Article topic: Hypertensive Cerebrovascular Disease: hyaline arteriolar sclerosis

Authors: Syrine Moughabghab, Sarah Al Mawla

Editors: Ahmad Safa, Joseph Akiki

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Hyaline, arteriolosclerosis, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension

Abstract

Hyaline arteriolosclerosis (HAS) of the brain is a vascular condition characterized by the accumulation of hyaline material in the walls of small cerebral arteries, leading to their thickening and luminal narrowing. The primary cause of brain HAS is chronic hypertension, which induces endothelial damage and plasma protein leakage into the arteriolar walls. Other contributing factors include diabetes mellitus, which exacerbates the severity of HAS. The pathogenesis involves plasma protein leakage, basement membrane component production, and the deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic hyaline material within the vessel walls, ultimately leading to reduced vessel compliance and ischemia. Diagnosis of brain HAS is primarily based on histological examination of brain tissue, with specific criteria including hyaline thickening without lipid deposits, inflammation, amyloid, or fibrinoid necrosis.

To ensure consistency, standardized scoring systems, such as those from the Vascular Cognitive Impairment Neuropathology Guidelines, are used to assess the severity of the condition and correlate findings with cognitive impairment. Treatment of HAS is challenging, as there are no specific therapies to reverse the condition. Therefore, management primarily focuses on preventing progression through controlling risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. However, Recent studies highlight the potential of stem cell therapy, particularly adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Ad-MSCs), to improve vascular function and reduce inflammation. Further Research is needed to validate these findings and establish standardized treatment protocols.

Overview

Arteriolosclerosis is the thickening of small artery walls due to the accumulation of intimal fibromuscular tissue or hyaline material [1]. There are two recognized subtypes of arteriolosclerosis: hyperplastic, marked by “onion-skinning” of the vessel wall, and hyaline, which involves a glassy, acellular thickening [2]. Hyaline arteriolosclerosis is a frequently occurring vascular disease, marked by the thickening of small artery walls and, often, an arteriolar lumen narrowing due to hyaline deposits [3]. This process is driven by plasma protein leakage within the subendothelial region, which sometimes extends into the media [4], and enhanced basement membrane component production by smooth muscle cells. Under electron microscopy, these deposits appear as marginally electron-dense, amorphous material within the vessel walls. It is a proteinaceous, eosinophilic substance that appears as a homogeneous, glassy material and primarily consists of precipitated plasma proteins, including the inactive form of C3b. This substance occurs within the walls of very small arteries, known as arterioles, particularly those lacking an internal elastic lamina, making it less common in small arteries [5].

Early Research on arteriolosclerosis predominantly focused on renal pathology. However, recent advancements have shifted focus to the brain, sparking significant interest among clinical and translational neuroscientists in understanding vascular pathology in this organ. Subsequently, brain arteriolosclerosis (B-ASC) has emerged as a common subtype of cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD), mainly found in older individuals and often associated with cognitive decline [2]. This paper will address cerebral hyaline arteriolosclerosis in detail, examining its risk factors, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment approaches, and recent developments in the field.

Epidemiology and risk factors

Hyaline arteriolosclerosis (HAS) is a common degenerative condition that significantly contributes to arterial vascular diseases, which are the leading cause of death in industrialized countries [1]. It most frequently affects the spleen and kidneys, although it is rarely seen in the heart or lungs. Other organs like the pancreas, adrenal glands, liver, intestines, brain, choroid, and retina can also be affected [6]. Key risk factors for HAS include aging, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. For instance, aging particularly impacts cerebral arterioles [4], becoming common in the spleen as early as a few months old and nearly universal in the elderly [6]. Whereas hypertension specifically increases HAS frequency in the kidneys [4]. Alternatively, diabetes mellitus exacerbates the prevalence and severity of HAS across multiple organs.

The presence of hypertension and diabetes accelerates the development of HAS, leading to earlier and more severe manifestations, especially in the kidneys. Furthermore, HAS is commonly observed in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), suggesting a potential link between the two conditions [7].

Etiology and pathogenesis

In a series of studies, Muirhead et al. suggested that arteriolar hyaline forms locally due to the necrosis of smooth muscle cells[6]. Concurrently, earlier Research reveals that hyaline arises from plasma components leaking into arteriolar walls due to hypertension-induced endothelial damage. Moreover, other investigators believe hyaline comprises basement membrane materials produced by the fusion of duplicated basal lamina from injured endothelial and smooth muscle cells. These processes collectively contribute to the thickening and stiffening of small vessels, leading to a persistent increase in peripheral resistance due to reduced vessel compliance and exacerbating ischemic effects [5].

