Article topic: Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Authors: Aline Safa, Joyce Labaky

Editors: Odette El Ghawi, Joseph Akiki

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, brain imaging, vasogenic edema

Abstract

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome is increasingly recognized and is characterized by the acute onset of vasogenic edema, notably in the posterior fossa. It often presents following an acute precipitating factor such as hypertension, pre-eclampsia, shock, or immunosuppression. Clinically, it manifests primarily as headache, visual impairment, and seizures. The pathogenesis is poorly understood, but vascular leakage or endothelial injury may explain the syndrome. Management typically involves addressing the underlying cause and, in most cases, admission to the ICU. Recent studies suggest that the use of vaptans and targeting brain-blood barrier dysfunction may lead to positive outcomes.

Introduction

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), also known as posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome, is a radiological and clinical entity first described in Paris and Boston in 1996. It is a rare and poorly understood syndrome characterized by cerebral vasogenic edema in the white matter of the occipital and temporal lobes.

PRES symptoms mainly include seizures, visual impairment, and headache. It may less frequently present with limb weakness and confusion. These symptoms usually appear acutely [1]. PRES appears at the onset of acute moderate to severe hypertension, pre-eclampsia, auto-immune disease, renal disease, infection, immunosuppressant drugs, and chemotherapy [2]. Its diagnosis has become easier with improved imaging techniques, specifically Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Acute hypertension is the most predictive risk factor for PRES; however, it is still unclear why certain patients develop PRES while others do not [1].

The term posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) can be somewhat misleading, as it may lead to irreversible cerebral injury in a minority of cases [3]. Additionally, the vasogenic edema associated with PRES can have an atypical distribution, affecting regions beyond the posterior fossa, such as the frontal lobe, basal ganglia, brainstem, or cerebellum [4]. Moreover, despite its name, not all patients with PRES exhibit encephalopathy, further contributing to the complexity of its presentation.

Epidemiology

PRES is increasingly recognized due to notable advances in brain imaging and expanded awareness. However, it remains underdiagnosed because of diagnostic challenges and numerous differential diagnoses.

According to a study by the American Heart Association, PRES accounts for approximately 0.03% of hospitalizations. It can affect patients across all age ranges, but it is more prevalent among middle-aged women, with a mean age of around 45 [5].

Etiology and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis behind the PRES is not fully understood and is still debated. There are two main theories retained.

Vascular Leakage Theory

The first theory proposes that a sudden increase in blood pressure can result in cerebral hyperperfusion, disrupting the cerebrovascular autoregulation mechanism of the blood-brain barrier. This disruption leads to vascular leakage and the development of vasogenic edema [6].

Notably, the posterior circulation is predominantly affected due to its relatively poor sympathetic innervation. This explains why the edema tends to preferentially involve the occipital and parietal lobes [2].

Endothelial Dysfunction

The second theory emerged after studies showed that more than 30% of patients with PRES did not have hypertension [6]. This theory suggests that endothelial damage occurs due to exposure to toxins. These toxins can be either endogenous, as in cases of sepsis and pre-eclampsia, or exogenous, such as from chemotherapy and immunosuppressive drugs.

According to this theory, hypertension results from endothelial damage, which triggers the release of vasoactive substances and pro-inflammatory cytokines. This also increases vascular permeability, leading to vasogenic edema [7].

Clinical presentation and complications

PRES typically has a rapidly progressive onset, often evolving within a few hours [8].

Approximately 70% of patients with PRES present with acute hypertension, with systolic blood pressure ranging between 170 mmHg and 190 mmHg [9].

Common symptoms at presentation include seizures, visual impairment, and headache. Less frequently, patients may exhibit focal neurological signs, confusion, nausea, and vomiting. These symptoms can manifest in various forms, and the clinical severity can vary significantly. For instance, while some patients may experience mild confusion, others may present in a comatose state. Visual impairment can range from blurry vision to complete cortical blindness.

Workup and Diagnosis

PRES is diagnosed based on both clinical and radiological findings. Since symptoms and clinical signs are often non-specific, imaging plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis.

The gold standard for diagnosing PRES is brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), as it provides higher resolution and more detailed visualization of brain structures, especially in the posterior fossa, compared to CT scanning [10]. However, given that many patients present acutely, CT scanning is often used initially for its rapid assessment capabilities and can still confirm the diagnosis in most cases.

