Article topic: Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia

Author: Sarah Mahfouz, Ziad Azar

Editors: Lubna AL-Rawabdeh

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

keywords: Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia, medial longitudinal fasciculus, lateral gaze, multiple sclerosis, brainstem infarction.

Overview

Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO) is a visual disorder most prevalent in the elderly population, often associated with a history of multiple sclerosis (MS) or brainstem infarction.

INO results from damage to the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MFL), a bundle of nerves located in the brainstem, specifically in the paramedian area between the midbrain and pons. This disorder is characterized by a lateral horizontal visual impairment, marked by deficient adduction in one eye, the one adjacent to the lesion, and abducting nystagmus in the other [1]. First described in 1903, INO has since been better defined as a neurological condition and visual phenomenon [1].

In this article, we aim to introduce internuclear ophthalmoplegia, briefly describing its clinical features and etiological process. We will also unfold its relationship with multiple other disorders and syndromes, highlighting its diagnostic and clinical value.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

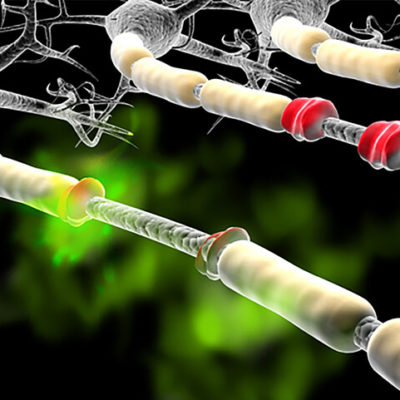

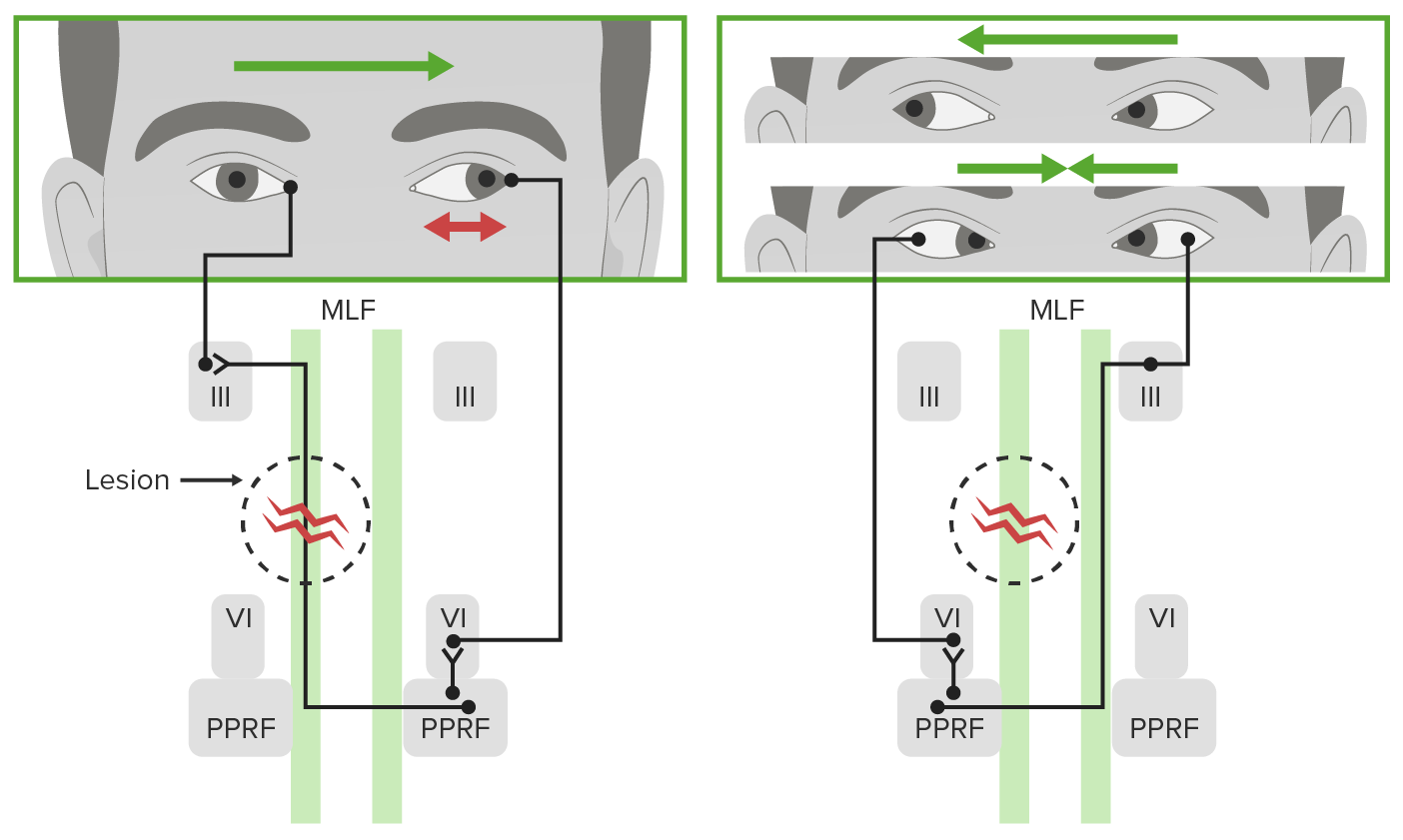

The medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) is a highly specialized and heavily myelinated fiber tract that establishes a crucial connection between the abducens nerve and the paramedian pontine reticular formation (PPRF), ultimately linking to the oculomotor nerve nuclei on the contralateral side [3]. This intricate neural pathway serves as the ultimate common denominator for various forms of ocular motility, Figure (1).

![Figure (1) : Internuclear ophthalmoplegia. Sharma R, Fahrenhorst-Jones T, Yap J, et al. Figure 1 displays the Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia diagram [2].](https://prod-images-static.radiopaedia.org/images/59467649/8c4ed1dd9f698125daab7c8d44c5a6a8fe99f2fc13b98e14213609bc2ae9eedc_jumbo.jpeg)

Figure (1): Internuclear ophthalmoplegia. Sharma R, Fahrenhorst-Jones T, Yap J, et al. Figure 1 displays the Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia diagram [2].A lesion affecting the MLF gives rise to a distinct form of ophthalmoplegia and can result in the impairment of horizontal conjugate eye movements, primarily due to the disruption of communication between the oculomotor nerve nuclei (III) and abducens nerve nuclei (VI) [1].

