Article Topic: Millard Gubler Syndrome

Author: Sarkis Gerges

Editors: Odette El Ghawi , Joseph Akiki

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Millar Gubler Syndrome, ventral pontine syndrome, crossed hemiparesis

Abstract

Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) results from lesions in the pons, which impact the 7th cranial nerve and fibers from the corticospinal tract. It is typically associated with conditions such as brain tumors, hemorrhages, or infarctions. The hallmark of this syndrome is a crossed hemiparesis, where motor dysfunction affects the body on one side and the face on the opposite side. Diagnosis is primarily through neuroimaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) scans, which can identify pontine lesions and associated structural abnormalities. Treatment is focused on addressing the underlying cause of the pontine lesion, such as surgical intervention for tumors or medical management for hemorrhages and infarctions, alongside supportive therapies to manage motor and facial impairments.

Introduction

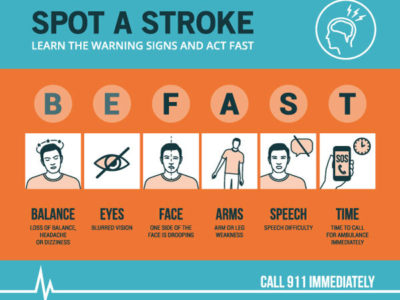

Pontine stroke is the most common brainstem stroke [1], accounting for 7% of all ischemic strokes [2]. Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS), also known as ventral pontine syndrome, is a rare condition characterized by ipsilateral eye abduction weakness, ipsilateral facial muscle weakness, and contralateral hemiparesis affecting the upper and lower extremities [3-5]. MGS results from a unilateral lesion in the basal portion of the caudal pons, typically caused by a mass, hemorrhage, demyelinating lesions, viral infections, or rarely, infarction [6,7].

Etiology and pathogenesis

Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) results from a lesion in the ventral part of the pons, which affects the cranial nerve fibers of the facial nerve (VII) and the transverse corticospinal tract. In addition, the abducens nerve, which travels through the medial pons to its ventral surface, is often involved.

MGS can arise from different causes depending on the age of the patient. In younger individuals, MGS is commonly associated with tumors, bacterial infections (such as neurocysticercosis and tuberculosis), viral infections (including rhombencephalitis), demyelinating diseases (like multiple sclerosis), and immune-related disorders such as neuro-Behçet’s disease [8-11].

In contrast, in older patients, MGS is primarily caused by vascular events, such as hemorrhage in the posterior circulation or ischemic stroke. Additionally, occlusion of pontine arteries, prepontine subarachnoid hematomas, or space-occupying lesions can lead to MGS [8-11].

Clinical Presentation

Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) presents with several key clinical manifestations.

Ipsilateral facial paralysis is a hallmark feature, characterized by weakness or paralysis of the facial muscles on the same side as the lesion, which affects both facial expression and the corneal reflex [16]. Additionally, contralateral hemiparesis occurs, resulting in weakness or paralysis of the limbs on the side opposite to the lesion due to involvement of the corticospinal tract [16]. Patients may also experience diplopia and restricted abduction, where difficulty moving the eye laterally and double vision are observed on the side of the lesion, stemming from abducens nerve involvement [1]. The Babinski sign, when present, usually indicates upper motor neuron damage on the affected side [6]. Although less common, rare sensory deficits may occasionally affect sensation in the face and extremities [4]. These symptoms collectively reflect the complex involvement of various cranial nerves and motor pathways in MGS.

Table 1 summarizes the anatomical structure affected in MGS and their corresponding clinical manifestations [4,5,14].

| Structure Involved | Signs and Symptoms |

| Corticospinal tract | Contralateral hemiplegia |

| Abducent nerve (CN VI) | Ipsilateral paralysis of lateral rectus muscle |

| Facial nerve (CN VII) | Ipsilateral paresis of muscles of the face and loss of corneal reflex |

Complications

The main complications of Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) encompass a range of symptoms linked to the underlying brainstem pathology:

- Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS): This condition, characterized by an uncontrollable urge to move the legs, can occur as a complication of a brainstem stroke, particularly a pontine stroke. The pathophysiology of RLS in the context of MGS is associated with the disruption of dopaminergic pathways in the brainstem, which can affect the motor control and sensory pathways involved in RLS [17].

- Atypical Facial or Orbital Pain: Patients with MGS may experience facial or orbital pain, which is atypical but not uncommon in cases of pontine stroke. This pain often results from the involvement of cranial nerves in the pontine region, leading to neuropathic pain or dysesthesia in the face or around the eyes [18].

- Emotional Dysmetria: This symptom is generally associated with cerebellar involvement, which can occur in conjunction with MGS due to its impact on the brainstem structures. Emotional dysmetria involves difficulties in regulating emotional responses and can affect emotional control and behavior, reflecting the cerebellum’s role in emotional and cognitive processing [19].

