Title: Bulimia Nervosa

Author: Sara Awwad

Editor: Ihdaa Mahmoud Bani Khalaf , Sadeen Eid

Reviwer: Ethar Hazaimeh

keywords: Bulimia Nervosa, Bulimarexia, Bingeing

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are psychiatric conditions that seriously harm a person’s physical and mental health. 2 The manifestation of these concerns differs by gender; for example, problems with body image in men may emphasize muscularity, whereas, in women, these problems may emphasize weight loss more.3 Over 30 million people are affected by eating disorders, which are also significantly associated with morbidity and mortality. 4 The word “bulimia” which means “ox hunger” in Greek, was created to emphasize the characteristic of “gross overeating”. 5 Bulimia Nervosa (BN), which is also called Bulimarexia or Bingeing, belongs to EDs, it is a mental disease characterized by emotional disturbances that are addressed by consuming large amounts of food and then vomiting to avoid weight gain.6 Such behavioral patterns compromise neurobiological functions and have a negative influence on both physical and mental health. 5 Although it affects both sexes, Bulimia Nervosa often manifests in adolescence or early adulthood and is far more common in girls and young women. It affects individuals, regardless of sexual orientation, but non-heterosexual (Non-heterosexual is an umbrella term, describing homosexual, bisexual, asexual, and other people who do not identify as heterosexual) males have been demonstrated to have a higher prevalence.7

Epidemiology

There are some methodological issues with epidemiological studies on eating disorders. In the community, eating disorders are quite rare, and getting help is frequently avoided or postponed. The lifetime prevalence rates of Bulimia Nervosa are up to 3% of females and more than 1% of males suffer from this disorder during their lifetime. Over time, there has been a decrease in the overall incidence rate of bulimia nervosa. Moreover, it may carry five or more times increased mortality risk. 7

Correlates and comorbidities

Several correlates exist for patients with Bulimarexia. These correlations include things like childhood obesity, sexual abuse, low self-esteem, parental substance use and obesity, parental expectations, and previous dieting. Other examples, such as a history of psychiatric disorders and substance abuse, are more likely to be ascertained in an Eating Disorder encounter. Between 69.4% and 94.5% of Bulimarexia patients apparently meet the criteria for at least one additional DSM-IV disorder. Anxiety disorders range from 40.0% to 80.6%; mood disorders range from 49.9% to 70.7%, major depressive disorders comprising 31.0% to 50.1%; impulse-control disorders range from 9.54% to 63.8%.8

Pathophysiology

There is a great deal of confusion surrounding the definition of eating disorders, including whether they should be considered difficulties with eating or body image or neurotic, psychotic, or psychosomatic disorders. 10 Research on the fundamental causes of eating disorders is ongoing. Understanding these illnesses is likely more challenging by interactions between genetic and environmental factors at a critical stage of development. 2

Etiology

Bulimia Nervosa is a psychogenic disturbance in eating behavior characterized by episodes of uncontrollable eating binges that are frequently followed by self-induced vomiting, fasting, or the abuse of laxatives to prevent ensuing weight gain.11 Among the elements reported to influence the growth of bulimia are social influences which include the thin-ideal body image espoused for women as the shrinking ideal body image for women, the increasing number of dieting articles and advertisements in women’s magazines, the centrality of appearance in the female gender role, and the importance of appearance for women’s societal success. 9

Eating disorders seem highly heritable, with an estimate between 0.55 and 0.62 for BN. The hereditary risk for Eating Disorders (EDs) appears to vary by gender. Particularly, sex steroids might be crucial (as moderators or mediators) in the expression of ED behaviors. The genetic risk for developing an ED is 50% higher in men than it is in women before puberty. After puberty, the male risk remains steady, but the female risk rises to 50%. This sharp rise in risk for females (which is steady until puberty) suggests that genetic risk has been activated, most likely in connection with the start of puberty, and emphasizes the potential role of estrogen in risk activation. 10

In a sample of monozygotic twins with normal body mass index, those with higher estrogen levels had more ED symptoms. The serotonin system and brain-derived neurotropic factor genes, both of which are linked to ED symptoms, are controlled by estrogen. According to one study, men who have a female twin are more likely to get an ED than those who have a male twin. As a result, genetic data emphasize the significance of puberty in the emergence of EDs in females and implicate sex hormones, particularly estrogen, as key players in this process. 10

DSM-5 Diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa 11

-

- Frequent binge eating incidents. Two of the following characteristics describe an episode of binge eating: 13

- Eating, in a discrete duration of time (e.g. within any 2-h period), the quantity of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances 13

- Lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g., a feeling that one can’t stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). 13

- Repeatedly using unhealthy coping mechanisms to avoid gaining weight, such as self-induced vomiting, abusing laxatives, diuretics, or other drugs, fasting, or engaging in excessive exercise.