The increase in hyaline arteriolosclerosis (HAS) frequency with age is often viewed as a “wear and tear” response or a natural part of aging. This process involves the gradual build-up of immune components like iC3b, Factor H, IgM, and classical C pathway elements within arteriolar walls, which is considered an unavoidable aspect of aging. This accumulation, along with the deposition of hyaline, leads to the atrophy of smooth muscle cells and the narrowing of the vessel lumen. In conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, arterioles become more permeable to macromolecules, which may further accelerate the development and severity of HAS by increasing hyaline deposition, contributing to vascular rigidity and reduced blood flow [6].

HAS and Hypertension

Hypertension and hyaline arteriolosclerosis (HAS) are closely linked, with numerous studies illustrating this connection. Initially, hypertension was considered a primary disease, independent of prior renal issues, as suggested by Fishberg in 1924. Subsequent Research, including work by Moritz and Oldt in 1937, established that HAS often arises as a primary pathological change in the renal arterioles, inevitably accompanied by hypertension. The development of HAS, especially in hypertensive patients, tends to be more severe and unrelated to age, unlike the mild forms seen in older individuals without hypertension. Furthermore, hypertension-related vascular lesions, such as fibrinoid necrosis, myointimal hyperplasia, and hyalinization of the media, underscore the significant role that persistent hypertension plays in the progression of HAS. These findings reinforce that HAS is a critical pathological consequence of sustained high blood pressure [5].

Narrowing of Arterioles Through Hyaline Build-Up

Arterioles are exposed to constant internal pressure of 20 mm Hg or more, which might suggest that degeneration would cause them to weaken and dilate. However, hyaline arteriolosclerosis presents a different scenario. Other than causing the vessel walls to break down and expand, this condition involves the accumulation of hyaline deposits within the arterioles. As a result, instead of dilating, the vessel walls become narrowed due to this substance build-up. These deposits form a coating on the inner surface of the vessel, which becomes integrated into the wall. Therefore, hyaline arteriolosclerosis is not a degenerative disease in the traditional sense but rather a condition where the narrowing of the arterioles is caused by the accumulation of hyaline rather than the breakdown of the vessel walls [3].

Molecular Mechanism in Arteriolar Hyaline

Studies have identified iC3b, a fragment of the complement protein C3, as a significant element of the hyaline deposits found in arterioles. Upon further investigation, Law et al. discovered that iC3b forms a covalent ester bond with the repeating disaccharide units of hyaluronic acid rather than with elastic or smooth muscle fibers, as these do not stain for C3. Consequently, the deposition of C3b in the arteriolar wall is attributed to this interaction, facilitated by the permeability of the endothelium to plasma proteins. However, the specific reason why C3b binds only to hyaluronic acid and not to other glycosaminoglycans remains unclear, possibly due to structural differences in the glycosaminoglycans [6].

Clinical presentation

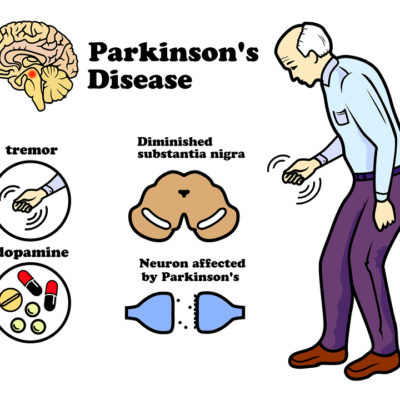

Cardiovascular conditions, such as atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis, are among the leading causes of mortality in developed nations, contributing significantly to sudden death, heart attacks, heart failure, strokes, kidney failure, and ischemic damage to limbs and vital organs [1]. However, hyaline arteriolosclerosis (HAS) typically has minimal pathophysiologic impact, except in the elderly and those with hypertension or diabetes mellitus. In such cases, significant hyaline thickening in the arteriolar walls causes pronounced narrowing of the vessel lumens and increased rigidity. This results in reduced blood flow and ischemic damage to essential functional units such as kidney nephrons, retinal cells in the eyes, neurons in the brain, and nerve fibers [6]. In the brain, clinical-pathologic Research reveals that brain arteriolosclerosis (B-ASC) is linked to declines in global cognition, episodic memory, working memory, and perceptual speed, as well as autonomic dysfunction and motor symptoms like Parkinsonism [2].

