Title: Delirium

Author: Sulieman Mazahreh

Editor: Fadlullah M. F. AL-Saleem

Keywords: Delirium, Acute confusion disorders, Psychiatry

Abstract

Delirium is a common and expensive acute confused condition that is accompanied by considerable functional impairment and discomfort. It is a symptom of acute encephalopathy and is variously referred to as acute brain failure, acute brain dysfunction, or changed mental state. All patients are at risk for delirium, however, those who are more vulnerable (such as advanced age, exposure to other stresses such as infection, and specific drugs) are at a higher risk. The pathophysiologic etiology of delirium is unknown. It is critical to identify patients at risk for and those who have delirium, as well as to identify and treat variables that contribute to it as soon as possible. Because there is no one action or drug to treat delirium, it is difficult to control. As a result, risk reduction and quick treatment are dependent on a thorough plan to address the relevant variables. When multimodal methods are employed, delirium can be avoided or reduced, improving patient outcomes.

History of Delirium

Delirium is one of the earliest described kinds of psychoses, however many medical professionals still see it as an unknown and unrecognized condition. (1) Hippocrates (5th century BC), the father of traditional medicine, initially identified phrenitis and paraphrenitis, which are today recognized as a somatic kind of delirium and referred to as variably expressed acute behavioral disorders that occur during physiological inflammation. (2)

Introduction

Delirium is a frequent and costly acute confusing disorder that causes significant functional impairment and suffering. It is a sign of acute encephalopathy and is also known as acute brain failure, acute brain dysfunction, or altered mental state.

It is difficult to regulate delirium since there is no one activity or treatment to cure it.

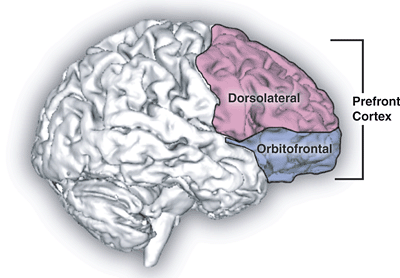

Etiology and pathogenesis

Despite its great frequency and morbidity, little is known about delirium. Advanced age, prior cognitive impairment drugs particularly those with significant anticholinergic potential, sleep deprivation, hypoxia and anoxia, metabolic abnormalities, and a history of alcohol or drug misuse are all known risk factors for delirium.(3) Several ideas have been offered throughout the years in an attempt to explain the mechanisms that contribute to the development of delirium.(4) Each suggested theory has concentrated on a certain mechanism or pathologic process, as well as observational and experience evidence or empirical data. However, no one unitary pathophysiologic mechanism has been found yet. (5)

Figure 1: Theories on the onset of delirium. Diagrams illustrating the interrelationships of current views on the pathophysiology of delirium and how they may be related to one another.

Maldonado JR. Neuropathogenesis of delirium. 2013;21(12):1190-1222. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.09.005

Clinical presentation

Delirium is characterized by a wide spectrum of cognitive and noncognitive neuropsychiatric symptoms in the areas of motor activity, sleep-wake cycle, emotional expression, perception, and thinking. This wide phenomenological spectrum reflects the pervasive disturbance of brain function and can resemble a variety of different neuropsychiatric illnesses. Regardless of its etiology, delirium has a uniform manifestation that shows the failure of a single common neuronal circuit.(6) Understanding specific symptom frequencies and patterns can give crucial information about the neurological foundations of this entity.(7)

Table 1

Frequency of phenomenological manifestations in delirium

Gupta N, et. al Res. 2008;65(3):215-222. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.020

Core diagnostic features

Attentional deficits (97–100%)

Thought process abnormalities (54–79%)

Other core symptoms

Disorientation (76–96%)

Memory deficits (88–96%)

Sleep-wake cycle disturbances (92–97%)

Motoric alterations (24–94%)

Language disturbances (57–67%)

Non-core symptoms

Perceptual disturbances (50–63%)

Delusions (21–31%)

Affective changes (43–86%)

Clinical subtypes

Motor behavior disturbances are almost always present and obvious in delirium. There are over 30 studies that demonstrate that motorically defined clinical subgroups of delirium differ in terms of the presence of nonmotor symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, detection rates, treatment experience, episode duration, and prognosis. However, data have been contradictory with improved prognosis in hypoactive individuals, hyperactive presentations, or patients with normal motor function.(8)

Lipowski distinguished between ‘hyperactive’ and ‘hypoactive’ psychomotor presentations, subsequently adding a third ‘mixed’ category in which parts of both occur within short time frames.(9) Liptzin and Levkoff developed criteria based on activity and related psychomotor activities.(10) O’Keeffe used questions from the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale to define delirium subgroups based on activity within the first 48 hours. Other ways include using symptom items from the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS), the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) and its most recent version (DRS-R-98), as well as visual analog scales and ‘clinical impression’.(11)

Workup and Diagnosis

The following are the characteristic elements of delirium as outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV): (12)

- Disturbance of consciousness (i.e., reduced clarity of awareness of the environment) with diminished ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention.

