Article Title: Somatic Symptom Disorder

Author: Abdullah Jabeiti

Editor: Ahda Jbarah

Reviewer: Hassan Abushukair

Key words: Somatic, Psychiatry, Somatization

Introduction

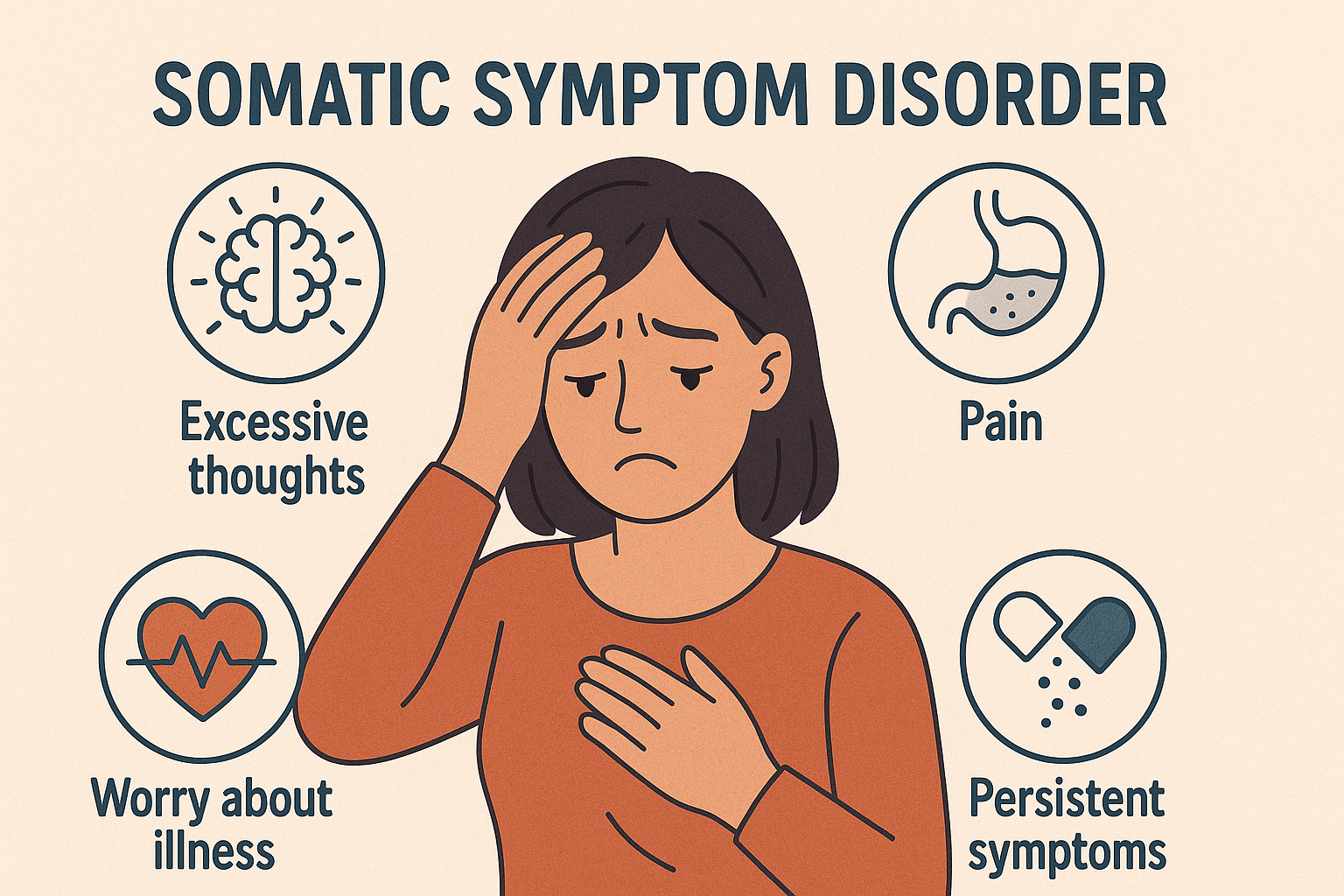

Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD), previously called Somatoform Disorder, is a condition characterized by the presence of one or more somatic symptoms (e.g., fatigue, abdominal pain, headache, etc.) that are unexplained by an organic disease process. Somatic Symptom Disorder Symptoms are accompanied by excessive thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors related to the symptom(s), causing the patient significant distress alongside social, individual, and/or occupational impairment. This diagnosis falls under the wider category of “Somatic Symptom Disorder and Related Disorders” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).

Brief History of Diagnosis

Somatic Symptom Disorder. Originally referred to as Briquet’s syndrome, which was first described by the physician Paul Briquet in 1859. He described these patients as having a constant feeling and worry of being sick, along with a multitude of symptoms attributable to several different organ systems. Even after countless consultations, investigations, and procedures that showed no proof of illness, the idea of illness and worry about the symptoms still persists. (1)

Epidemiology

SSD can occur in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood (2,3). Prevalence is estimated to be around 5-7% of the general population, with a higher predominance among females evidenced by a female-to-male ratio of 10:1 (2,3). Along with females, younger children tend to have a higher risk for somatization (4,5). Furthermore, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been found that individuals affected by the pandemic may have a high epidemiological burden of SSD, among many other mental health problems (6). Prevalence is also higher among patient groups with functional somatic syndromes, including fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue syndrome (7).