Workup and diagnosis

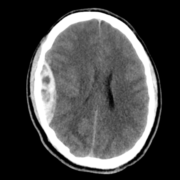

The Vascular Cognitive Impairment Neuropathology Guidelines (VCING) and the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Neuropathology (NACC NP) Data Set provide standardized approaches for diagnosing B-ASC, ensuring consistency in diagnosis and allows for reliable comparison across different studies and clinical settings. The diagnosis is primarily achieved through histological examination and standardized scoring:

A brain autopsy is performed, followed by staining the tissue samples that usually come from the occipital cortex white matter, with hematoxylin and eosin to visualize the abnormalities. The stained tissue is examined under a microscope to identify the presence of arteriolosclerosis using specific diagnostic criteria: a hyaline thickening of small blood vessels (less than 150 µm in diameter) without lipid deposits, inflammation, amyloid, or fibrinoid necrosis.

A semiquantitative severity scale is commonly used to quantify the extent of B-ASC. This scale categorizes the pathologic changes into levels such as “none” (representing normal vessels), “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe” (indicating severe hyaline fibrosis and lume) and stenosis). The reliability of the diagnosis is assessed, and the neuropathological findings are correlated with the patient’s clinical history. This correlation is evident as Research demonstrates a strong association between B-ASC and cognitive impairment, with individuals with dementia more frequently exhibiting B-ASC compared to those with normal cognitive status, underscoring the significance of the clinical-pathological association of B-ASC.”

This comprehensive approach helps establish a definitive diagnosis of B-ASC and shows inter-rater reliability among neuropathologists [2].

Treatment

Many approaches can be used to manage arteriosclerosis (ASC), including dietary adjustments, lifestyle changes, and cholesterol-lowering drugs. Statins are the most commonly prescribed medication for this condition, but they can have adverse effects.

Stem cell therapy

Recently, advances in stem cell technology have led to the development of new therapies for various diseases, including ASC. Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and, in particular, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Ad-MSC) have gained much attention due to their extremely low or no adverse reactions[8]. Long-term follow-up of patients with ischemic stroke who received MSC therapy showed some improvement with no adverse effects after five years. Moreover, a conditioned medium derived from the culture of such stem cells has also been used for therapy.

Ad-MSCs’ characteristics

Ad-MSCs possess pluripotent properties, meaning they can differentiate into various types of cells, such as adipocytes, myocytes, chondrocytes, and osteocytes. Inflammatory processes play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of ASC. d-MSCs possess potent anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, making them a potential therapeutic tool for treating arteriosclerosis.

Prevention

The Cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) is a commonly used indicator of arterial stiffness that is easy to examine. Improved CAVI levels resulting from AD-MSC treatment suggest that it prevented the development of atherosclerosis.

In a rodent study, MSCs prevented inflammatory and apoptotic processes in the brain by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the cerebrospinal fluid and periventricular brain region[1].

Also, MSCs modulated immune function by impairing the differentiation of dendritic cells, the primary antigen-presenting cells in human immunity. These findings underscore the importance of MSCs’ immunomodulatory function, which may also apply to the effect of Ad-MSC.

Risk factors

The primary risk factors typically associated with ASC are hypertension and diabetes. Additional comorbidities that increase the risk of brain arteriosclerosis (B-ASC) include obesity, renal failure, and disrupted sleep patterns [2].

Environmental factors, such as air pollution and chemical toxins, may promote B-ASC and exacerbate hypertension and other risk factors, as both epidemiological and animal studies demonstrate. However, multiple studies indicate that in elderly individuals, the risk factors typically linked to B-ASC show weaker correlations with B-ASC pathology compared to younger subjects.

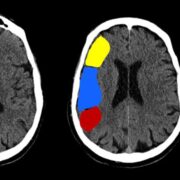

Hypertension poses a significant threat to global mortality and morbidity rates. Arteriolosclerosis is a complication arising from hypertension, as it involves narrowing the vessel lumens in both arteries and arterioles among hypertensive patients. Radiographic evidence of hypertension-induced brain injury includes the presence of white matter hyperintensity (WMH), small and large infarcts, enlarged perivascular spaces, and cerebral aneurysms.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) refers to a group of conditions that frequently occur together, including hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM), obesity, and dyslipidemia. Approximately one-third of American adults have MetS to some extent. etS has been linked to adverse effects on cognitive function, but the underlying mechanism requires further Research.

