Title of article: CIDP (Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy)

Author: Mohammad J. Al-Soudi.

Editors: Haneen Al-Abdallat, Haneen A. Banihani

Reviewer: Dr. Hala Qaryouti

Keywords: Demyelinating, neuropathy, autoimmune, weakness, ataxia.

Overview

CIDP (Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy) is an acquired heterogeneous autoimmune disease of the peripheral nervous system characterized by progressive weakness and impaired sensory function in the arms and legs, causing motor weakness as well as sensory symptoms and signs. Manifestations of the disease predominantly involve large, myelinated fibers, producing muscle weakness and sensory ataxia.

The disease was first described and given the name “chronic inflammatory polyradiculopathy” by Peter J. Dyck in 1975 (1), to which the term “demyelinating” was later added. Over the past years, elucidating novel aspects of the immunopathogenesis of the disease has seen significant progress.

Epidemiology

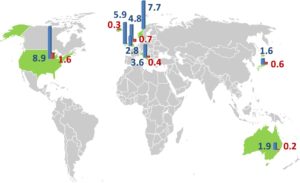

The reported prevalence of CIDP is greatly variable, ranging from 1.9 per 100,000 in some studies to 7.7 per 100,000 in others. In the United States (US), the annual incidence of CIDP was estimated at 1.6 per 100,000 people, while the prevalence was at 8.9 per 100,000 people. (2)

It has been reported that prevalence differs according to geographical distribution, as shown in figure (1) below, but the reason is still unknown. Besides methodological differences, actual geographical differences as described for other autoimmune disorders or differently applied diagnostic criteria are potential explanations.

Figure (1): Epidemiology of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: an overview of prevalence (per 100 000/year, blue) and incidence (per 100 000/year, red) in different geographical regions in the world (9)

Risk Factors

CIDP can occur in anyone. Certain dietary habits impact the risk of CIDP and that antecedent infections may influence the onset and clinical presentation of the disease (23).

Interestingly, a preliminary study seems to indicate that some dietary habits (i.e., eating rice three or more times/ week or eating fish at least once/ week) decreased the risk of acquiring CIDP. In addition, antecedent infections may impact the onset and clinical presentation of the disease. (23)

Etiology and Pathogenesis

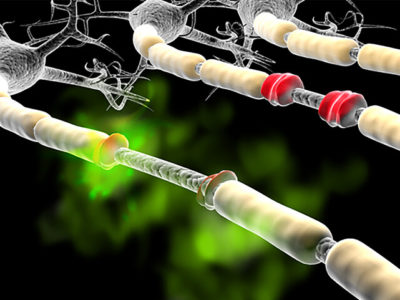

CIDP is mediated by the autoimmune destruction of myelin surrounding large peripheral nerve fibers through cellular and humoral immunity (figure 2), leading to demyelination that presents as weakness, numbness, paresthesia, and sensory ataxia. As the disease progresses, axonal loss occurs secondary to demyelination. (4)

The disease is displayed by two phenotypes; typical and atypical, which may or may not share the same pathogenesis (5). Autoantibodies identified so far include vinculin, LM1, neurofascin-155, neurofascin-186, gliomedin, and contactin-1 (6,7,8).

Figure (2): Pathogenesis of CIDP. (25)

CIDP is usually classified as follows:

1- Progressive: The disease continues to worsen over time.

2- Recurrent: Episodes of symptoms that recur and remit.

3- Monophasic: One bout of the disease that lasts 1-3 years and does not recur.

Clinical Presentation and Complications

CIDP comes with insidious, recurrent, and progressive symptoms with a clinical course showing a demyelinating process that persists for more than eight weeks. The “relapsing-remitting ” course of CIDP can be displayed in about a third of patients (10). The symmetrical motor weakness affects the proximal or distal muscles with a predominance of large-fiber neuropathy paresthesias in comparison with small-fiber neuropathies.

Typical CIDP is the most common subtype and accounts for at least 50- 60% of all cases (11,12). Multiple variants of CIDP are distinguished according to their clinical presentation and/or pathogenic mechanism. Forms of CIDP are recognized as variants by the European Academy of Neurology (EAN), and the Peripheral Nerve Society (PNS) criteria, including [13]:

- Multifocal CIDP.

- Focal CIDP.

- Motor CIDP.

- Sensory CIDP.