- In general, throughout the course of three months, binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur at least once per week.

- Body type and weight significantly influence how one feels about oneself. Food addiction not observed in YFAS

- The disruption does not just happen during anorexia nervosa episodes. 11

Complications

Skin

Russell sign It is pathognomonic for self-induced vomiting and results from repeatedly inserting the hand into the mouth to cause vomiting while being traumatized by the teeth. Since many of these patients may vomit on their own or with the help of objects, the Russell sign is rarely observed in them. 6

Teeth and mouth

Abnormalities of the teeth and mouth, specific c for purging via vomiting, including dental erosions and damage to the oral mucosa and pharynx. Dental erosions are irreversible and are the most common oral manifestation due to chronic regurgitation. It is also thought that trauma to the oral mucosa, particularly the pharynx and soft palate, arises from the patient putting something foreign in their mouth to induce vomiting or the caustic effect of the vomitus on the mucosal lining. 6

Head, ears, nose, and throat

The danger of subconjunctival hemorrhages increases with violated vomiting, and this can also result in recurrent epistaxis. Because the pharyngeal tissue comes into contact with stomach acid regularly in those who frequently vomit, pharyngitis is usually observed. The development of hoarseness, coughing, and dysphagia is also possible. 6

Parotid gland

More than 50% of patients who self-induce vomiting to purge may get parotid gland hypertrophy or sialadenosis.6

Cardiovascular

Electrolyte changes brought on by vomiting and diuretics or laxatives are among the cardiac problems that are specifically associated with purging. People who engage in various forms of purging are increasingly more likely to experience conduction problems, including severe arrhythmias and QT prolongation, as a result of the electrolyte imbalances that result, particularly hypokalemia and acid-base disorders. Ipecac, which includes the cardiotoxic alkaloid emetine, can cause numerous conduction disturbances and possibly irreparable cardiomyopathy when consumed in excess.6

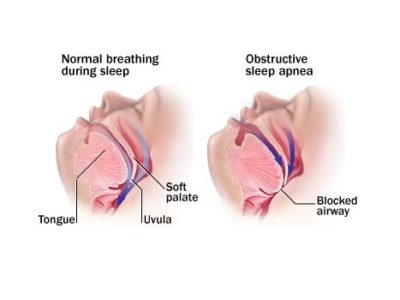

Pulmonary

vomiting increases intrathoracic and intra-alveolar pressures, which leads to pneumomediastinum. Pneumomediastinum may also come across nontraumatic alveolar rupture in the setting of malnutrition and therefore nonspecific in differentiating patients who purge from those who restrict.6

Gastrointestinal

- Esophageal complications excessive vomiting increases the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease and other esophageal problems, such as Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, by exposing the esophagus to gastric acid and damaging the lower esophageal sphincter. Uncommon complications are esophageal rupture, known as Boerhaave syndrome, and Mallory-Weiss tears. 7

- Colonic inertia. people engaging in excessive and chronic stimulant laxative abuse may be at risk for a “cathartic colon,” a condition whereby the colon becomes an inert tube incapable of moving stool forward. 7

- Melanosis Coli, black discoloration of the colon of no known clinical significance.6

Endocrine

Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, previously known as diabulimia but now known as eating-disorder Diabetes Mellitus type 1, may manipulate their blood glucose levels as a means of purging calories. The risk factors for these patients include severe hyperglycemia, ketoacidosis, and early microvascular sequelae such as retinopathy and neuropathy.6

Effect of covid 19 among patients with EDs

The lockdown and the stay-at-home regulations made this population more isolated and lonely mainly for people who live alone. A systematic review aimed to determine how the coronavirus lockdowns affected the severity of ED symptoms. The results were that concerns about one’s looks and body image were more prevalent in women and young individuals and they had a higher chance of their eating disorder symptoms getting worse during the COVID-19 lockdown.12

