(2, Spinal Cord Disorders):407-426. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000595

- Prasad S, Price RS, Kranick SM, et al. Clinical reasoning: a 59-year-old woman with acute paraplegia. Neurology 2007; 69:E41.

- Hurst RW. Spinal vascular disorders. In: Resonance Imaging of the Brain and Spine, 2nd ed, Atlas SW (Ed), Lippincott, Philadelphia 2006. p.1387.

- Romi F, Naess H: Characteristics of spinal cord stroke in clinical neurology. Eur Neurol 2011;66:305-309.

- Korse NS, Pijpers JA, van Zwet E, et al. Cauda equina syndrome: presentation, outcome, and predictors with focus onmicturition, defecation, and sexual dysfunction. Eur Spine J 2017;26(3): 894–904. doi:10.1007/s00586-017-4943-8.

- Fairbank J, Hashimoto R, Dailey A, et al. Does patient history and physical examination predict MRI proven cauda equina syndrome? Evid Based SpineCare J 2011;2(4):27–33. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1274754.

- Novy J, Carruzzo A, Maeder P, Bogousslavsky J. Spinal cord ischemia: clinical and imaging patterns, pathogenesis, and outcomes in 27 patients. Arch Neurol. 2006 Aug;63(8):1113-20.

- Gleave JR,Macfalane R. Cauda equina syndrome: what is the relationship between timing of surgery and outcome? Br J Neurosurg 2002;16(4): 325–328. doi:10.1080/0268869021000032887.

- Harringan M, Deveikis J: Handbook of Cerebrovascular Disease and Neurointerventional Technique, (ed 2), Springer Science, Business Media, New York: Humana Press, 2013

- Vargas MI, Gariani J, Sztajzel R, et al. Spinal cord ischemia: practical imaging tips, pearls, and pitfalls. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(5):825-830. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A4118

- Berg D, Mullges W, Koltzenburg M, et al. Man-in-the-barrel syndrome caused by cervical spinal cord infarction. Acta Neurol Scand 1998;97:417–19

- Vargas MI, Gariani J, Sztajzel R, Barnaure-Nachbar I, Delattre BM, Lovblad KO, Dietemann JL. Spinal cord ischemia: practical imaging tips, pearls, and pitfalls. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015 May;36(5):825-30.

- Weidauer S, Nichtweiß M, Hattingen E, Berkefeld J. Spinal cord ischemia: aetiology, clinical syndromes and imaging features. Neuroradiology. 2015 Mar;57(3):241-57.

- Bosmia AN, Hogan E, Loukas M, et al: Blood supply to the human spinal cord: part I. Anatomy and hemodynamics. Clin Anat 28(1):52-64, 2015.

- Ross Jeffrey S, Moore Kevin R: Diagnostic Imaging: Spine. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys Inc, 2004

- Mawad ME, Rivera V, Crawford S, et al: Spinal cord ischemia after resection of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol

- Martínez Tébar MJ, Baeza Román A, Julia Mejia Olmos G. “Snake eye” and “pencil-like” signs together with diaphragmatic paralysis in a patient with anterior spinal cord ischemia. Med Intensiva (English Ed. 2019;43(7):452. doi:10.1016/j.medine.2019.06.004

- Fehlings MG, Tator CH, Linden RD (1989) The effect of nimodipine and dextran on axonal function and blood flow following experimental spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg 71(3):403–416. doi:10.3171/ jns.1989.71.3.0403

- Tator CH (1991) Review of experimental spinal cord injury with emphasis on the local and systemic circulatory effects. Neurochirurgie 37(5):291–302

- Boddu SR, Cianfoni A, Kim KW, et al. Spinal Cord Infarction and Differential Diagnosis.; 2016. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-9029-6_30

- Restrepo L, Wityk RJ, Grega MA et al (2002) Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the brain before and after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Stroke 33(12):2909–2915.