- Distal CIDP

Diagnosis

The initial diagnosis of CIDP relies on the signs and symptoms, but the definitive diagnosis is through evidence of peripheral nerve demyelination, identified by either electrodiagnostic testing or nerve biopsy. (15)

All patients with suspected CIDP are recommended to do electrodiagnostic testing, and the diagnosis should be considered in any patient with progressive symmetrical or asymmetrical polyradiculopathy that is either relapsing-remitting or progressive for more than two months. (15)

The EFNS/PNS Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnostic criteria for CIDP developed by the EFNS/PNS (European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society) are the most commonly used (14). This set of criteria involves the following:

- History and neurologic examination

- Electrodiagnostic testing

- Laboratory studies, which include:

-

- Fasting serum glucose and/or oral glucose tolerance test

- Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C)

- Serum calcium and creatinine

- Complete blood count

- Liver function tests

- Thyroid function studies

- Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation

- Serum-free light chain (FLC) assay, or 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP) and immunofixation.

Additional testing can include neuroimaging, nerve biopsy, and nerve ultrasound.

The EAN/PNS Diagnostic Criteria

Another set of criteria that may be used for diagnosis is those of the EAN/PNS. The EAN/PNS guideline defines CIDP as a typical (i.e., classic) or variant form [13]. The diagnosis is based on clinical, electrodiagnostic (mandatory), and supportive criteria.

The EAN/PNS clinical inclusion criteria for typical CIDP include the presence of a progressive, stepwise, or recurrent symmetric proximal and distal weakness and the involvement of sensory dysfunction in at least two limbs, developing over two months or longer, with absent or reduced tendon reflexes in all extremities.

The Koski Diagnostic Criteria

The Koski criteria were derived by predictive modeling of the clinical data of 150 patients diagnosed with CIDP or other polyneuropathies by expert consensus (16).

To diagnose idiopathic CIDP, the Koski criteria require the following:

• Chronic polyneuropathy, progressive for at least eight weeks without serum paraprotein nor any genetic abnormalities,

and either:

• Recordable compound motor action potential (CMAP) in at least 75% of motor nerves with:

- either abnormal distal latency or abnormal motor conduction velocity n >50% of motor nerves, or

- abnormal F wave latency in >50% of motor nerves,

OR

• Symmetric onset/ exam, with weakness in all 4 limbs, at least one of which has a proximal weakness.

Management and Treatment

Treatment of patients with CIDP is complex and requires individualized treatment strategies. First-line therapies that have been shown to be effective include corticosteroids, IVIg, and plasma exchange (17 – 19).

It is assumed that IVIg exerts anti-inflammatory activity in autoimmune neuropathies by several mechanisms of action, including Fc-dependent and Fab-dependent mechanisms, such as neutralization of autoantibodies, inhibition and abrogation of activated complement, alteration of FcR expression, and redressing altered cytokine patterns (20).

Nowadays, the standard treatment regimen with IVIg in CIDP is an induction dose of 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 consecutive days, and a maintenance dose of 1.0 g/kg IV every 3 weeks. This treatment has been shown effective when CIDP patients were followed up over 24 weeks and have yielded high response rates (almost 70%) after 52 weeks of maintenance on the regimen. (21)

With respect to corticosteroids, a retrospective study compared different regimens (including daily oral prednisolone, pulsed oral dexamethasone, or pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone) in 125 patients with CIDP. Results showed a 60% response rate to corticosteroids, with no significant difference in safety and efficacy between the three treatment regimens (22).

Prognosis

In an experiment, the long-term prognosis of CIDP patients was generally favorable. However, 39% of patients still required immune treatments, and 13% had severe disabilities. Mode of onset, distribution of symptoms, and electrophysiological characteristics may hold prognostic value for favorable outcomes. (24)

Recent Updates

Around the world, many studies are currently exploring ways to get more out of our current CIDP treatments. These studies include the ProCID and DRIP studies, mainly conducted in Europe, which will aid us in understanding the way IVIg dose and administration frequency influence efficacy. In the Netherlands, an ongoing IOC trial will help us understand how often remission occurs in CIDP.

The GRIPPER study conducted in the US may shed insight into how CIDP symptoms fluctuate between IVIG infusions. Each of these studies anticipates a conclusion in 2018 or 2019. Accordingly, they will inform us on how to personalize IVIG treatment: how to get more out of the treatment for patients in need and how to get these patients off treatment if it is no longer needed.

Looking further out, the OPTIC trial conducted in the Netherlands and UK will explore the role of combining IVIG treatment with corticosteroids. This trial is expected to wind up in 2023.

References...