Article Title: Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease (CMT)

Author: Yara Alswaiti

Editor: Leen Adayleh

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Introduction

Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease is a group of inherited disorders that affect the peripheral nerves, leading to problems with movement and sensation. It is one of the most common inherited neurological disorders, with various subtypes and genetic causes. Understanding the genetics, clinical features, diagnosis, and management of CMT is crucial for proper patient care and the development of future treatments. In this comprehensive article, we will explore the various aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease to provide a deeper understanding of this condition and the latest advancements in its management and potential therapies.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease (CMT) is synonymous with the term hereditary motor sensory neuropathy (HMSN). CMT encompasses a range of disorders resulting from genetic mutations in different genes, leading to abnormalities in proteins expressed in myelin, gap junctions, and/or axonal structures found in peripheral nerves.1

CMT is classified into main categories: CMT types 1 through 7 and the X-linked category, CMTX. Each category is further subdivided, associating a specific gene with a particular disease, such as CMT1A, CMT1B, etc. The genetic landscape of CMT is diverse, with many identified causative genes up to the present.1

Epidemiology

Genetic epidemiology is essential in understanding Charcot–Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease stands as the most prevalent inherited disorder affecting the peripheral nervous system, with an estimated occurrence of 1 in 1214 individuals. CMT1 and CMT2 exhibit comparable frequencies within the general population. The prevalence rates for PMP22 duplication and mutations in Cx32, MPZ, and MFN2 are reported as 19.6%, 4.8%, 1.1%, and 3.2%, respectively.2

The overall prevalence in the entire age population was 17.69 per 100,000 (95% CI 12.32-24.33), with a notably higher prevalence for CMT1 at 10.61 per 100,000 (95% CI 7.06-14.64) compared to other subtypes (P’ < 0.001). Although not statistically significant, the prevalence appeared to be greater in individuals aged 16 or 18 years and above (21.02 per 100,000) compared to those aged below 16 years (16.13 per 100,000). 3

Genetic Basis

While it is important to recognize the genetic basis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT), it’s also crucial to consider its multifactorial nature. While genetic factors play a significant role in the development of CMT, environmental factors and lifestyle choices can also influence its progression and severity. Therefore, focusing solely on the genetic aspect may lead to overlooking other important factors that contribute to CMT’s overall management and treatment.

CMT is linked to over 80 distinct genes. Identifying the precise genetic factor underlying CMT hereditary neuropathy can be valuable for discussions related to prognosis and for genetic counseling purposes.4

The majority of individuals identified with autosomal dominant CMT inherit the disorder from an affected parent. However, there are instances where individuals diagnosed with autosomal dominant CMT acquire the condition due to a de novo pathogenic variant. The proportion of cases resulting from a de novo pathogenic variant varies based on the specific gene involved. In some cases, the family history of individuals diagnosed with autosomal dominant CMT may appear negative due to factors such as a failure to recognize the disorder in family members, the early demise of a parent before the onset of symptoms, or the late onset of the disease in the affected parent.4

In autosomal recessive CMT cases, the affected individual’s parents are obligate heterozygotes, meaning they carry one pathogenic variant. These heterozygotes, or carriers, do not exhibit symptoms and are not susceptible to developing the disorder.4

Understanding the interplay between genetics, environment, and lifestyle factors can provide a more comprehensive approach to managing CMT. By considering a broader range of influences, healthcare professionals can develop personalized treatment plans that address all aspects of the disease, leading to improved patient outcomes.

Clinical Features

To further understand the clinical features and symptomatology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, it is essential to recognize the diverse range of symptoms that can manifest in individuals with this condition. The most common symptoms of CMT include muscle weakness, foot deformities, loss of sensation, and difficulty with balance and coordination. These symptoms can vary in severity and may progress differently among affected individuals.

Additionally, individuals with CMT may also experience secondary complications such as musculoskeletal issues, fatigue, and chronic pain, which can significantly impact their quality of life.

It is essential for healthcare professionals to be aware of the wide spectrum of symptoms associated with CMT to diagnose and manage the condition accurately. Moving forward, a comprehensive approach that considers both CMT’s genetic and clinical aspects will be integral in developing tailored treatment strategies and advancing potential therapies for individuals affected by this disease.

