Article Topic: Lyme Disease

Author: Reem Muhsen

Editors: Sadeen Eid, Odette El Ghawi

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Lyme disease, B. burgdorferi, ticks, Lyme neuroborreliosis

Overview

Lyme disease (LD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed zoonotic tick-borne diseases worldwide [1]. Human cases have risen since the etiological agent, Borrelia burgdorferi, was first recognized [1]. Often referred to as the “last great imitator,” Lyme disease is notable for its wide range of clinical manifestations [2]. Lyme disease typically occurs in woodland areas with moderate climates, particularly in mid to late summer [3]. This seasonal prevalence correlates with the Ixodes tick’s life cycle, the disease’s primary vector. Although Lyme disease is commonly associated with dermatological symptoms, it is considered a multisystem disease. The nervous system is the second most frequently affected after the skin [3]. Neuroborreliosis, characterized by symptoms such as meningitis, radiculopathy, and encephalopathy, can arise as a disease complication. Other systemic complications associated with Lyme disease include uveitis, carditis, keratitis, and inflammatory arthritis; however, these complications are less frequently reported in European cases of Lyme disease [3].

Etiology

Lyme disease is an infectious disease caused by spirochete bacteria belonging to the Borrelia genus. The most common species responsible for Lyme disease in North America is Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (s.s.), while B. garinii and B. afzelii are also significant pathogens, particularly in Asia [4]. Humans are considered incidental hosts, meaning that they are not the primary targets of the bacteria but can become infected through specific exposures.

Transmission and Lifecycle of Ticks

The transmission of Lyme disease primarily occurs through the bites of infected ticks, particularly during their nymph stage, which is most commonly associated with human infection. While nymph bites are the usual mode of transmission, bites from adult ticks can also lead to infection, albeit less frequently. Each stage of the tick’s life cycle involves one blood meal, during which the ticks can acquire the infection [3]. Other potential vectors, such as fleas and mosquitoes, have been investigated, but ticks are the primary transmitters of Lyme disease [5].

Pathogenesis of Lyme Disease

The pathogenesis of Lyme disease is not yet fully understood. However, the accumulation of immune complexes in the arachnoid villi is believed to play a role in the disease’s underlying mechanisms [6]. The spirochetes can spread to the nervous system through the bloodstream [7]. Alternatively, they may migrate from the site of entry along peripheral nerves to reach the nerve roots, meninges, and subarachnoid space [7]. This ability to infiltrate the nervous system contributes to the neurological manifestations often seen in Lyme disease.

Clinical Presentation

Early Localized Infection-Stage 1

Erythema migrans is a typical rash associated with Lyme disease. In this stage, it appears as a target-like lesion, with localized erythema spreading out from the site of inoculation as demonstrated in Figure 1 [3,12]. Approximately 50% of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) report no rash, likely because the primary infection occurs in an inaccessible area or below the hairline [3]. One-quarter of patients with neuroborreliosis recall having tick bites, and about half report a localized skin reaction [8]. The rash during this stage typically presents as a homogeneous, erythematous, annular lesion [9].

Figure 1: Erythema Marginatum [12]

Early Disseminated Infection-Stage 2

Symptoms usually occur within several days to weeks after contact with an infected tick [9]. Signs include multiple (secondary) erythema migrans lesions, along with musculoskeletal, neurologic, or cardiovascular symptoms [9]. Neurologic symptoms, such as meningitis, paralysis of the seventh cranial nerve, and radicular neuropathies, occur in approximately 15% of patients [9].

Late Disseminated Infection-Stage 3

Present in sixty percent of untreated cases, Lyme disease can manifest with variable pain and swelling in one or more joints [10]. Periodically, neurological manifestations may develop, including chronic polyneuropathy or encephalopathy [9]. Encephalopathy is associated with symptoms such as insomnia, malaise, impaired mentation, and sometimes personality changes [9]. If left untreated, Lyme disease can cause substantial disability, though it is rarely fatal [9].

Peripheral nervous system (PNS) involvement is usually sensory, and it can be either patchy or diffuse, with paresthesia or hypoesthesia being the main symptoms [11]. The neuropathy typically depends on the topographical distribution of the skin disease, although unaffected extremities may also show signs of neuropathy [11].

Neurological complications

In Europe and the United States, early central nervous system (CNS) involvement is characterized by three manifestations, which may occur alone or in combination: lymphocytic meningitis, cranial neuritis, and radiculoneuritis [13]. Over 95% of patients present within six months of infection and any neurological complications during this period are considered early neuroborreliosis [3].