It is imperative to recognize that the MLF is susceptible to damage from a variety of sources: (demyelinating, neoplastic, inflammatory, ischemic …)

- Demyelinating

In younger patients, Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO) typically forms a component of multiple sclerosis (MS) presentations. It may even manifest as the initial symptom, as demyelination can impact various segments of the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (MLF), with bilateral INO being the most common outcome.

Additionally, INO may be a feature in other demyelinating syndromes such as Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein-IgG-Associated Disorder and Neuromyelitis Optica. In such instances, ophthalmoplegia can occur unilaterally or bilaterally.

- Ischemic

In the elderly population, lesions affecting the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (MLF) predominantly arise as a result of cerebrovascular accidents.

These incidents typically involve the small perforating paramedian arteries originating from the basilar arteries, responsible for providing blood supply to the region housing the sixth nerve nucleus. Simultaneously, the small perforating branches of the P2 segment of the posterior cerebral artery are responsible for irrigating the midbrain where the third nerve nucleus is situated.

Therefore, occurrences such as small embolic events, hypertensive strokes, vascular dissection, and vasculitis impacting these arteries can give rise to lesions within the MLF and subsequently lead to the manifestation of Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO) [3].

- Infections

Infections represent a less frequently encountered etiological factor contributing to Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO), and they can be categorized as follows:

- Bacterial infections, including conditions such as Syphilis and Lyme disease.

- Viral infections, encompassing diseases such as HIV and herpes zoster.

- Fungal infections, exemplified by cryptococcosis.

- Parasitical infections, with cysticercosis being an illustrative example.

- Other conditions

Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO) can be attributed to a spectrum of diverse underlying conditions, including but not limited to:

- Inflammatory disorders, such as Sarcoidosis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Behcet’s Disease, and Sjogren’s Syndrome.

- Tumorous growths comprise conditions like medulloblastoma, glioma, lymphoma, and metastatic tumors.

- Nutritional disorders, exemplified by Pernicious Anemia and Wernicke Encephalopathy.

- Toxic effects induced by drugs, with substances like lithium, narcotics, phenothiazines, and tricyclic antidepressants implicated.

- Traumatic head injuries.