Types of CMT

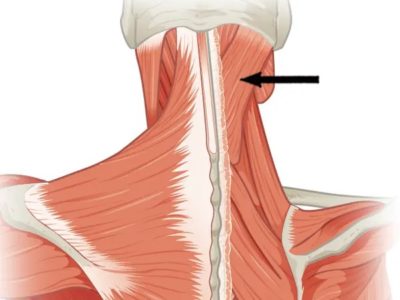

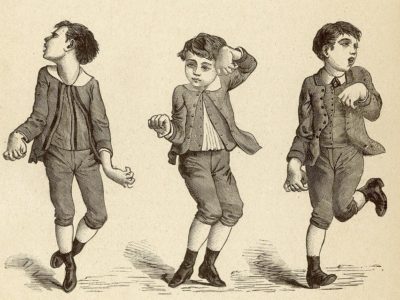

CMT1 is a condition characterized by the demyelination of peripheral nerves and follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. CMT1A, attributed to the duplication of the PMP22 gene, constitutes approximately 70 to 80 percent of CMT1 cases. Infants carrying this pathogenic variant may exhibit symptoms, often categorized as congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy or Dejerine-Sottas disease. Initial complaints might involve recurrent ankle sprains due to distal muscle weakness or challenges in running and keeping pace with peers. Clinical examinations may reveal areflexia, pes cavus, weakness, and atrophy in the distal lower extremities. Notably, distal calf muscle atrophy may lead to the characteristic “stork leg deformity,” which tends to become more pronounced with the progression of the disease. Walking becomes awkward due to both muscle weakness and sensory loss. Sensory loss gradually advances, which is detectable by a decline in proprioception and vibration sense on physical examination. Later stages may witness atrophy in the intrinsic hand and foot muscles. Peripheral nerves might show palpable enlargement due to hypertrophy.5

CMT2 is characterized by predominant axonal damage and follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. It is less prevalent than CMT1, as evidenced by reduced motor amplitudes observed in nerve conduction studies and indications of chronic reinnervation on needle electromyography (EMG). Distal weakness, atrophy, sensory loss, diminished deep tendon reflexes, and variable foot deformity constitute the typical clinical manifestations of CMT2. Symptoms typically occur in the second or third decade of life, slightly later than in CMT1. While the clinical course resembles CMT1, CMT2 may exhibit more prominent sensory symptoms, characterized by the loss of vibration and proprioception and lack of palpable enlargement of peripheral nerves. Late-onset forms of CMT2 have been documented, presenting between 35 to 85 years of age. Autosomal dominant pathogenic variants primarily account for CMT2 cases, although autosomal recessive inheritance is possible. However, the genetic basis of CMT2 remains incompletely understood.6

CMT X-linked comprises a set of inherited disorders affecting peripheral nerves arising from gene mutations on the X chromosome. Various subtypes exist within CMT X-linked, including CMTX1, CMTX2, CMTX3, CMTX4, and CMTX5. CMTX1, the second most prevalent form following CMT1A, is linked to pathogenic variants in the gap junction protein beta 1 (GJB1) gene. Manifesting more prominently and initiating earlier in males, CMTX1 typically presents with gait issues, foot deformities, and sensory loss, often becoming apparent in infancy or later in childhood. CMTX2, an X-linked recessive form mapped to Xp22, is notable for its infantile onset, featuring atrophy and weakness in lower leg muscles, areflexia, and pes cavus. CMTX3, also X-linked recessive, is associated with a 78 kb insertion at chromosome Xq27.1, originating from chromosome 8. CMTX4 represents a rare infantile-onset axonal X-linked CMT attributed to pathogenic variants in the apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 1 (AIFM1) gene. CMTX5, an X-linked recessive disorder involving deafness and optic neuropathy, has been reported in a Korean family and is caused by pathogenic variants in the phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase 1 (PRPS1) gene.7

CMT3 encompasses two severe early-onset peripheral neuropathies: Dejerine-Sottas syndrome and congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy. These conditions are characterized by the incapacity of Schwann cells to generate normal myelin, resulting in the formation of thin, inadequately developed myelin. Dejerine-Sottas syndrome manifests in early infancy with hypotonia and exhibits delayed motor development, pronounced sensory loss, distal weakness followed by proximal weakness, absent reflexes, ataxia, and a significant reduction in nerve conduction velocities. The condition may lead to scoliosis and contractures, with a gradual progression that often allows ambulation to be maintained into adulthood. Congenital hypomyelination neuropathy is marked by the absence of myelin without indications of inflammation, myelin breakdown, or onion bulbs. The genetic origins of these conditions exhibit considerable overlap, leading to a diminishing distinction between the two diseases.8

