Author: Mario Chahwan , Elias Abboud

Editor: Christie Dib

Reviewer: Jaber Jaradat

Keywords: Kleptomania; Stealing; Shoplifting; Mental health disorder; Impulse control disorder

Abstract

Kleptomania, characterized by recurrent urges to steal non-valuable items, has been recognized as a psychiatric disorder since its official classification in 1980. Despite its rarity in the general population, its prevalence in individuals arrested for shoplifting is notable. The etiology and pathogenesis of kleptomania involve complex interactions between biological and psychological factors. Dysregulation of neurotransmitter systems, particularly serotonin, dopamine, and the opioid system, contributes to the development of impulsive stealing behaviors. Psychological theories also implicate early emotional deprivation and psychosexual issues in the pathogenesis of this disorder. The diagnosis of kleptomania requires careful evaluation considering its overlap with other psychiatric conditions. Physical examinations and psychological assessments, along with standardized diagnostic instruments, aid in accurate diagnosis and validation of the disorder. Treatment options, including pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, aim to address both impulsive behaviors and the underlying psychological factors. Despite the challenges in treatment, early intervention and a multidisciplinary approach hold promise in managing kleptomania.

Figure 1: key words describing kleptomania [15]

Introduction

Kleptomania is a recurrent urge to steal unnecessary or unvaluable objects. It was derived from the French word “kleptomanie” meaning “stealing madness”, as described by two French psychiatrists, Marc and Esquirol, in the nineteenth-century [2]. One of the first documented cases of kleptomania was recorded in 1799 in the British legal system. Cases of kleptomania in America started to be referenced in the literature as far back as 1878 [1]. It was officially classified as a psychiatric disorder in 1980 [2].

Prevalence

Kleptomania is a rare disorder, with approximately 0.3 to 0.6% prevalence in the general population and 4 to 24% in people arrested for shoplifting. It is three times more common among females than males, and one explanation behind this difference is that men are more likely to be sent to prison after being arrested, instead of being referred to treatment [1, 3].

Etiology and Pathogenesis

- Biological theories: Multiple neurotransmitters are involved.

- Serotonin:

Blunted serotonergic responses in some brain areas have been attributed to poor decision-making, which can be seen in patients with kleptomania [2]. Cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (CSF 5-HIAA) is a serotonin metabolite that correlates with impulsivity, when it is low in the forebrain, individuals are prone to high levels of impulsivity, risk-taking, excitement-seeking, and vice versa [6]. However, the inhibitory mechanisms of impulsivity proved to be reduced, involving the serotonin and prefrontal cortex. However, other pathways like the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and hippocampus, are also probably involved in the mechanism [2].

- Dopamine:

Dopamine, a reward hormone released in the nucleus accumbens, serves as a “go” signal and produces a pleasure sentiment. Furthermore, its release is maximal when the probability of success is very low. Each rewarding experience seems to result in neuroplastic changes in the nucleus accumbens, affecting future behavior which is determined by prior rewarding experiences. This is the reason why some people with kleptomania may, over time, shoplift “out of habit” even without a pronounced urge or craving [2].

- Opioid System:

The μ-opioid system is believed to regulate urges via the processing of incoming reward inputs by the ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbitofrontal cortex (VTA-NA-OFC) circuit.

Additionally, opioids regulate pleasure and pain [2], partly via the activation of μ opioid receptors causing inhibition of GABA release with consequently increased dopamine release, knowing that GABA is the brain principal inhibitory neurotransmitter [6].

In summary, an imbalance between a pathologically increased urge and a pathologically decreased inhibition results in kleptomaniac behavior. Those conducts may therefore be the result of the increased activity of the dopamine circuitry, indirectly enhanced by the opioid system, and decreased activity in the cortical inhibitor processes, which are mainly influenced by serotonin [2].

- Psychological theories:

There are psychological, developmental, and biological factors most likely involved in the pathogenesis of this disorder. Some data put forward that kleptomania can be linked to depression and childhood development. According to some theories, the stimulation by shoplifting may relieve depression by distracting individuals from life stressors and uncomfortable cognitions. To those people, stealing objects becomes an attractive mean of escape since it does not lead to intoxication and does not impair the ability to work. Therefore, depressed people may view the possibility of being apprehended as a relatively minor setback [2].

Early emotional deprivation_ like having abusive or neglectful parents_ besides psychosexual issues _such as sexual repression and depression_[3] can also be implicated in the pathogenesis of this disorder. When someone shoplifts then leaves the store successfully without being apprehended, this may raise his or her esteem [7].

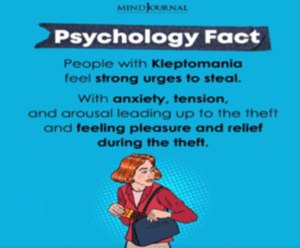

Symptoms

Figure 2: Main symptoms of kleptomania [15]

Subjects with kleptomania usually present these clinical manifestations [7, 8, 10, 13]:

- Stealing suddenly without prior planning and help from others.

- Feeling satisfaction, delight, and enjoyment during the act.

- Feeling guilt and shame after the theft.

- Incapacity of preventing the robbery from happening.

- Stealing frequently and repeatedly despite the self-awareness of the legal outcomes given that the tendency of stealing is permanent

- Returning the stolen items, throwing them away, or even giving them to charity, as most individuals with kleptomania do not purloin the objects for their gain.

Most of these complications are usually the motive that drives the patients to visit their healthcare provider(s) and form the fundamentals that the medical expert will rely on to diagnose the case.

Diagnosis

kleptomania diagnosis is not always easy due to its close link with other psychiatric comorbidities which implies careful and accurate evaluation [10].