Etiology

Somatization can be a normative part of coping and development. It only becomes a disorder when it impairs several aspects of the patient’s daily life and meets specific criteria described in the DSM-5 (8). In terms of symptoms, there is no well-defined structural organic pathology that is explanatory for the symptoms experienced by the patient. And even if an organic pathology is present, the extent of symptoms and suffering they cause is still not explained, and treatment or remission of the underlying pathology does not alleviate the symptoms. This is partly the reason why the symptoms are referred to be functional in nature (9,10).

Although the disorder is suggested to stem from a heightened awareness of multiple bodily sensations mixed with the inclination to interpret these sensations as attributable to medical illness, the exact etiology still remains unclear (2). A study demonstrating the increased prevalence of both SSD and antisocial personality disorder among family members led to the belief that there might be genetic components influencing the development of both diseases (11). Another study with monozygotic and dizygotic twins showed evidence that genetic factors contributed to somatic symptoms by 7-21%, whereas the remaining was attributable to environmental factors (12).

Pathophysiology

SSD’s pathophysiology remains enigmatic. However, autonomic arousal from endogenous noradrenergic compounds has been implicated in causing gastric hypermotility, tachycardia, increased arousal, muscle tension, and pain associated with muscular hyperactivity in SSD patients (12).

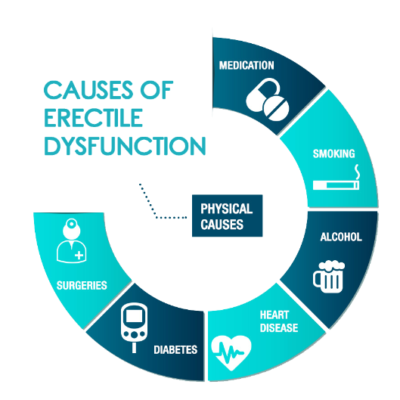

Risk Factors

As far as risk factors are involved, studies have proved childhood neglect, sexual abuse, a chaotic lifestyle, and history of alcohol and substance abuse as risk factors (2). Psychosocial stressors have also been implicated and include, but are not limited to, unemployment and impaired occupational functioning (3). Patients suffering from SSD also have higher rates of having a concurrent personality disorder, including histrionic, narcissistic, paranoid, borderline, antisocial, and avoidant personality disorders (13–16).

Clinical Presentation

Patients with SSD more commonly present to medical and primary care settings, rather than a psychiatric healthcare setting (8), with one or more somatic symptoms (most commonly pain) that cause them distress or impaired functioning. Patients also often have a rich history of futile medical visits, investigations and interventions with multiple physicians. They also demonstrate significant worry over the symptom(s) as excessive thoughts, feelings and/or behaviors revolving around their symptom(s) despite enough reassurance of not having any organic disease (8). In Children , the most common presenting symptoms are abdominal pain and headache, followed by back pain, limb pain, other neurologic symptoms and fatigue (4,5,8,17,18).

Diagnosis

Patients should undergo a thorough history with a full review of systems and a comprehensive physical exam to evaluate for physical causes of somatic complaints before considering the diagnosis of SSD. Since SSD is often comorbid with other psychiatric diseases, a mental status examination should be performed (19). Diagnostic criteria set by the DSM-5 are as follows (8):

- One or more somatic symptoms inducing distress, disturbance, and impairment of daily life.

- Excessive thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors related to the symptoms or the associated health concerns which manifest as one or more of the following:

- persistent thoughts disproportionate to the seriousness of symptoms

- persistent anxiety about health or symptoms

- excessive time and energy allocated to these symptoms

- Symptoms typically lasting for more than 6 months, even if a somatic symptom is not continuously present.

SSD specifiers include (8):

- If the SSD presents predominantly with pain (previously known as pain disorder)

- If it is persistent. To be considered persistent, the SSD course must have severe symptoms with significant impairment and a duration of more than 6 months

- If SSD is mild, moderate, or severe:

- Mild: only one of the criterion B symptoms is met

- Moderate: two or more of criterion B symptoms are met

- Severe: two or more of criterion B symptoms are met, as well as multiple somatic complaints (or one very severe somatic symptom)

Treatment

The main aim of treatment should be focused around building trust between the physician and the patient. Symptoms seem to improve when patients feel understood by their physicians or when they are satisfied with the explanation provided for their symptoms (20). For this reason, good physician-patient communication and relationship are often more important for the health of the patient than finding a somatic explanation (21). Thus, the primary care provider for such patients should schedule regular visits to reinforce the idea that the experienced symptoms are not indicative of a life-threatening or disabling medical condition and to avoid further unnecessary interventions (22).

Conversely, SSD can be managed through psychotherapy by cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or through pharmacologic approaches. Studies have shown that CBT is associated with significant improvement in functioning reported by patients and somatic symptoms, as well as a decrease in healthcare costs (23), and a reduction in depressive symptoms (24).

Any pharmacologic approach should be limited. However, antidepressants (SSRIs and SNRIs) can be initiated to treat relevant psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, and OCD since SSRIs and SNRIs have shown efficacy in SSD improvement compared to a placebo (25).

Prognosis

Longitudinal studies show that almost 90% of SSD cases last longer than 5 years (26,27). Around 50-75% of patients show improvement, whereas 10-30% deteriorate (28).