CMT4 denotes a set of infrequent demyelinating motor-sensory neuropathies following an autosomal recessive pattern, presenting clinically with greater severity compared to autosomal dominant forms. Individuals with CMT4 typically display the characteristic CMT phenotype involving distal muscle weakness and atrophy, accompanied by sensory loss and foot deformities. The conduction velocities in CMT4 tend to be slow, and the condition is less likely to arise from pathogenic variants in structural myelin proteins in comparison to autosomal dominant forms. CMT4 is further subdivided into various subtypes, such as CMT4A, CMT4B, CMT4C, CMT4D, CMT4E, and CMT4F. Each subtype is characterized by specific genetic mutations and exhibits distinct clinical features, including variations in age of onset, severity of symptoms, and overall clinical presentation.9

Diagnostic Criteria and Procedures for Charcot-Marie-Tooth

Diagnosing CMT begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination to rule out conditions distinct from CMT, as outlined in this overview. These exclusions encompass systemic disorders featuring neuropathy, various hereditary neuropathies, distal myopathies, hereditary sensory neuropathies (HSN), and hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies (HSAN), as well as acquired disorders. In cases where CMT is confirmed, detailed family history and the application of molecular genetic testing become crucial for identifying a specific genetic cause.

Beginning with gathering a three-generation family history and focusing on relatives displaying neurological signs and symptoms. Subsequently, conduct a thorough Molecular Genetic Test, with the initial step recommending PMP22 deletion/duplication analysis for all individuals with CMT. In the second step, utilize a multigene panel encompassing the eight most frequently implicated genes (GDAP1, GJB1, HINT1, MFN2, MPZ, PMP22, SH3CT2, and SORD) to pinpoint the genetic origin of the neuropathy likely. This approach helps minimize the identification of variants with uncertain significance and pathogenic variants in genes that do not explain the observed phenotype. If a genetic cause remains elusive after Steps 1 and 2, consider Step 3, which involves comprehensive genomic testing. This advanced testing, where the clinician doesn’t need to predetermine the likely involved gene(s), may include exome sequencing as the more common approach, with genome sequencing also being a viable option.4

Once a CMT-related pathogenic variant has been identified in an affected family member, it becomes feasible to conduct predictive testing for at-risk relatives. However, engaging in formal genetic counseling before testing is crucial to discuss potential outcomes, including socioeconomic changes and the necessity for long-term follow-up and evaluation arrangements for individuals with positive test results. The discussion should encompass the capabilities and limitations of predictive testing. In cases involving asymptomatic minors at risk for adult-onset conditions where early treatment offers no significant benefits to disease morbidity and mortality, predictive genetic testing is considered inappropriate. This is primarily because it undermines the child’s autonomy without providing a compelling advantage.4

Current Management Strategies for Charcot-Marie-Tooth

Currently, there is no successful pharmaceutical intervention accessible for the treatment of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT). The optimal care for individuals with inherited neuropathies involves a comprehensive approach led by a multidisciplinary team of experts. This team typically includes genetic counselors, physical and occupational therapists, nurses, neurologists, orthopedic surgeons, and physiatrists. This diverse group reflects the various aspects of care essential for addressing the complex needs of these patients. 10

The development of the rehabilitation plan should center not only on addressing particular symptoms that impact the quality of life and daily activities but also on preventing complications, mainly falls and joint deformities. Orthotic devices, such as ankle-foot orthoses, are frequently employed to stabilize the ankles and improve walking function. Surgical interventions by orthopedic foot specialists may be advantageous for severe cases of pes cavus deformity and hammer toes, usually performed in adolescence or early adulthood.10

The Future of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Management

As research in genetics and neurology continues to advance, there is growing interest in exploring potential future treatments for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Understanding the condition’s complex genetic underpinnings has led to the identification of potential therapeutic targets that could pave the way for novel treatment approaches.

One area of emerging interest is gene therapy, which holds promise for addressing the root genetic cause of CMT. By targeting specific genetic mutations associated with the disease, gene therapy aims to correct or mitigate the effects of these mutations, potentially offering a transformative treatment option for individuals with CMT.