These complications arise due to the intricate connections between the pons, cerebellum, and other brainstem regions, highlighting the multifaceted impact of lesions in this area.

Workup and Diagnosis

The diagnostic workup for Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) involves a comprehensive approach to identify the underlying cause and assess the extent of neurological damage.

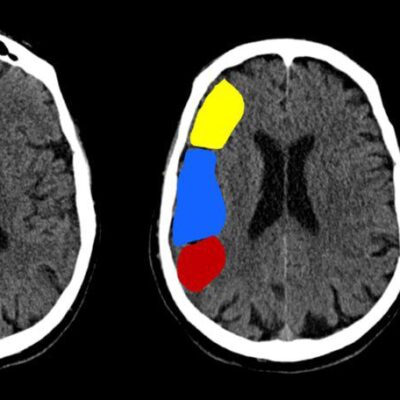

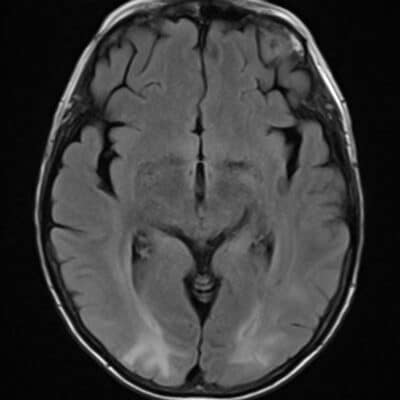

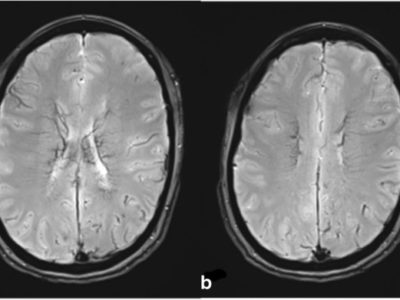

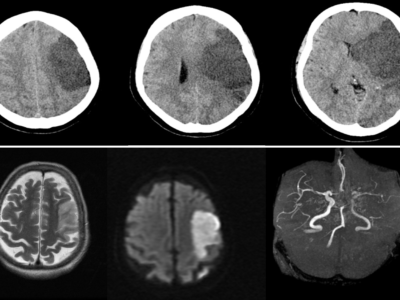

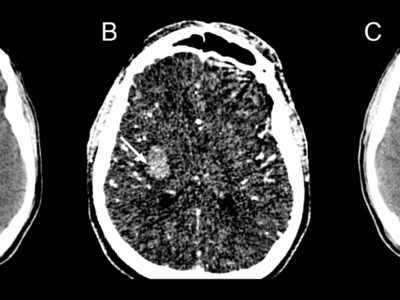

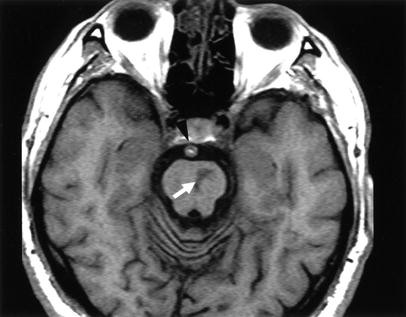

Initial imaging often includes non-contrast computed tomography (CT), which is used as a preliminary step to detect acute hemorrhages or structural abnormalities, especially if a cerebrovascular cause is suspected [20]. While CT is useful for identifying acute blood products, it is generally supplemented by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for more detailed evaluation. MRI is more sensitive than CT in detecting brainstem lesions, making it crucial for a thorough assessment [21]. Figure 1 shows an MRI of a patient diagnosed with Millard Gubler demonstrating an infarct in the left side of the ventral pons [25]. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is employed to identify occlusions or ischemic areas, aiding in the evaluation of vascular causes [22].

MR imaging revealing an infarct in the left side of the ventral pons in a patient diagnosed with Millard Gubler [25].

Blood tests are performed to identify underlying conditions such as infections, inflammatory responses, or coagulopathies, with common tests including complete blood count (CBC) and blood chemistry [23]. Blood cultures and serological tests help identify specific pathogens if an infectious etiology is considered. A lumbar puncture may be conducted to analyze cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for signs of infection, inflammation, or malignancy, which can be particularly helpful if a demyelinating or infectious cause is suspected [24]. Electroencephalography (EEG) is used to detect abnormal brain electrical activity that may indicate seizures or other neurological conditions. Additionally, electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies can assess peripheral nerve and muscle integrity, which aids in distinguishing central from peripheral causes of neurological symptoms.