- A change in cognition (e.g., memory deficit, disorientation, language disturbance) or the development of a perceptual disturbance that is not better explained by a pre-existing, established, or evolving dementia.

- Disturbance occurs over a short length of time (typically hours to days) and tends to fluctuate throughout the day.

- Depending on the cause.

In the examination of delirium, clinicians encounter two diagnostic problems. The first step is to recognize that the illness exists, and the second is to evaluate the patient for any medical issues that may have provoked the event.

Despite developments in medical technology, the history and physical examination remain the cornerstones in the diagnosis of delirium. Further testing may be necessary after a comprehensive review; however, overreliance on laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging might reduce physician-patient contact, making the nuances of delirium harder to evaluate. (13)

If delirium is suspected, the first step should be to elicit the elements that define the disease. Clinicians who use the DSM-IV criteria at the bedside have a better chance of making an appropriate diagnosis. The patient’s state of awareness should be the focus of the initial examination. Patients should be checked for their degree of orientation and questioned on regular items to rule out any memory problems. Conversations can frequently indicate a chaotic cognitive process or be devoid of any content. If the doctor is unaware of the patient’s baseline mental health, family or carers can frequently convey information that may help in the patient’s evaluation. (14)

Laboratory, Imaging, and Other Studies to Consider in Delirium Diagnosis (15)

Basic laboratory evaluation, including:

- Full blood count (CBC): infection and severe anemia

- Serum electrolytes: Electrolyte imbalances, particularly hypernatremia and hyponatremia

- Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels: dehydration and occult renal failure (rare)

- Glucose: hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and hyperosmolar condition

- Liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase): occult choledocholithiasis, hepatic injury

-Workup for infectious diseases:

- Chest radiography: Pneumonia if fever or physical signs are present.

- Urinalysis and culture: Consider urinary tract infection when fever or other genitourinary symptoms are present.

- Lumbar puncture: If delirium is chronic, unexpected, or inexplicable, or occurs in younger individuals, there is a high suspicion of meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage based on history and physical examination.

– Myocardial infarction and arrhythmia on electrocardiogram

– Hypercarbia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Venous blood gases

– Drug concentrations: Some medicines might cause delirium even when serum levels are “normal.”

– Toxicology screening: If consumption is suspected, younger people are more likely to be affected.

– CT and MRI brain imaging: Based on the history and physical examination, there is a high likelihood of stroke or bleeding, or delirium is chronic, unexpected, or inexplicable, or happens in younger individuals.

– Electroencephalography: If an occult seizure is detected, it frequently exhibits diffuse slow-wave activity, although it is rarely useful in evaluating and treating reversible causes.

Management

The care of delirium patients must include many broad goals; some of which include ensuring the patient’s and staff’s safety, identifying, and treating the underlying causes, and improving the patient’s level of function.

Cognitive impairment, behavioral dyscontrol, and other delirium-related behavioral alterations can jeopardize the patient or medical personnel. The psychiatric consultant should constantly assess the risk of suicide, self-harm, and violence, and then create a plan to reduce these risks. Self-destructive or suicidal behavior can be caused by underlying cognitive dysfunction (along with sensory and perceptual impairment, hallucinations, or delusions). Furthermore, a patient may be impulsive and attempt to get out of bed, roam, and fall (which might result in serious damage or death) as well as remove IV lines, tubes, or catheters. Removal of potentially harmful things from the room and surrounding area, placement of sitters to offer more monitoring, use of physical restraints, and commencement of pharmacologic therapy are all frequently required.

Risk Factors

It is critical to identify triggering risk factors for delirium in order to apply prevention treatments to individuals who are most at risk. Several variables appear to contribute to the acute syndrome, and over 100 of them have been investigated for a possible relationship with an increased risk of developing delirium in the ICU. (17) These hazards may be divided into two categories: those that potentially predispose the patient to delirium (modifiable and nonmodifiable) and those that are connected to the care received in the ICU or the surroundings. (18)

Figure 2 Factors that predispose to and precipitate ICU delirium Delirium is caused by both baseline or predisposing, risk factors (on the top) and acquired, or precipitating, risk factors (on the bottom) (bottom). These may be changeable (on the left) or nonmodifiable (on the right) (right). ICU stands for intensive care unit.

Mart MF, et. Al Med. 2021;42(1):112-126. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1710572

Conclusion

Although delirium remains predominantly an acute-care concern, its significance for primary care, outpatient specialty, post – acute care, and long-term care physicians cannot be overstated. With the world’s population continuing to age, dementia and delirium will remain widespread health issues. Prompt detection of delirium and distinction from dementia will be critical in determining the appropriate therapy in the outpatient environment. Knowing when to refer patients for emergency or inpatient treatment is part of this differentiation. Similarly, learning to recognize protracted or subacute delirium in patients who have recently been hospitalized would be useful for outpatient physicians. As delirium research advances, physicians will be able to better avoid triggering variables such offending drugs while delivering more focused therapies to clear this critical geriatric condition.

References...