Furthermore, advancements in neuroregeneration and neuroprotection have sparked optimism for potential disease-modifying treatments. Therapeutic interventions aimed at promoting nerve regeneration, protecting nerve cells from degeneration, and modulating the underlying disease processes are being actively researched for their potential to alter the course of CMT and improve patient outcomes.

Neurotrophin-3 (NT3) demonstrated enhanced axonal regeneration and concurrent myelination in both a xenograft model featuring Schwann cells with a PMP22 duplication and in a mouse model harboring a pathogenic PMP22 single-nucleotide variant (SNV). Furthermore, a single-blinded pilot clinical trial involving eight patients with CMT1A, outlined in the same report, revealed that NT3 treatment over six months was linked to improved regeneration of myelinated fibers in the sural nerve compared to those receiving a placebo.11

In addition to exploring disease-modifying treatments, ongoing investigation into symptomatic management strategies to address the diverse clinical manifestations of CMT is underway. This includes the development of assistive devices, rehabilitative therapies, and multidisciplinary care approaches aimed at optimizing the functional abilities and quality of life of individuals with CMT.

Emerging therapeutic approaches involve the use of a progesterone antagonist in a Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT-1A) model. Application of the selective progesterone receptor antagonist demonstrated a reduction in the overexpression of Pmp22 and enhancement of the CMT phenotype in wild-type or transgenic rats, with no apparent adverse effects. These findings collectively support the concept that targeting the progesterone receptor in myelin-forming Schwann cells holds promise as a pharmacological intervention for treating CMT-1A.

The outcomes in an animal model aligned with these observations, indicating that the introduction of progesterone led to a more advanced neuropathy. 12

In an animal model of CMT1A, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), known for its ability to support myelination, showed promise. In mice treated with ascorbic acid, all subjects either halted the decline in locomotor performance (as assessed by rotarod tests) or demonstrated enhanced performance within the initial month of treatment (based on beam-walking and grip tests). This improvement persisted throughout the entire treatment period. The findings imply that the administration of high doses of ascorbic acid resulted in the correction of the neuropathic phenotype in the transgenic mouse model.13

The following is a compilation of medications identified as posing moderate to significant risks for individuals with CMT. The list includes Amiodarone, Bortezomib, Cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, Colchicine (extended use), Dapsone, Dichloroacetate, Disulfiram, Gold salts, Leflunomide, Metronidazole/misonidazole (extended use), Nitrofurantoin, Nitrous oxide (inhalation abuse or vitamin B12 deficiency), Perhexiline (not used in the United States), Pyridoxine (high dose), Stavudine, Suramin, Tacrolimus, Taxol (paclitaxel, docetaxel), Thalidomide, and Zalcitabine. These medications carry potential risks and should be approached with caution in individuals with CMT.14

Advancements in Genetic Treatments for Charcot-Marie-ToothTop of Form

The exploration and investigation of gene therapies for inherited conditions falling under the umbrella term Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) have been ongoing since the molecular-genetic causes started becoming apparent. Only recently have these discussions translated into clinical feasibility with the rapid advancements in gene therapy tools and their applications for various neuromuscular and neurological disorders. Despite significant progress in proof-of-concept studies, multiple challenges persist. Additionally, the diverse disease mechanisms associated with different CMT types may also necessitate distinct gene therapy approaches.

Therapies should be directed towards the primary cell type affected, such as motor and sensory neurons in axonal neuropathies and Schwann cells in demyelinating neuropathies.

In a published study on CMT gene therapy, rodents were employed as preclinical models. These models were chosen due to their capacity to mimic diverse molecular and pathological features of Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) neuropathies. This selection aimed to accurately replicate various phenotypes and stages of severity associated with the disease for testing potential gene therapy approaches. The difficulties and constraints in evaluating gene therapies for CMTs in rodent models encompass factors such as variations in nerve length and body weight between rodents and humans. Additionally, the careful selection of suitable models is essential to accurately represent diverse phenotypes and stages of severity in CMT neuropathies.15

Conclusion

As the understanding of CMT continues to evolve, collaborative efforts between researchers, healthcare providers, and individuals living with the condition will be essential for translating scientific advancements into tangible therapeutic options. By embracing a comprehensive approach that integrates genetic insights, clinical considerations, and innovative treatment modalities, there is hope for a future where individuals affected by CMT can benefit from more personalized and effective treatments.

References...