These combined diagnostic approaches provide a comprehensive evaluation to guide the effective treatment and management of MGS.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) encompasses several crossed brainstem syndromes, each presenting with distinct clinical features that can overlap with those of MGS. Understanding these syndromes is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

Foville Syndrome

This syndrome results from lesions in the pontine tegmentum, particularly affecting the facial nerve and abducens nerve. It is characterized by ipsilateral facial paralysis, ipsilateral abducens nerve palsy leading to horizontal gaze impairment, and contralateral hemiparesis due to corticospinal tract involvement [11].

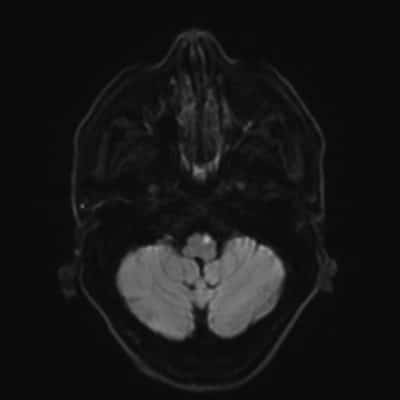

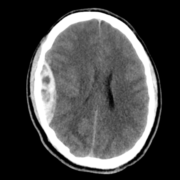

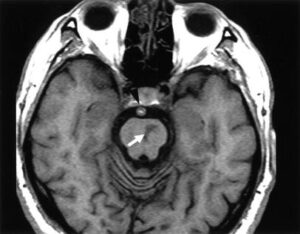

![Acute infarct showing restricted diffusion is noted involving right half of pons in a patient diagnosed with Foville Syndrome [12].](https://neuropedia.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/radiopedia-214x300.png)

Figure 1: Acute infarct showing restricted diffusion is noted involving the right half of pons in a patient diagnosed with Foville Syndrome [12].

Raymond Syndrome

Caused by lesions in the lower pons affecting the abducens nerve and the corticospinal tract, Raymond Syndrome presents with ipsilateral abducens nerve palsy resulting in horizontal gaze difficulty and contralateral hemiparesis [22].

Raymond-Cestan Syndrome

This syndrome combines features of Raymond Syndrome with additional involvement of the pontine tegmentum. It results in ipsilateral facial weakness, contralateral hemiparesis, and dysarthria due to damage to the pontine nuclei and corticospinal tract [23].

Gellé Syndrome

Characterized by lesions affecting the abducens nerve and the facial nerve, Gellé Syndrome presents with ipsilateral facial weakness, contralateral hemiparesis, and ataxia due to involvement of the pontine tegmentum and cerebellum [23].

Brissaud-Sicard Syndrome

This syndrome results from lesions affecting the ventral pons, leading to ipsilateral facial paralysis, contralateral hemiparesis, and occasionally dysarthria. The presentation overlaps with that of MGS but lacks the specific features of facial nerve involvement [11].

Gasperini Syndrome

Gasperini Syndrome involves lesions in the pons causing facial nerve paralysis, contralateral hemiparesis, and potentially dysphagia and dysarthria due to the involvement of the pontine structures and adjacent brainstem areas [21].

Differentiating these syndromes from MGS requires careful clinical evaluation and imaging studies to identify the specific location and extent of brainstem lesions.

Treatment and management

Treatment for Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) centers on addressing the underlying cause while providing supportive care to manage symptoms effectively.

If MGS is caused by a tumor, treatment options may include surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy to manage the tumor and relieve pressure on the affected area [24]. For MGS resulting from a stroke, interventions such as thrombolysis or clot extraction may be considered to address the ischemic event [24]. Supportive care plays a crucial role in symptom management, with physical and occupational therapy aimed at improving functional outcomes and enhancing quality of life [24]. Additionally, management of ophthalmic symptoms may involve strabismus surgery to correct diplopia and botulinum toxin injections to the levator palpebrae superioris muscle to address the loss of corneal reflex [20].

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with Millard-Gubler Syndrome (MGS) is heavily influenced by the underlying cause and the extent of brainstem damage. The severity and recovery of MGS largely depend on the initial etiology, such as whether the syndrome results from a tumor, stroke, or other conditions affecting the pons. For instance, if MGS is caused by a mass lesion or tumor, the prognosis will be influenced by the effectiveness of surgical resection or other tumor management strategies. Similarly, for MGS resulting from hemorrhage or ischemic stroke, the outcomes are contingent upon the extent of the lesion and the timeliness of medical interventions.

In particular, isolated pontine infarctions can have a more favorable prognosis if they are diagnosed and managed promptly. Early intervention, including thrombolysis for ischemic events or appropriate management for hemorrhagic strokes, can significantly impact recovery and functional outcomes. The extent of brainstem injury also plays a critical role in determining recovery; less severe injuries may lead to better functional recovery and reduced long-term disability.

Overall, prognosis is individualized, and early diagnosis, along with tailored treatment strategies, can improve the likelihood of a favorable outcome for patients with MGS [2].