Article title: Dysembryoplastic Neuroepithelial Tumor (DNET)

Author: Samia Sulaiman

Editor: Miramar Haddad, Haneen A. Banihani

Reviewer: Lobana Mahdawi

Abbreviations

DNET: dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor

LEAT: long-term epilepsy-associated tumors

SGNE: specific glioneuronal element

GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein

PXA: pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma

Overview

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNETs), first elucidated in 1988 by Daumas-Duport, could be described as indolent, slow-growing, mixed neuronal-glial grade 1 neoplasm and are usually diagnosed in children and young adults and localized to the primary site of origin. [1]

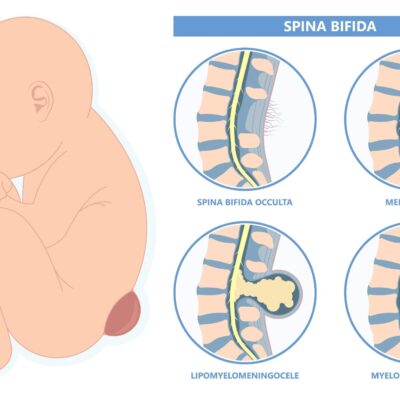

DNETs could arise from deep grey matter or cortical matter. In up to 80% of cases, they are frequently associated with cortical dysplasia, which accompanies unimodular or multinodular lesions. [2,5], they arise from secondary germinal layers and usually cause characteristic intractable focal seizures or may remain asymptomatic. [2, 18]

The etiologies and risk factors of DNETs are still poorly understood, yet ongoing research aims to develop a better understanding of DNETs and ease their diagnosis.[4]Researchers believe that a combination of genetic, environmental, and occupational factors may lead to the development of DNETs. [18]

This article will discuss the epidemiology, clinical presentation, histopathology, immunopathology, molecular pathology, diagnosis, and treatment and prognosis of DNETs.

Epidemiology

DNETs are comparatively rare as they amount to only 1-2% of all tumors and correspond to 13.5% of histological findings in children undergoing epilepsy surgery while contributing to 12% in adults undergoing epilepsy surgery.[4, 5]. Although nine years is the average age of diagnosis and despite it being mainly diagnosed in children and young adults, DNETs may still develop at any age.[4]

There has been a male predominance noticed in DNETs. [5] Furthermore, an association with Noonan syndrome, a genetic disorder characterized by developmental abnormalities, has been proposed. [2,3].

Clinical Presentation

Most patients present with a history of focal seizures that may or may not lead to hindered awareness and may progress to chronic drug-resistant epilepsy.[8] .This led to the introduction of the term “long-term epilepsy-associated tumors” (LEAT), which also includes other tumors.[9] . Furthermore, the symptoms accompanying DNETs depend on the location of the tumors.18 Therefore, the symptoms vary significantly among individuals, making diagnosing it rather difficult.[18] The most prominent symptom is persistent convulsions,[18] and other frequently observed symptoms of DNETs include:

-

- Chronic headaches

- Nausea and vomiting

- Numbness and tingling sensations

- Muscle weakness; weakness in arms and legs

- Neck pain

- Impaired vision, such as blurred vision, double vision, or poor eyesight

- Hearing impairment or hearing loss

- Speech problems

- Insomnia or loss of sleep, or excessive sleepiness (usually during daytime)

- Tremors

- Lack of coordination; unsteadiness and loss of balance (vertigo)

- Dizziness and fainting

- Confusion

- Changes in one’s behavior, personality changes

- Mental impairment

- Memory loss

- Seizures or convulsions, which may be any of the following types:

-

- Myoclonic seizures

- Grand mal (tonic-clonic) seizures

- Sensory seizures

- Complex partial seizures

The temporal lobe is the most common location where DNETs develop. Nevertheless, all CNS sites containing grey matter are still considered potential locations for DNETs to develop, as shown in Table 1.[2]

| Location | |

| Temporal Lobe | Over 65% of cases |

| Frontal Lobe | About 20% of cases |

| Caudate Nucleus | |

| Cerebellum | More commonly present with ataxia rather than seizures |

| Pons |

Table 1: Locations of DNETs in the brain and epidemiology involved with each location.[2]

