Neurosurgery Insights

Dr. Omar Jbarah

Conducted by:

Dr. Omar Jbarah

Neurosurgery Specialist, Founder and General Director of Neuropedia, Fellow in Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery (Japan)

Session 1: Introduction to Neurosurgery & Its Importance

- Overview of Neurosurgery:

- Definition and scope (brain, spine, peripheral nerve surgeries).

- Why neurosurgery is critical for patient care.

- Role of a Neurosurgeon:

- Lifesaving interventions: brain trauma, tumors, vascular conditions.

- Examples of high-impact neurosurgical cases.

- Neurosurgical Subspecialties:

- Cranial surgery, spine surgery, pediatric neurosurgery, functional neurosurgery , etc.

- Interactive Q&A: Why attendees are interested in neurosurgery.

Session 2: Hot Topics in Neurosurgery

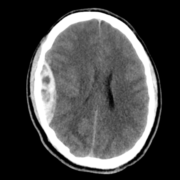

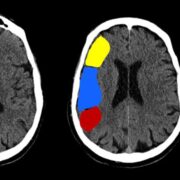

- Brain Surgery:

- Vascular Neurosurgery ( Aneurysm , AVM , etc. )

- Brain Tumor Surgery (e.g., Gliomas, Meningiomas).

- Minimally Invasive Techniques (Endoscopic Surgery).

- Functional Neurosurgery: Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson’s, epilepsy surgery..

- Spine Surgery:

- Degenerative Spine Conditions (herniated discs, stenosis).

- Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery.

- Real-life Cases: Patient journey from diagnosis to recovery.

- Discussion: How technology is shaping the future of neurosurgery.

Session 3: Pathway to Becoming a Neurosurgeon

- The Training Journey:

- Medical School Requirements.

- Neurosurgery Residency (years, structure, challenges).

- Subspecialty Fellowships (cranial, spine, pediatric, etc.).

- Essential Skills: Technical proficiency, problem-solving, teamwork.

- Daily Life of a Neurosurgeon:

- Case examples: Trauma care, emergency surgeries, elective surgeries.

- Stress and rewards: The high stakes and emotional fulfillment of the job.

- Why We Need Neurosurgeons:

- Addressing the global shortage.

- Neurosurgeons as pioneers of innovative treatments.

- Q&A: Navigating the path and career motivations.

Session 4: Life After Becoming a Neurosurgeon

- Career Paths:

- Clinical Practice vs. Research vs. Academia.

- Global Health and Neurosurgery: Humanitarian missions, making a difference in underserved areas.

- Challenges and Rewards:

- Balancing personal life and career.

- The emotional resilience needed for high-pressure situations.

- Opportunities for continuous learning and advancement in neurosurgery.

- Future of Neurosurgery:

- What’s next? AI, VR, and cutting-edge advancements.

- Telemedicine and global collaboration.

- Panel Discussion with Neurosurgeons:

- Insights from established neurosurgeons on their journey and advice for students.

Course Structure:

- Start Date : 4-10-2024 (Friday)

- Duration: 1.5 – 2 hours weekly sessions (Every Friday – 6:00 PM )

- Format: Online Sessions – 30-minute presentation followed by 60 minutes of interactive discussion, Q&A, and case studies.

- Goal: To provide students with a clear understanding of neurosurgery as a career, its innovations, and the vital role it plays in healthcare.

- Fees: 50 JD – Cliq or Zain Cash Transfer to 0795069358