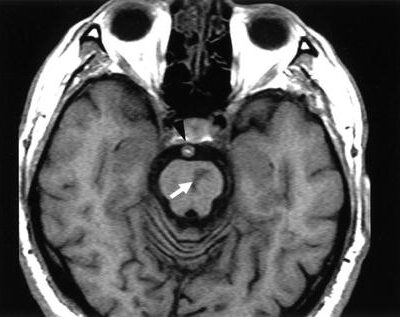

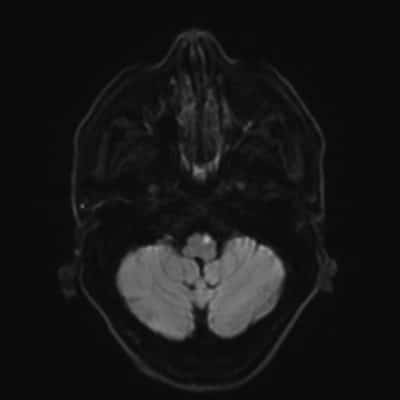

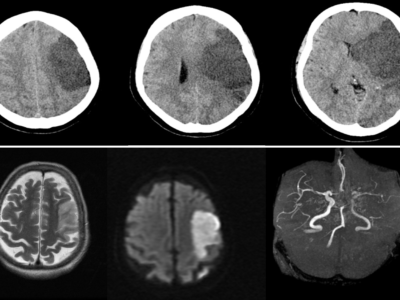

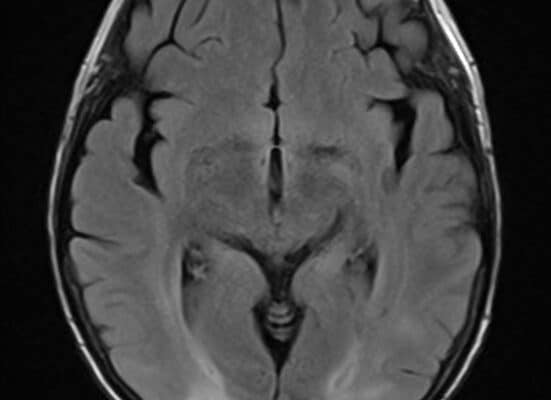

On brain MRI, the characteristic findings of PRES include vasogenic edema, which appears as high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and increased ADC values. The edema typically follows one of three patterns: holo-hemispheric, parieto-occipital, or superior frontal sulcus, with brainstem edema appearing rarely [11]. Although the edema is usually symmetric, it may occasionally present asymmetrically.

Figure 1 shows abnormalities involving predominantly the subcortical white-matter in both parietal and occipital lobes in a relatively symmetrical fashion, corresponding to increased T2/FLAIR signal in a patient diagnosed with PRES [11].

![Increased T2/FLAIR signal in both parietal and occipital lobes in a relatively symmetrical fashion corresponds showing vasogenic edema relative to PRES [11].](https://neuropedia.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/10-262x300.jpeg)

Figure 1: MRI brain showed increased T2/FLAIR signal in both parietal and occipital lobes showing vasogenic edema in PRES [11].

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for PRES. Management primarily focuses on treating or reversing the underlying cause, which often leads to the resolution of vasogenic edema. For instance, blood pressure control is crucial, and it is typically recommended to reduce blood pressure by 20–25% in hypertensive patients [10]. In cases related to renal failure, dialysis may be necessary, while in patients with preeclampsia or eclampsia, induction of labor is often required to resolve the condition.

Despite these interventions, approximately 70% of patients may still require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) for symptomatic management. This includes addressing encephalopathy, controlling seizures, ensuring airway protection, and stabilizing the patient’s overall condition [13]. In the ICU, antiepileptic drugs may be administered for seizure control, and close monitoring of neurological and hemodynamic status is essential.

Prognosis

PRES was originally characterized as a benign, reversible condition with favorable outcomes. Approximately 80% of cases fully recover within a few days to weeks.

Nevertheless, mortality has been observed in 19% of patients, and functional impairments such as epilepsy and motor deficits have been reported in 44% [14,15]. As an acute neurotoxic syndrome, the prognosis of PRES largely depends on the underlying cause. Factors associated with poor outcomes include severe encephalopathy, hypertensive etiology, hyperglycemia, neoplastic causes, multiple comorbidities, elevated CRP levels, low CSF glucose, and coagulopathy [14-17].

Recent updates

Recent updates on the management and understanding of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) highlight advances in both pathophysiological insights and therapeutic strategies.

According to the vascular leakage theory, PRES is characterized by excessive blood flow that disrupts the blood-brain barrier (BBB), leading to increased vascular permeability and subsequent brain edema [18]. This theory underscores the importance of targeting BBB disruption in future therapeutic approaches, which could potentially offer more effective treatment options by addressing the root cause of the edema.

Recent research has also explored the role of arginine vasopressin in the pathology of PRES. Studies suggest that suppression of arginine vasopressin, a hormone involved in fluid balance and vascular tone, may be beneficial in managing PRES. The use of vaptans, a class of medications that antagonize vasopressin receptors, has shown promise in modulating the effects of arginine vasopressin and improving outcomes in PRES patients [19]. These findings indicate a potential new avenue for treatment, focusing on the hormonal regulation of vascular permeability and fluid balance as part of the management strategy for PRES.

References...