Article Topic: Giant cell arteritis

Author: Omar Alkhateeb

Editors: Zaid Shakhatra, Sadeen Eid.

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Temporal arteritis, Vasculitis, Headache, Autoimmune disease, Polymyalgia rheumatica

Overview

Giant cell arteritis or temporal arteritis is a systemic disease that nevertheless poses a threat to one’s ability to see and is therefore a medical emergency that must be treated right away to prevent irreparable damage to the eyes1. Unfortunately, the precise origin of the syndrome is still unknown, despite improvements in the understanding of the genetic and immunologic underpinnings of the disease1. Moreover, the common presentation for giant cell arteritis is visual symptoms, placing a crucial burden on the ophthalmologist to make an early diagnosis and initiate appropriate treatment1.

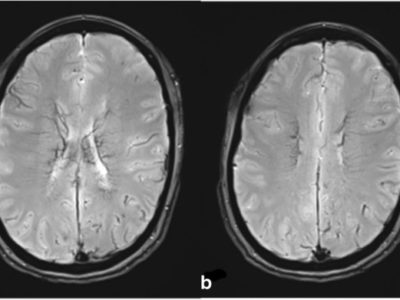

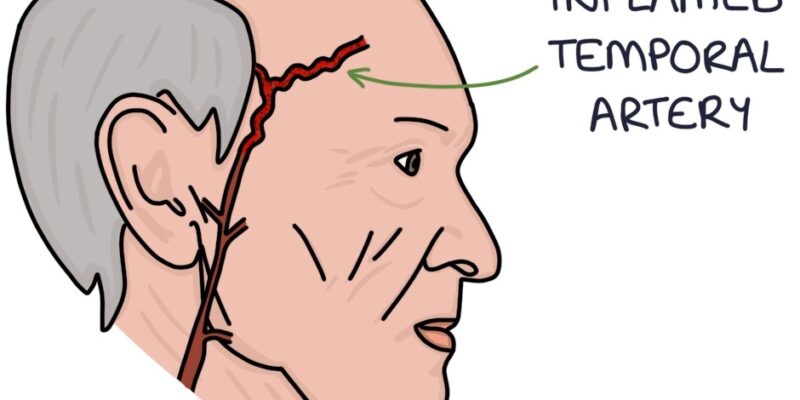

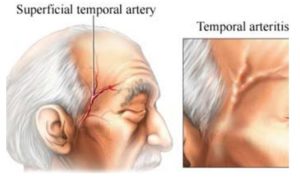

Figure (1): Thickening and scalp tenderness on presentation due to temporal artery vasculitis12.

Epidemiology and Etiology

GCA is the most prevalent kind of vasculitis in individuals over the age of 50. It rarely affects people under the age of 50, and the incidence increases considerably with age, peaking in the eighth decade of life3. Scandinavian countries and populations of largely Scandinavian heritage have recorded the greatest frequencies3. GCA was threefold more common in Scandinavia than the rest of Europe, and six times more common in Scandinavia than in East Asia2. Such phenomena could be explained due to genetic or environmental involvement.

Genetic susceptibility may explain the increased prevalence of GCA in Scandinavian nations2. Patients with GCA have haplotype diversity in particular MHC class II alleles, with HLA DRB1*04 being the most common2. TNF, adhesion molecules, and IL18 polymorphisms are sometimes linked to GCA2. Furthermore, because of more advanced healthcare tracking systems, rates in Scandinavia may be higher2. Also, smoking has been linked to an increased risk of GCA, particularly in women4. Several viral etiologies, including parvovirus B19, Mycoplasma, VZV, parainfluenza virus, Herpes virus, and Chlamydia, have been examined, but only circumstantial evidence without conclusive proof of an infectious etiology exists4.

Signs and Symptoms

Although non-specific, practically all patients with giant cell arteritis have one or more of the constitutional symptoms (weight loss, low-grade fever, exhaustion, anorexia, malaise)4. Furthermore, GCA is responsible for more than 15% of all fevers of unknown etiology in individuals 65 and older.

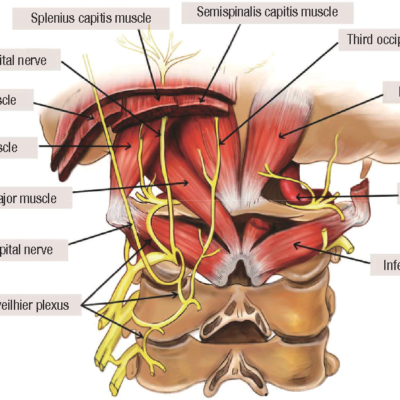

In an older patient, new-onset headaches or a change in baseline headaches should always raise worry about the possibility of GCA4. More than 75% of GCA patients experience headaches, which are typically temporal but can also be occipital, periorbital, or non-focal4. Headaches vary in strength and quality and can be severe and resistant to over-the-counter medications4. Scalp discomfort when combing or brushing hair is common and can be focal or diffuse in the temporal areas. Scalp necrosis is seen in rare and severe cases4.