Occasional presentation in the context of Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), a genetic disorder leading to the growth of tumors in nerve tissue, and XYY syndrome have been reported as well.[5,7]

Histopathology

Gross description:

DNETs may appear as expanded and elevated “macro gyri” that vary in size from millimeters to multiple centimeters.[5] .They may also sometimes appear with an exophytic component and demonstrate a heterogenous, gelatinous, cut surface with firmer tissue nodules upon sectioning.[2]. DNETs may also contain solid, mucoid, or cystic components.[6]

Microscopic (histologic) description:

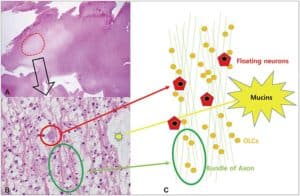

Characteristically, a specific glioneuronal element (SGNE) which refers to columnar bundles of axons surrounded by oligodendrocyte-like cells – oriented perpendicularly to the overlying cortical surface – is noticed. Floating neurons (mature ganglion cells) and stellate astrocytes between these columns are found in pools of mucin between columns, as shown in Figure 1.[2] .

Figure 1: A. Histological features of the multinodular pattern of DNETs. B: Glioneuronal elements with floating neurons. C: Diagram of the DNET architecture and components.8

There are three histological forms:[5]

-

- Simple form: SGNE only

- Complex form: SGNE with glial nodules and multinodular architecture

- Nonspecific form: no SGNE yet the same clinical and neuroimaging features as the complex form

The characteristic histological features of DNETs contributed to upgrading the term “long-term epilepsy-associated tumors” (LEAT) to introducing the more specific term “low-grade, developmental, epilepsy-associated” brain tumors.[8]

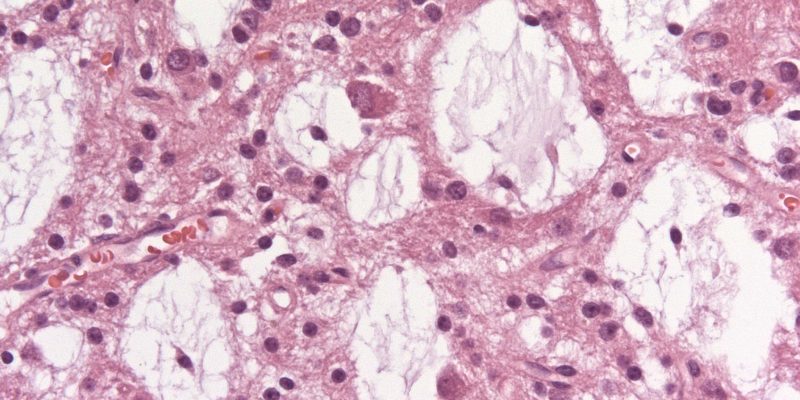

Immunohistochemistry

Alcian blue is positive for the extracellular component.[6] An astrocytic component is identified by the glial marker called glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) through immunostaining and is negative in oligodendroglial-like cells.[2]The oligodendrocyte-like cells are S100, OLIG2, and PDGFRA positive and may express myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and NOGO-A.2 The floating neurons are positive for NeuN.[6]

Moreover, negative stains include MAP2 in oligodendroglial-like cells in about 76.5% of cases.[6]

Molecular Pathology

Remarkably, DNETs do not show 1p19q co-deletion and are negative for IDH and TP53 mutations. These features are essential in distinguishing DNETs from oligodendrogliomas (IDH mutated and 1p19q co-deleted) and astrocytomas (typically IDH mutations).[2] The differential diagnosis of DNETs is further discussed later in this article.