- Congenital malformations, including the Arnold-Chiari malformation.

- Metabolic conditions, such as Fabry Disease and hepatic encephalopathy.

- Degenerative conditions.

- Iatrogenic causes.

- Subdural hematoma.

- Hydrocephalus.

Saccadic eye movements represent a pivotal ocular function in which the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (MLF) plays a substantial role. This intricate process involves the transmission of signals originating from the Frontal Eye Field (FEF) to the contralateral Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation (PPRF) and the rostral interstitial nucleus of the MLF, specifically for horizontal and vertical saccades, as elucidated in reference [4].

Subsequently, the PPRF serves to stimulate the ipsilateral abducens nucleus, which, in turn, conveys signals to the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle. Simultaneously, signals are transmitted through the MLF to reach the contralateral medial rectus subnucleus of the third cranial nerve nucleus. This coordinated effort results in the establishment of a horizontal gaze towards the eye opposite the initiating FEF.

As a fundamental diagnostic indicator in cases of Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO), the clinical presentation often includes deceleration or impairment of adduction in the affected eye on the same side as the lesion. In the contralateral eye, a dissociated nystagmus may manifest, believed to represent a compensatory mechanism aimed at mitigating the weakness observed in the adducting eye. This phenomenon aligns with Herring’s law of equal innervation, which posits that an increase in innervation to a muscle is accompanied by a corresponding increase in innervation to its yoke muscle. In the context of INO, these muscles are the medial rectus muscle and the contralateral lateral rectus muscle, as expounded in reference [1].

Figure (2): displays Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia [5].

The principal clinical hallmark characterizing a patient afflicted with internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) is the manifestation of either partial or complete ipsilesional impairment of adduction in conjunction with horizontal dissociated saccades and nystagmus directed contralaterally while attempting to fixate on an object situated in the direction opposite to the site of the lesion [1]. To illustrate, in the event of a lesion within the left medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) and an attempt to direct gaze to the right, one would observe dissociated nystagmus, characterized by an involuntary rhythmic eye movement [6], and/or saccades, which denote rapid eye movements following a sudden shift in the point of fixation [7], in the right eye. Simultaneously, there would be an impaired adduction in the left eye, instead of the expected normal leftward adduction and rightward abduction.

Concomitant symptoms attributed to MLF lesions may encompass a spectrum of manifestations, ranging from mild symptoms like headaches to more intricate complications indicative of brainstem dysfunction, including conditions such as aspiration pneumonia and respiratory failure [1]. Of particular note are:

- Dizziness, ranks among the most frequently reported symptoms associated with MLF impairment, especially when elicited during lateral gaze examination [8].

- Blurred vision [1].

- Difficulty in tracking rapidly moving objects [3].

- Horizontal diplopia, or double vision characterized by the lateral separation of two images, as a consequence of impaired ipsilesional adduction [3,9].

- Vertical diplopia, marked by one image appearing higher than the other, typically stemming from skew deviation. Skew deviation arises from asymmetric disruption of supranuclear input from the inner ear, leading to a misalignment of the eyes and prompting the ipsilateral eye to deviate upward (hypertropia) [1,3,9].

- Furthermore, disruptions in the coordinated horizontal eye movements may result in the loss of binocular vision [3].

- This, in turn, engenders visual confusion, wherein two distinct images are perceived as superimposed upon the same spatial plane [3,10]. Additionally, depth perception, as represented by stereopsis, may also be compromised [3].

- Oscillopsia, characterized by unstable vision due to the misperception of a moving environment [3,11], may ensue, alongside symptoms such as reading fatigue, among others [3].

It is important to keep in mind that these symptoms vary in intensity and likelihood depending on several factors, but mostly depending on the specific etiology of the presented INO.

- It is also important to note that visual difficulties looking sideways hampers the ability to drive or even walk properly, which increases the risks of car crashes and falls [3].

Figure (3): displays Binocular INO [3].

Table (1) displays the Type of pathology, location, presence of additional lesions, and neurological clinical signs and symptoms recorded for patients with a lesion in the medial longitudinal fasciculus on brain MRI. CVA: cerebrovascular accident, INO: internuclear ophthalmoplegia [12], Fiester P, Rao D, Soule E, Andreou S, Haymes D.