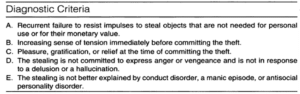

The main diagnostic feature is the uncontrollable impulse of stealing items that are non-valuable to the concerned person [10]. Table 1 presents the DSM guidelines for Kleptomania.

Table 1: Diagnostic criteria of kleptomania according to DSM-V [1]

Table 1: Diagnostic criteria of kleptomania according to DSM-V [1]

Note that: clinical trials have shown that kleptomania patients may suffer from a difficult childhood or inferior quality of life as they often report a lack of self-esteem and have high rates of attempted suicide [14].Consequently, having an accompanying anxiety disorder, personality disorder, substance use disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, affective disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [10].

In addition, kleptomania patients have an elevated risk of legal issues, and troubled relationships; several studies of clinical samples of patients with kleptomania have shown that 64-87% of these patients have been arrested [13].

Physical exams as well as psychological evaluations are often required. Here are some tests recommended to rule out other conditions and validate the diagnosis [13]:

Firstly, a valid diagnostic instrument that incorporates all DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania would be the Structured Clinical Interview for Kleptomania (SCI-K).

Secondly, the Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI), consists of a score from 1 to 7, used to assess the severity of the illness.

Thirdly, the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale (K-SAS) is an 11-item self-report scale that also assesses the severity of clinical symptoms of the disease.

Similarly, the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) is a 3-question, self-report measure that examines the effect of kleptomania in three domains: occupational life, social life, and family life.

Differential diagnosis

- Bipolar disorder: As stated in the diagnostic criteria in DSM-5, stealing should not be explained by other mental disorders and manic episodes, which is the case in Bipolar Type 1 Disorder. Additionally, cases of stealing during these mood episodes continue for a few weeks whereas kleptomania is more persistent and long-lasting [7].

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): While patients with kleptomania express happiness and excitement during the theft, this emotional pattern is absent in individuals with ADHD [11].

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: The theft is committed in response to an unwanted anxiety-provoking obsession. Nevertheless, stealing in kleptomania is not induced by an intrusive situation; it happens spontaneously without any planning [11].

- Conduct-Dissocial Disorder: individuals with this type of disorder steal for their gain or seek revenge, as these complications take part in antisocial behavior that cannot be diagnosed as kleptomania according to the DSM-5.

Treatment

Patients with kleptomania rarely seek medical attention voluntarily, but usually after a legal mandate [3].

- Pharmacotherapy

Currently, no medication has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating kleptomania [2]; however, some drugs can be used for these patients, as they have been shown to be effective in some studies.

SSRIs/SBRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [3] and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are antidepressants that influence the serotonergic system. Moreover, they showed good results in reducing kleptomaniac symptoms by reducing shoplifting thoughts and improving social functioning [2].

Antidepressants may be associated with opioid antagonists in cases where a kleptomaniac patient presents with impaired inhibition of behavior and urge regulation [2].

Naltrexone

One open-label trial showed that naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, with a mean dose of 145 mg/day led to a notable decline in the intensity of urges to steal, stealing thoughts, and stealing behaviors. A lower dose of 50 mg/day, seems effective in younger people with this condition [2].

Topiramate

Topiramate, an anticonvulsant drug, proved to be effective in impulse control disorders (ICD) such as kleptomania [3]; however, their side effects limit their wide use and is the underlying cause of poor compliance [5].

It is recommended to start treating these patients with SSRI or SNRI and adjust for the right dose and duration. However, in insufficient response, naltrexone or topiramate are the next choice [3].

- Psychotherapy

Several methods have been used to treat kleptomania:

Covert sensitization consists of imagining the negative outcomes of being caught stealing [5] or using images of nausea or vomiting whenever urges come [2]. This type of covert sensitization showed high rates of success [5].

Aversion therapy involves the use of approaches such as aversive breath-holding, which induces unpleasant sensations whenever the urge to steal arises [7]. Moreover, the use of relaxation techniques reduces the sensitivity and tension experienced when urges appear [3]. Additionally, using a diary of the urges to steal may increase the chances of success of the therapy [3].

While psychoanalysis results showed limited success in the modification of kleptomaniac behavior, cognitive behavioral therapy has shown promising results in reducing and controlling actions related to kleptomania, especially with the aid of medications [2, 7].

Treatment of this impulsive-control disorder represents a large area of future research, especially when combining pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy. However, empirically validated medications and interventions for treating kleptomania are required [2].

Risk factors and Comorbidities

A large association has been found between majorly depressed individuals and kleptomania. Furthermore, kleptomania has been associated to a lesser extent with anxiety or eating disorders [3]. In addition, addiction, depression, personality disorders, mood disorders, and substance abuse are all psychiatric conditions associated with kleptomania [3, 4].

Furthermore, traumatic brain injury and various brain lesions [4] can be neuropsychiatric sequelae of impulse control disorders. It is also possible that brain disorders such as frontotemporal dementia and epilepsy result in kleptomania [3].

Likewise, social isolation and high levels of perceived stress are linked to increased intensity and/or frequency of kleptomaniac behaviors [5]. Comparatively, first-degree relatives of individuals with kleptomania may have higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder than the general population [1]. At the same time, kleptomania has been reported as a paradoxical side effect of SSRIs in three patients who were taking SSRIs as a treatment for depression [3, 4].

Conclusion

Kleptomania presents a challenging psychiatric disorder with lifelong implications. However, with early and appropriate intervention by trained clinicians, individuals can gain control over their impulses and reduce the impact of the disorder on their lives. Future research should focus on empirically validated pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy approaches to improve outcomes in individuals with kleptomania. Further investigation of the risk factors and comorbidities associated with the disorder is essential for a solid understanding and effective management of kleptomania.

References...