In almost 30-50% of DNETs, BRAF V600E mutations have been noticed, yet it remains unclear whether BRAF V600E positivity and the presence of pilocytic astrocytoma are correlated in cases of DNETs.[5]. Moreover, when located outside of the cerebellum and shared by pilocytic astrocytomas, DNETs show fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase domain duplication (FGFR1-TKDD).[2]

Diagnosis

DNETs may remain undiagnosed for long periods as they are generally asymptomatic and slow growing. Diagnosis usually occurs when there is sudden worsening of symptoms, ongoing epileptic seizures at a young age, or upon radiological observation for unrelated health concerns. [18]

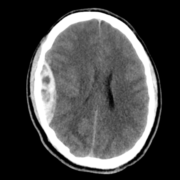

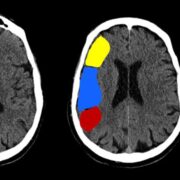

CT Scan

DNETs appear as low-density masses with no or slight enhancement. To an extent, the cranial fossa may be enlarged in some cases.In cortical DNETs, which is the typical case, the inner table of the skull vault appears to be remodeled yet with no erosion. Calcification is visible in about 30% of cases and typically seen in the deepest portions of the tumor, adjacent to the enhancing or hemorrhagic regions.[2] .This is shown in Figure 3.

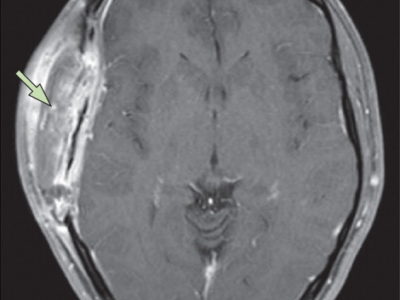

MRI

DNETs usually appear as cortical lesions, scarcely with any vasogenic edema .[5]

-

- T1: hypointense compared with adjacent brain2

- T1 C+ (Gd): 20-30% of cases show enhancement which could be heterogeneous or a mural nodule2

- T2: high signal “bubbly appearance”2

- T2/FLAIR: mixed-signal intensity with bright rim sign, partial suppression of “bubbles”2

- T2*: relatively frequent calcification, hemosiderin is uncommon as bleeding is only seen occasionally in DNETs2

- DWI: no restricted diffusion2

- MR spectroscopy: nonspecific, yet lactate may be present2

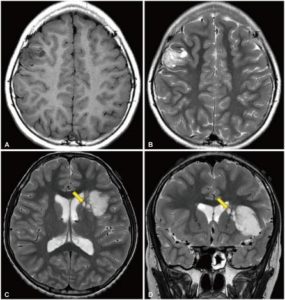

Figure 2: Radiological features of dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor. A and B: T1-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images of a 10-year-old girl who presented with recurrent focal seizures. In the right middle frontal gyrus, a multinodular mass is seen. C and D: T2-weighted axial and coronal images of a 12-year-old boy who presented with chronic epilepsy. A large tumor is positioned in the insular and left inferior frontal lobes. Several satellite lesions (shown with the yellow arrows) are seen on the medial side of the mass, in the caudate nucleus and internal capsule.8

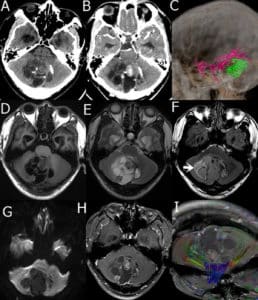

Figure 3: A 29-year-old male presented with a DNET in the cerebellar vermis. A: Plain CT scan of cerebellar vermis showing scattered calcification and low, slightly high mixed density; B: enhanced CT scan showed low-density areas without enhancement, solid nodules, septa, and cyst wall showed uneven enhancement; C: Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) branching arteries were noticed at the edge of tumors; D: T1WI tumor shows a low and iso-mixed signal on T1WI; E: T2WI tumor shows a high and iso- signal on T2WI; F. FLAIR tumor shows slightly hyperintensity, surrounded by high signal (arrow); G: DWI tumor shows low signal; H: Enhanced MRI the solid nodules, septa, and cyst walls were heterogeneously enhanced; I: DTI white matter fiber bundles were compressed and displaced.17