Jaw claudication, or pain and discomfort while chewing or talking caused by decreased blood supply to the jaw muscles, is a relatively particular symptom of GCA that affects more than 30% of patients4.

Up to 50% of GCA patients have temporal artery enlargement, nodular swelling, discomfort, and pulse loss, which can be unilateral or bilateral4.

Visual manifestations occur in up to 15% of GCA patients and are most usually caused by anterior ischemic optic neuropathy caused by vasculitis involving the ophthalmic or posterior ciliary arteries. Patients may first experience transitory visual loss or amaurosis fugax4. Vision loss is usually rapid and painless4. It can be unilateral or bilateral at first, and there is a substantial chance of bilateral vision loss if unilateral vision loss is not treated immediately with high-dose corticosteroids4. Initially, fundoscopy indicates disc pallor and edema, followed by optic atrophy4. Diplopia can also be detected in GCA due to oculomotor nerve palsy caused by ischemia, and it frequently precedes visual loss4.

Polymyalgia rheumatica and GCA have similar etiology4. PMR is characterized by synovitis and peri arthritis involving the shoulder and hip girdles, resulting in discomfort, stiffness, and loss of range of motion of the bilateral shoulder and hip girdles4. PMR can occur before, alongside, or after GCA4. Furthermore, PMR affects 40–60% of GCA patients4.

Lastly, 30% of patients experience neurological symptoms and 10% have extra-cranial symptoms4. GCA can cause transient ischemia or strokes, particularly in the posterior circulation. Notably, GCA does not affect intracranial arteries4. Next, up to 10% of GCA patients have a dry or productive cough (with or without sputum), a painful throat, or hoarseness of voice4. Extracranial involvement occurs in 10-15% of GCA patients, including the thoracic or abdominal aorta and its branches, including the carotid, subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries4. Lower extremity arterial involvement is rare4.

Diagnosis

To avoid compromising the contralateral eye, early diagnosis and therapy are required5. In addition, various diagnostic imaging methods must be used to strengthen the sensitivity and closure of the diagnosis of temporal arteritis5.

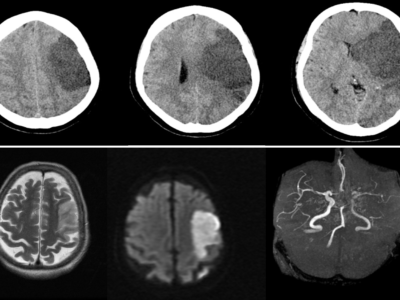

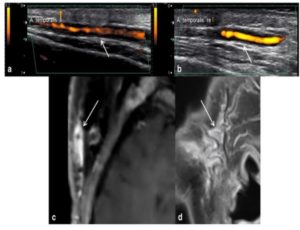

The latest EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis (LVV) advocate ultrasound of temporal arteries as the first imaging technique in patients with suspected cranial GCA6. The four major US findings in GCA patients are vessel wall thickness or halo sign, non-compressible arteries or compression sign, stenosis, and occlusions6. Such findings can be seen in the image below11, figure (2).

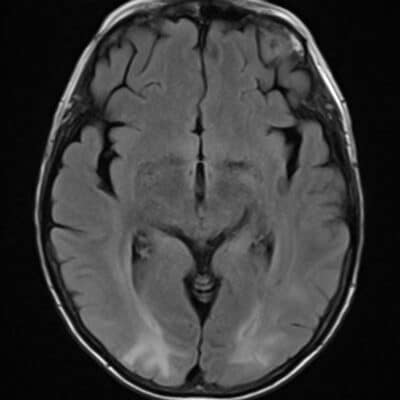

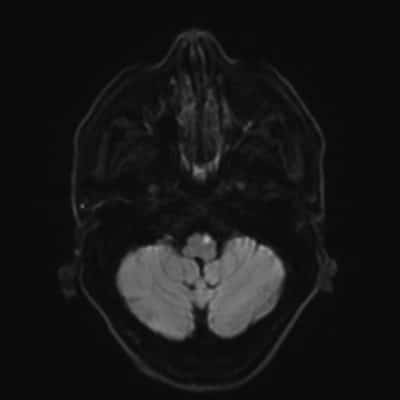

Figure (2): High-resolution MRI has been demonstrated to be useful for diagnosing and monitoring GCA over time6. On high-resolution post-contrast images, vasculitis appears as increased vessel wall thickness and edema with increased mural enhancement6. The most current EULAR guidelines advocated using high-resolution 3-T MRI of cranial arteries for GCA diagnosis if the US is unavailable or inconclusive6.