Management

The first steps in treating a patient with BN are medical stabilization and, if necessary, correction of any electrolyte imbalances (The most hazardous BN consequence is the emergence of an electrolyte imbalance, which can result in cardiac arrhythmia, seizures, and death) 5. Hospitalization may be necessary for medical instability (including severe bradycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and seizures), dehydration, hypokalemia, arrhythmia, excessive bingeing and purging, suicidality, or failure of outpatient treatment.4

Treatment

Adults treatment Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

The first-line treatment for adults with BN is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Dieting eventually results in binge eating, which then encourages the practice of inappropriate compensatory behaviors (such as self-induced vomiting, laxative and/or diuretic abuse, and excessive exercise), reaffirms body image problems, and motivates attempts to quit dieting. The cognitive-behavioral model of BN, therefore, postulates that concerns about one’s weight and form and eating disorder behaviors are mutually reinforcing and sustain a vicious cycle that maintains BN. CBT-BN uses an approach to introduce behavioral techniques and cognitive strategies to target symptoms delineated in the cognitive behavioral model of BN. The procedure is carried out in roughly 20 sessions over roughly 6 hours a month. CBT-BN first focuses on behavioral therapy because the doctor aids the patient in controlling their eating Behavior patterns and self-evaluation. 13

Treatment for children and adolescent

Family-based Treatment (FBT)

The goal of family-based treatment for BN (FBT-BN) in adolescents is to restore normal adolescent development while also normalizing adolescent eating patterns and empowering parents. The fundamental tenants of (FBT BN) include agnosticism with respect to the cause of BN. Parents are also believed to possess the knowledge and resources necessary to aid in their child’s recovery from BN. Three phases of the FBT-BN are presented over the course of 20 sessions or roughly six months. Parents are entrusted with interrupting their adolescent’s eating disorder behaviors in the first phase of FBTBN by giving them regular meals and snacks and keeping an eye on them afterward to prevent inappropriate compensatory actions. In the second phase, the adolescent gradually regains developmentally appropriate authority over meals and snacks when the eating disorder behaviors have been resolved. After achieving developmentally adequate autonomy in feeding themselves, the adolescent enters Phase 3, which focuses on addressing typical teenage development concerns and assisting the adolescent in creating an identity outside of BN. The teenager is weighed at the start of each session of FBT-BN.13

Pharmacotherapy

Psychotherapy is considered the treatment of choice for BN. In the event that psychotherapy is unavailable or unsuccessful, pharmacotherapy may be considered as a stand-alone treatment for BN. Research suggests that a combination of CBT and medication was superior to medication alone in promoting reductions in BN symptoms. Until now no psychotropic medications have been developed to treat BN specifically. Rather, medications developed for other conditions, antidepressants and antiepileptics are used .13

Prognosis

According to a 10-year follow-up study including 50 bulimia nervosa patients from a placebo-controlled trial of mianserin treatment, 52% of those who received the placebo had totally recovered, and just 9% still had all of their bulimia nervosa symptoms. In a bigger study, 222 participants from an antidepressant and organized, intense group treatment experiment were examined. It was discovered that after a mean follow-up of 11.5 years, 11% of the participants still fit the criteria for bulimia nervosa, while 70% were in full or partial remission. Shorter sickness duration, earlier age of onset, greater social class, and a family history of alcohol misuse have all been linked to a good prognosis. A history of substance abuse, premorbid and paternal obesity, and, in some studies, a personality problem have all been linked to poor prognosis. Early progress (a reduction in the purging of >70% by session) was the best indicator of outcome in an evaluation of the response to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). But a further systematic review of the outcome literature discovered no indication that early intervention is associated with a better prognosis. Only four pretreatment predictors of a poor outcome for the treatment of bulimia nervosa were consistently identified in a systematic review evaluating the cost-effectiveness of treatments and prognostic indicators: characteristics of borderline personality disorder, concurrent substance abuse, a lack of motivation for change, and a history of obesity.14

Conclusion

According to Treasure et al., “Eating disorders are incapacitating, fatal, and expensive mental diseases that significantly worsen physical health and disrupt psychosocial functioning.” This makes finding effective treatments even more crucial. A different perspective on the burden of illness is to consider the costs to the person and society. Treatment expenses, a direct financial impact, and lost income for both patients and caregivers are all part of the disease costs associated with ED 15. BN’s main symptoms are attempts to shed weight and a fear of being obese. Although patients with BN typically weigh within a normal range, some fall in the higher or lower normal limits.16 Effective psychological therapies exist, particularly cognitive behavior therapy (CBT).15