- Baba H, Tomita K, Kawagishi T, Imura S (1993) Anterior spinal artery syndrome. Int Orthop 17(6):353–356

- Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr et al (2013) Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association. Stroke 44(3):870–947. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a

- McGarvey ML, Cheung AT, Szeto W, Messe SR (2007) Management of neurologic complications of thoracic aortic surgery. J Clin Neurophysiol 24(4):336–343. doi:10.1097/ WNP.0b013e31811ec0b0

- Young W, Flamm ES (1982) Effect of high-dose corticosteroid therapy on blood flow, evoked potentials, and extracellular calcium in experimental spinal injury. J Neurosurg 57(5):667–673. doi:10.3171/jns.1982.57.5.0667

- Anderson DK, Means ED,Waters TR, Green ES (1982) Microvascular perfusion and metabolism in injured spinal cord after methylprednisolone treatment. J Neurosurg 56(1):106–113. doi:10.3171/ jns.1982.56.1.0106

- Anderson DK, Saunders RD, Demediuk P et al (1985) Lipid hydrolysis and peroxidation in injured spinal cord: partial protection with methylprednisolone or vitamin E and selenium. Cent Nerv Syst Trauma 2(4):257–267

- Fehlings MG, Tator CH (1999) An evidence-based review of decompressive surgery in acute spinal cord injury: rationale, indications, and timing based on experimental and clinical studies. J Neurosurg 91(1 Suppl):1–11

- Fehlings MG, Perrin RG (2005) The role and timing of early decompression for cervical spinal cord injury: update with a review of recent clinical evidence. Injury 36(Suppl 2):B13–B26. doi:10.1016/ j.injury.2005.06.011

- La Rosa G, Conti A, Cardali S, Cacciola F, Tomasello F (2004) Does early decompression improve neurological outcome of spinal cord injured patients? Appraisal of the literature using a metaanalytical approach. Spinal Cord 42(9):503–512. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101627

- Sandson TA, Friedman JH (1989) Spinal cord infarction. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 68(5):282–292

- Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, Howard JF Jr (1996) Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology 47(2):321–330. doi:10.1212/WNL.47.2.321

- Rothman SM, Nelson JS (1980) Spinal cord infarction in a patient with sickle cell anemia. Neurology 30(10):1072–1076

- Von Pohle WR (1996) Disseminated mucormycosis presenting with lower extremity weakness. Eur Respir J 9(8):1751–1753

- Whiteley AM, Hauw JJ, Escourolle R (1979) A pathological survey of 41 cases of acute intrinsic spinal cord disease. J Neurol Sci 42(2):229–242

- Gibb WR, Urry PA, Lees AJ (1985) Giant cell arteritis with spinal cord infarction and basilar artery thrombosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 48(9):945–948

- Sliwa JA, Maclean IC (1992) Ischemic myelopathy: a review of spinal vasculature and related clinical syndromes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 73(4):365–372

- Sawaya GR, Kaminski MJ (1990) Spinal cord infarction after cocaine use. South Med J 83(5):601–602

- Walden JE, Castillo M (2012) Sildenafil-induced cervical spinal cord infarction. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 33(3):E32–E33. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2628

- Mauney, M. C., Blackbourne, L. H., Langenburg, S. E., Buchanan, S. A., Kron, I. L., & Tribble, C. G. (1995). Prevention of spinal cord injury after repair of the thoracic or thoracoabdominal aorta. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 59(1), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4975(94)00815-O

- Nedeltchev K, Loher TJ, Stepper F et al (2004) Long-term outcome of acute spinal cord ischemia syndrome. Stroke 35(2):560–565. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000111598.78198.EC

- Salvador de la Barrera S, Barca-Buyo A, Montoto-Marqués A, Ferreiro-Velasco ME, Cidoncha- Dans M, Rodriguez-Sotillo A (2001) Spinal cord infarction: prognosis and recovery in a series of 36 patients. Spinal Cord 39(10):520–525. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101201

- Masson C, Leys D, Meder JF, Dousset V, Pruvo JP (2004) Spinal cord ischemia. J Neuroradiol 31(1):35–46

- DeVivo MJ, Kartus PL, Stover SL, Rutt RD, Fine PR (1989) Cause of death for patients with spinal cord injuries. Arch Intern Med 149(8):1761–1766

- Aharon-Peretz J, Adir Y, Gordon CR, Kol S, Gal N, Melamed Y (1993) Spinal cord decompression sickness in sport diving. Arch Neurol 50(7):753–756