Workup and Diagnosis

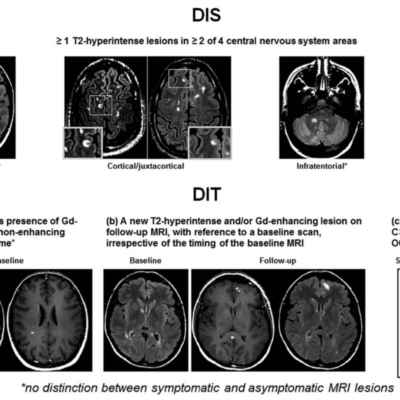

The diagnostic process for Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO) involves a thorough medical history and a meticulous physical examination, focusing on the evaluation of eye motion [8]. Clinical tests, such as assessing saccadic velocity and utilizing optokinetic drums or tapes, are essential for detecting subtle disconjugate saccades in the eye [3]. Upon diagnosis, additional tests, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are invaluable tools for further investigation [3]. In general, MRI is considered superior to CT for evaluating INO, with up to 75% of patients demonstrating visible damage to the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (MLF) on MRI scans [9]. Proton density imaging is particularly effective in detecting demyelinating lesions [1]. Less common causes may necessitate supplementary blood and cerebrospinal fluid studies.

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing INO from other neurological conditions is crucial. The following differential diagnoses should be considered:

- Lateral Gaze Palsy: This condition involves the inability to perform horizontal, conjugate eye movements in one or both directions and can result from lesions affecting the abducens nerve, Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation (PPRF), or the frontal or parietal eye fields [13].

- One-and-a-Half Syndrome: Characterized by a combination of a conjugate horizontal gaze palsy in one direction and INO in the opposite direction, this syndrome results from lesions involving the MLF, PPRF, and/or the abducens nerve [5].

- Pseudo INO: Symptoms resembling INO may occur due to peripheral conduction defects, such as Miller Fisher Syndrome and Myasthenia Gravis, rather than MLF lesions [14].

- Third Nerve Palsy: This condition, in addition to INO symptoms, presents with pupillary dilation, ptosis, loss of accommodation, absence of abduction nystagmus in the fellow eye, impaired convergence, and limitation of elevation [3].

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: This brain disorder causes issues with walking, balance, and eye movements similar to bilateral INO [3,15].

Treatment and Management

INO treatment strategies primarily depend on addressing its underlying cause. Treatment options vary accordingly. Symptomatic relief for diplopia can be achieved through botulinum toxin injections and the use of Fresnel Prisms [1]. Surgical intervention may be considered for strabismus correction, especially in cases of wall-eyed bilateral INO [1].

Incidences and Risk Factors

INO is associated with multiple sclerosis (MS), with studies indicating its occurrence in 15 to 52% of individuals with MS [16]. The prevalence of INO rises significantly with age, peaking around 52 years, but is rare in pediatrics [1]. Incidence is roughly equal for both genders.

Etiologically, one-third of INO cases result from infarctions, most often presenting unilaterally [1,17]. Another third is associated with multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating disorders, typically affecting younger individuals with a bilateral presentation [1]. The remaining third is attributed to head trauma, infections, brainstem injuries, hemorrhages, vasculitis (e.g., Sjogren Syndrome and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus), and certain tumors (especially pontine gliomas and medulloblastomas) [1]. Additional risk factors, such as vitamin D deficiency and a family history of individuals with MS, are linked to the underlying causes of INO [18].

Prognosis

The prognosis for most INO patients is generally favorable, with outcomes contingent on the underlying cause and treatment. Rapid recovery is observed when there are no other neurological signs, such as facial palsy, ataxia, hemiparesis, vertigo, pyramidal tract dysfunction, sensory symptoms, dysarthria, and no visible lesions causing INO [3]. Cerebrovascular disorders, brainstem demyelination, and trauma tend to result in a less favorable prognosis [1].

Recent Updates

Recent research has explored innovative treatments for INO. A study demonstrated that a single dose of 20 mg of fampridine significantly improved saccadic eye movement in 23 multiple sclerosis patients with INO, with sustained results for approximately 5 hours [19]. Additionally, stem cell remyelination, facilitated by the accessibility of the medial longitudinal fasciculus around the ventricles, holds promise for neuroprotection and restoration [1].

In terms of diagnosis, emerging techniques like proton density imaging and infrared oculography have shown promise in detecting INO in demyelinated patients, highlighting the potential for enhancing diagnostic precision in the field of neuroimaging [1,16].

References