Several other conditions often cluster with MetS, including hyperhomocysteinemia and systemic inflammation. These conditions may have harmful synergistic effects on blood vessels, including the cerebral arterioles. For example, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, and dyslipidemia may each harm components of the cerebral vascular unit and contribute to B-ASC [2].

Studies by Arvanitakis et al. and Ighodaro et al. found that the association between hypertension and B-ASC was weaker in older adults. In another study of older participants, neither hypertension nor T2DM was significantly associated with B-ASC. These findings suggest that a significant proportion of elderly individuals’ B-ASC may be due to factors other than traditional MetS or cardiovascular risk factors. However, these studies and their conclusions should be interpreted carefully, considering potential confounding factors such as medicated diseases, death/survivor bias, racial disparities, differing risk factors in midlife and late life, and comorbid conditions.

B-ASC appears to be strongly influenced by both genetics and aging. One indication of this is the presence of substantial B-ASC in individuals under the age of 20 with “progeria,” a condition characterized by accelerated aging caused by specific gene mutations [2]. ASC has also been observed in aging wild-type animal species.

Different genetic risk factors affect individuals within distinct age ranges, and considerable focus has been placed on how aging, genetics, and various factors such as stress, diet, immune responses, and other processes that impact an individual’s lifespan influence the vasculature.

Chronological age consistently correlates with an increase in the prevalence of B-ASC in autopsy studies. For instance, Smith and colleagues found that cerebral small vessel disease was present in about 3% of individuals in their 40s but in nearly 19% of those aged 70. ASC increases even more dramatically among individuals over 80, with over 80% of those over 80 having identifiable B-ASC[2].

Prognosis:

Administration of Ad-MSC led to a significant improvement in high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and remnant-like particle cholesterol levels [8]. The treatment was found to be safe, and no adverse effects or toxicity were reported. This safety was attributed to using a proprietary, animal-origin-free medium for culturing the Ad-MSC, eliminating the risk of adverse immunoreactions and viral or infectious agent transmission.

Additionally, a recent report investigated the safety and efficacy of intravenous autologous Ad-MSC in a patient with acute myocardial infarction [8]. The results showed that Ad-MSC administration was safe and associated with improved recovery of left ventricular function, electrocardiographic findings, and serum brain natriuretic peptide levels. The authors concluded that Ad-MSC may be a promising therapeutic agent for diseases that conventional methods cannot treat.

In clinical studies, Gupta et al. (2013) demonstrated the efficacy of intramuscular administration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in treating lower limb arterial ischemia.

Recent Updates

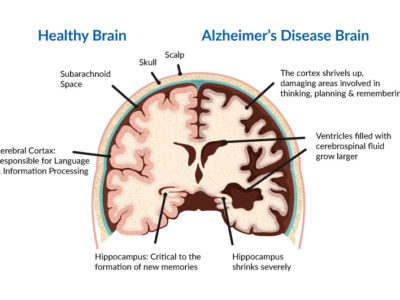

A recent study found that the apolipoprotein E gene ε4 allele (APOE-ε4) is a significant genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). ompared to the APOE-ε3/ε3 genotype, having at least one APOE-ε4 allele raises the risk of cognitive decline and dementia[9].

However, it is essential to note that the APOE alleles are also associated with a higher risk of cerebrovascular lesions, such as atherosclerosis, brain infarcts, hyaline arteriosclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy [9].

Conclusion

Managing hyaline arteriolosclerosis (HAS) of the brain remains challenging due to incomplete understanding of its pathogenesis and the lack of specific treatments. While chronic hypertension and diabetes are key risk factors, the precise mechanisms driving HAS are not fully detailed.

Effective management focuses on controlling these underlying conditions, highlighting the importance of prevention through rigorous control of hypertension and diabetes.

Future treatment prospects are promising, with recent studies investigating stem cell therapies, particularly adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Ad-MSCs), showing potential in improving vascular health and reducing inflammation. However, further research is required to confirm their efficacy and safety.

In summary, addressing the challenges of HAS involves ongoing Research to understand its mechanisms better and develop targeted therapies. Advances in treatment, such as stem cell therapy, offer hope for more effective management of this condition.