CTA is another method of diagnosing extracranial LVV-GCA6. In patients with LVV, there is mural thickening with double-ring enhancement after an intravenous infusion of iodine-based contrast6.

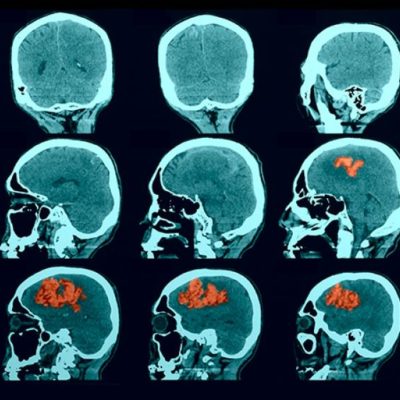

18F-FDG-PET combined with CT is a functional imaging technique that has demonstrated usefulness for LVV diagnosis due to its ability to detect glucose uptake from the high activity of inflammatory cells in the vessel walls6. PET/CT yields an exceptional overview of the extension of vascular inflammation. In addition, it is useful to rule out other entities such as malignancy or infection6.

The gold standard for diagnosing GCA is TA biopsy (TAB), which reveals a non-necrotizing granulomatous panarteritis with an inflammatory cellular infiltrate composed of mononuclear cells (T lymphocytes and macrophages), sometimes giant cells, fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina (IEL), destruction of the media, and hyperplasia of the intima, resulting in vascular lumen stenosis7. The presence of an inflammatory infiltration in the media and/or intima is required to confirm the diagnosis of GCA7. Pathognomonic but inconsistent elastophagy of the IEL and/or large cells. GCA does not cause intimal hyperplasia, which becomes more common with age, or IEL dissociation7. TAB sensitivity ranges from 60% to 80%7.

Management

Corticoids remain the treatment of choice in temporal arteritis; however, given the clinical variability of the disease and the unique characteristics of this patient group, which is typically older people and has systemic diseases, individualized treatment with coherent therapeutic guidelines is essential8. In refractory scenarios, intravenous mega-doses, antiplatelet therapy, methotrexate or TNF inhibitors, and surgical procedures may be considered8.

High-dose oral glucocorticoid therapy should be begun as soon as feasible in individuals without stroke or transient or permanent vision loss to avoid stroke or visual impairment that may arise during the acute phase of the disease9. Indeed, rapid treatment of suspected GCA has been linked to an 88% reduction in permanent sight loss9. Methylprednisolone pulse treatment has been proposed to prevent additional vision loss in patients with ischemic symptoms9.

Long-term usage of GCs is linked to osteoporosis, infection, or diabetes, which are serious concerns in older people, despite improvements in side effect prophylaxes9. To decrease patient exposure to GCs, recurrence rate, and less frequently, remission induction rate, immunosuppressant therapy has been studied9. Dapsone was discovered to be useful as an adjunct to GC or as a GCs-sparing drug in relapsing GCA9. However, because of the various side effects that patients reported, such as skin rashes or agranulocytosis, it is no longer regarded as a secure option9. It was discovered that hydroxychloroquine was linked to a high rate of skin toxic effects, along with an increased relapse rate during follow-up, which precluded further evaluation9. Despite having a high risk of adverse effects, cyclophosphamide has been shown in several retrospective researches to be a potential treatment for refractory disease9.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-a) has been found in inflamed arteries by immunohistology research9. Since 2010, there has been a growing interest in Tocilizumab (TCZ), a monoclonal antibody that targets the a-chain of the IL-6 receptor9. Following multiple case series, two randomized controlled trials demonstrated that TCZ could have a significant influence on relapse prevention or as a GCs-sparing drug. In individuals with newly diagnosed or relapsing GCA, TCZ has the most evidence as a GC add-on therapy9. In research that compared TCZ, either IV or subcutaneous, to abatacept subcutaneous, TCZ was found to produce vasculitis remission more frequently and to have a greater steroid-sparing effect than abatacept9.

Prognosis

The short- and long-term prognosis of patients with LV-GCA vary according to the pattern of vascular involvement. Because of the lower prevalence of visual complaints or permanent vision loss, morbidity linked to impaired vision is often lower in patients with LV-GCA than in those with cranial GCA10. Large-vessel stenosis can potentially cause ischemic consequences such as limb claudication; nevertheless, in most individuals, the formation of collateral circulation is adequate to sustain tissue viability10. Critical limb ischemia is extremely rare, and vascular bypass surgery is rarely required10. Revascularization should only be conducted during the dormant phase of the disease10.

Long-term prospective studies comparing individuals with isolated cranial GCA vs cranial GCA with evidence of large-vessel involvement vs isolated LV-GCA have yet to be conducted10. As a result, there is little and conflicting information about the true effects of large-vessel participation on long-term results10.