Differential Diagnosis

As DNETs may be challenging to diagnose, differential diagnosis is extremely significant. The main differential diagnosis is that in the features of another cortical tumor that make each distinctive from the other, as shown in Table 2.[2]

| Cortical tumor type | Characteristic features |

| Ganglioglioma |

– More common contrast enhancement – Calcification in about 50% of cases – Absence of a “bubbly” appearance |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma |

– Prominent contrast enhancement – Dural tail sign is seen often |

| Diffuse low-grade astrocytoma |

– IDH mutation – No SGNE |

| Oligodendroglioma |

– IDH mutated and 1p19q co-deleted – No SGNE |

| Desmoplastic infantile astrocytomas and ganglioglioma |

– Prominent dural involvement – Large, multiple lesions |

Table 2: Differential diagnosis of DNETs and cortical tumors according to distinguishing features[2]

Moreover, the differential diagnosis may also depend on the location of the tumor:

| Location | Condition | |

| Temporal lobe | Tumors (in order of decreasing frequency) |

– ganglioglioma – DNET – pilocytic astrocytoma – diffuse astrocytoma – oligodendroglioma – pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) |

| Cysts |

– neuroepithelial cyst – choroid fissural cyst |

|

| Other |

– herpes simplex encephalitis – mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS) – limbic encephalitis |

|

| Cortical | Tumors |

– ganglioglioma – low-grade astrocytoma – pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) – Taylor dysplasia oligoastrocytoma/oligodendroglioma |

Table 3: Differential diagnosis of DNETs according to the location in the brain [2]

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment is achieved through surgical resection to remove the tumor completely.[18] Irrespective of the extent of the seizures’ pharmacoresistance, surgery avoids the consequences of prolonged pharmacological therapy and the rare risk of malignant transformation.[12]

As the tumors are well-circumscribed and demonstrate essentially no growth over time, they are regarded benign and often completely removed safely. [2] No evidence of progression following subtotal resection or recurrence following total resection has been shown after long-term follow-up with patients.[5] However, in cases where the tumor recurs, it is generally recommended to undergo a second surgery to remove the tumor. [3] Seizures also frequently cease, even in patients undergoing incomplete resection.[2]

Radiation therapy may be used if tumor removal is not an option for specific patients or after surgery to destroy any remaining meningioma cells. Chemotherapy is not recommended except in higher-grade tumors. [18]

Complications

Possible complications related to DNETs include disability with undetected large tumors, severe memory loss, dementia, emotional and mental stress, problems with concentrations, peritumoral brain edema, and rarely, high-grade malignant transformation into anaplastic DNETs [18]

Possible surgical complications include wound infections, damage to muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and unaffected brain tissue during surgery, and rarely, tumor recurrence. [18]

Current Research

The development of malignancy and the pursuit of misinterpreting DNETs with other diagnoses, such as gangliogliomas, is currently being explored.[9] Moreover, complications, including intratumoral bleeding, are also being studied in voluminous tumors and in tumors that may undergo malignant transformation and have mutations such as FGFR1.[11]

Recent and extensive restructuring of DNET classification has also occurred in the past 5-10 years as genomic alterations are being further explored.[10]

In general, some predisposing factors and preventive measures associated with tumors are further discussed in the fifth article in the “Further Reading” list below.

Further Reading

-

- Volumetric growth analysis of an insular dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor over a 10-year follow-up

- Accuracy of distinguishing between dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors and other epileptogenic brain neoplasms with [¹¹C]methionine PET

- Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor: A rare brain tumor not to be misdiagnosed

- Association of CT and MRI Manifestations with Pathology in Dysembryoplastic Neuroepithelial Tumors

- Dysembryoplastic Neuroepithelial Tumor

- Rapidly growing dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor: case report.