Optic Nerve Involvement

Optic neuropathy occurs rarely in Lyme disease [14]. Optic nerve involvement in Lyme neuroborreliosis often goes unnoticed but can lead to significant morbidity [11]. However, cases of retrobulbar optic neuritis, neuroretinitis, papillitis, and ischemic optic neuropathy have been reported in association with Lyme disease [11]. Papilledema may occur due to elevated intracranial pressure in Lyme meningitis, particularly in children and some adults [11].

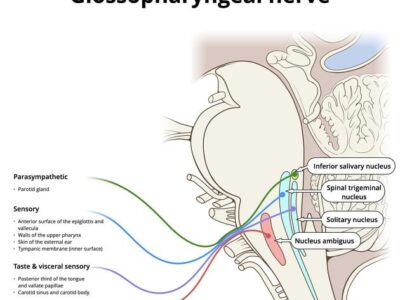

Facial Nerve and Vestibulocochlear Nerve Involvement

The most frequent presentation of early Lyme neuroborreliosis in the U.S. is facial palsy [15]. Facial weakness begins acutely, usually during the summer season [15]. The facial nerve is the most affected cranial nerve [16]. However, Lyme disease can also impact the eighth cranial nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve), leading to deafness, as well as cranial nerves responsible for eye movement, which can cause diplopia [16]. Approximately one-third of patients will also exhibit cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis [17]. Other cranial nerves are less likely to be affected [15].

It is possible to misdiagnose patients with early Lyme neuroborreliosis and facial palsy as having Bell’s palsy [15]. Systemic manifestations of Lyme neuroborreliosis may include headache, radicular pain, and presentation at the end of summer or fall, along with a history of tick bite or erythema migrans [15]. In endemic regions, screening for Lyme disease and occult meningitis should be conducted in children with facial nerve palsy [18].

Meningitis

Clinical symptoms of meningitis are variable, ranging from those that are hardly distinguishable from viral meningitis (with significant temporal overlap) to asymptomatic pleocytosis identified during the evaluation of cranial neuropathy or radiculopathy [13]. An important point in distinguishing Lyme meningitis from viral meningitis is the increased risk of intracranial pressure and papilledema associated with Lyme meningitis [19]. Meningitis primarily occurs in young adults, with a predominance in male patients. Initial symptoms typically include headache, myalgia, and fever [20].

Mononeuritis, Polyneuritis

In Lyme neuroborreliosis, detecting Positive borrelia serology, with peroneal nerve plexitis, mononeuritis multiplex, symmetrical polyneuritis, and mononeuritis might occur [20].

Bannwarth Syndrome

Bannwarth syndrome is a frequent neurologic complication of Lyme disease in Europe due to peripheral nerve inflammation [21]. A common manifestation of early LNB is subacute painful meningoradiculitis (Bannwarth syndrome) [7]. Symptoms include the usual combination of painful radiculitis, and peripheral motor deficits, accompanied by lymphocytic CSF inflammation [7].

Diagnosis

Patients’ clinical scenarios play a crucial role in the diagnosis of Lyme disease [9]. Doctors treat patients based on their clinical manifestations [9]. Typical laboratory tests are often not very helpful in diagnosis, as the white blood cell (WBC) count can be normal or elevated [9]. Results for hemoglobin, hematocrit, creatinine, and urinalysis are usually within normal limits [9]. In cases involving the nervous system, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples may show the presence of lymphocytes, elevated protein concentration, and positive oligoclonal bands, while glucose concentration remains normal [22].

Serologic tests for Lyme disease can assist in diagnosis but are not always essential [9]. These tests are susceptible to false-negative and false-positive results, as antibodies to B. burgdorferi may not be detectable during the early course of the disease, which can lead to misleading conclusions [9]. When confirmation is needed, the CDC recommends using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which is sensitive but not necessarily specific, followed by the Western blot test [9]. Ordering Western blot tests should be considered when the results from the ELISA or indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) tests are indeterminate [9].

Risk Factors

Climate change is likely to affect the distribution and abundance of ticks, thereby influencing the incidence of Lyme disease [23]. Additionally, a person’s place of residence has been identified as a risk factor [24]. Ticks are sensitive to environmental conditions, as they require a minimum relative humidity of 80 percent to prevent fatal desiccation during their prolonged nonparasitic phases [23].

In regions where decreased summer precipitation coincides with increased summer temperatures, ticks’ survival, activity, and distribution are likely to decline due to their vulnerability to desiccation [25]. Landscape factors, such as the presence of forests, also contribute to the risk of Lyme disease [26]. Furthermore, forest fragmentation may increase contact rates between the human population and ticks, leading to a higher incidence of the disease [27].

Treatment

Early Infection

The main treatment for an early infection is oral doxycycline [28]. Other options, such as amoxicillin and cefuroxime, are available in cases where doxycycline is contraindicated [28]. However, macrolides are considered a last resort for patient management [28].

For patients presenting with active central nervous system disease (such as meningitis or acute radiculopathy) and significant neurological findings, treatment involves a 14 to 28-day course of intravenous ceftriaxone [28].

Late Infection

Patients with late stages, including inflammatory arthritis, should be treated with Doxycycline orally (or any other oral alternative) for 4 to 8 weeks [28]. Supporting treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be helpful [28].

Pregnant women and children

Pregnant women and children should be treated based on the stage of the disease.

For children older than eight years, doxycycline can be administered orally. In those aged eight or younger, amoxicillin is the preferred oral medication, with cefuroxime or erythromycin as alternative options.

Doxycycline is contraindicated during pregnancy; therefore, oral alternatives such as amoxicillin and cefuroxime can be used [28].

Prevention

Personal Protective Measures

Individuals at serious risk of exposure should take protective measures to minimize the risk of tick bites and infection with pathogens [29]. These measures include bathing after activities in endemic areas and wearing protective clothing [30].

Repellents to Avoid Tick Bites

To prevent tick bites, several repellents are highly recommended, including N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET), picaridin, ethyl-3-(N-n-butyl-N-acetyl) amino propionate (IR3535), oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), p-menthane-3,8-diol (PMD), 2-undecanone, and permethrin [29].

Removing Attached Ticks

Attached ticks can be removed using mechanical methods, such as a clean, thin-tipped tweezer (or any similar device) applied between the tick’s body and the skin. Alternatively, burning an attached tick with a heating device or exposing the tick to poisonous chemicals, such as petroleum products, can aid in detaching it [29].

For chemoprophylaxis, a single dose of doxycycline is recommended within three days (72 hours) of removing the tick. The recommended dosage is 200 mg for adults and 4.4 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 200 mg) for children [29].

Risk Factors

Climate change is likely to affect the distribution and abundance of ticks, thereby influencing the incidence of Lyme disease [23]. Additionally, a person’s place of residence has been identified as a risk factor [24].

Ticks are sensitive to environmental conditions, as they require a minimum relative humidity of 80 percent to prevent fatal desiccation during their prolonged nonparasitic phases [23]. In regions where decreased summer precipitation coincides with increased summer temperatures, ticks’ survival, activity, and distribution are likely to decline due to their vulnerability to desiccation [25].

Landscape factors, such as the presence of forests, also contribute to the risk of Lyme disease [26]. Furthermore, forest fragmentation may increase contact rates between the human population and ticks, leading to a higher incidence of the disease [27].

Prognosis

Most patients diagnosed with Lyme disease are cured within 3 to 4 weeks with an antibiotic course [31]. However, a minority of patients (about ten percent) experience prolonged neurocognitive and somatic symptoms, such as insomnia, myalgia, arthralgia, memory impairment, fatigue, and headache [32]. This condition is referred to as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS) or post-Lyme disease syndrome (PLDS) [33].

Conclusion

Lyme disease is one of the most commonly diagnosed zoonotic tick-borne diseases, with a worldwide distribution. The incidence, presentation, and clinical manifestations of Lyme disease vary depending on the stage of the illness, as it is a multistage and multisystem disease. Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) refers to neurologic involvement resulting from systemic infection by the spirochete bacteria Borrelia.

Several neurological manifestations may occur after the initial infection, including facial palsy, which is considered the most frequent presentation of early Lyme neuroborreliosis, as it primarily affects the facial nerve. Other cranial nerves, such as the vestibulocochlear nerve and the optic nerve, may also be affected, contributing to significant morbidity. Meningitis can occur with a wide range of clinical symptoms, in addition to mono-neuritis, polyneuritis, and many other neurological complications.

Diagnosing patients is based on their clinical manifestations; however, ordering an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) followed by the Western blot test is recommended to confirm the diagnosis. Regarding early and late infection therapy, doxycycline is typically the treatment of choice unless contraindicated. Regardless of the clinical presentation, most manifestations and symptoms of Lyme disease will resolve when treated with appropriate antimicrobials. Persistent symptoms after treatment are most often due to post-Lyme disease syndrome (PLDS).

References...

Good lecture

Thank you for this effort. Wishing all of you all the success.