Article Title: Aphasia

Author: Alaa Amer

Editors: Hamid Ghanem, Peter Bael

Reviewer: Zain Alsaddi

Keywords: Aphasia, Broca’s, Wernicke’s, Neurological Language Disorder, Stroke-induced aphasia, Progressive Aphasia, Acquired Aphasia.

Overview

Aphasia refers to a disorder of language formation due to damage in specific brain regions that control language expression and comprehension. Researchers classified aphasia according to the assessment of language functions such as auditory comprehension, spontaneous speech, reading and writing, repetition, and naming. Speech, language therapy, and pharmaceutical therapy are two approaches to treat aphasia.

Introduction

Aphasia is a term borrowed from the French term “aphasie” and the Greek term “phásis”, where “a” means “not” and “phásis” means “to say, speak”. Hence aphasia, linguistically, means speechless. In medical practice, it represents disturbances of language expression and comprehension in any modality, whether through writing, speech, or linguistic signing. 1,2

Aphasia patients can’t convert nonverbal thoughts into grammatical organization and symbols that form language accurately. The spontaneous speech of patients diagnosed with aphasia is nearly always impaired, resulting in difficulty understanding their verbal output due to language problems such as incorrect sentence formation, omitted words, and paraphasia. furthermore, aphasia happens in relation to both auditory signal languages and visual motor signs (sign language). 3

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Aphasia represents a profoundly devastating outcome arising from damage to the brain’s dominant hemisphere, where the language center resides, whether caused by structural or functional impairments. The left hemisphere is the dominant hemisphere in 95–99% of right-handed people and in 70% of left-handed people. One comprehensive study delved into the hemisphere lateralization of language by examining a cohort of 75 individuals, consisting of 37 right-handed and 38 left-handed participants. Researchers found that 97% of right-handers have left-hemisphere dominance, while the remaining 3% have Right-hemisphere dominance. it further showed that 74% of left-handed subjects have left hemisphere dominance, and 26% have right hemisphere dominance. 4,22

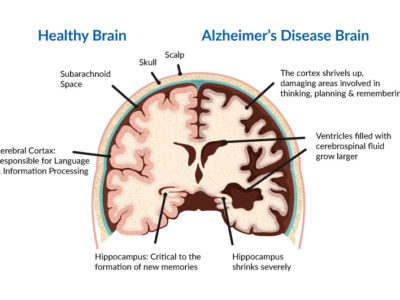

Any disease or abnormal condition affecting the areas of language can cause aphasia. While aphasia is most prevalent in patients who have suffered from a stroke or a cerebrovascular disease, it also can be seen in patients with brain tumors, infections, and traumatic brain injury. Furthermore, vascular dementia, Pick’s disease (frontotemporal dementia), Alzheimer’s, and various neurodegenerative conditions can induce aphasia through their relentless and progressive degradation of brain tissues. Additionally, it can arise from other cerebral irregularities, including metabolic, nutritional, and developmental disorders. Aphasia may also be linked to conditions stemming from drug use or exposure to chemical agents 2,5,6

Classification of aphasia

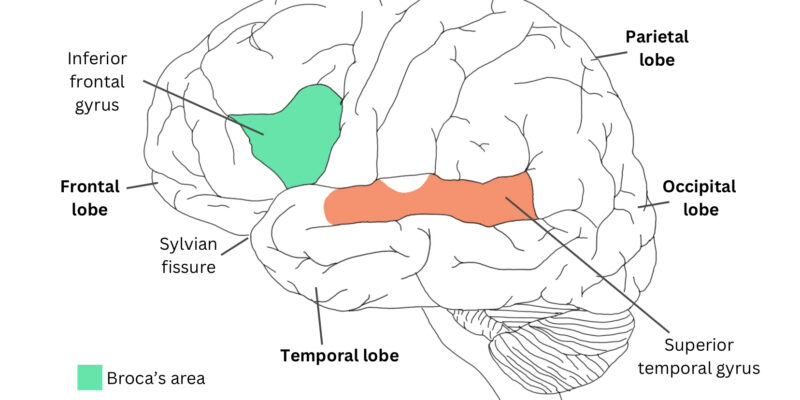

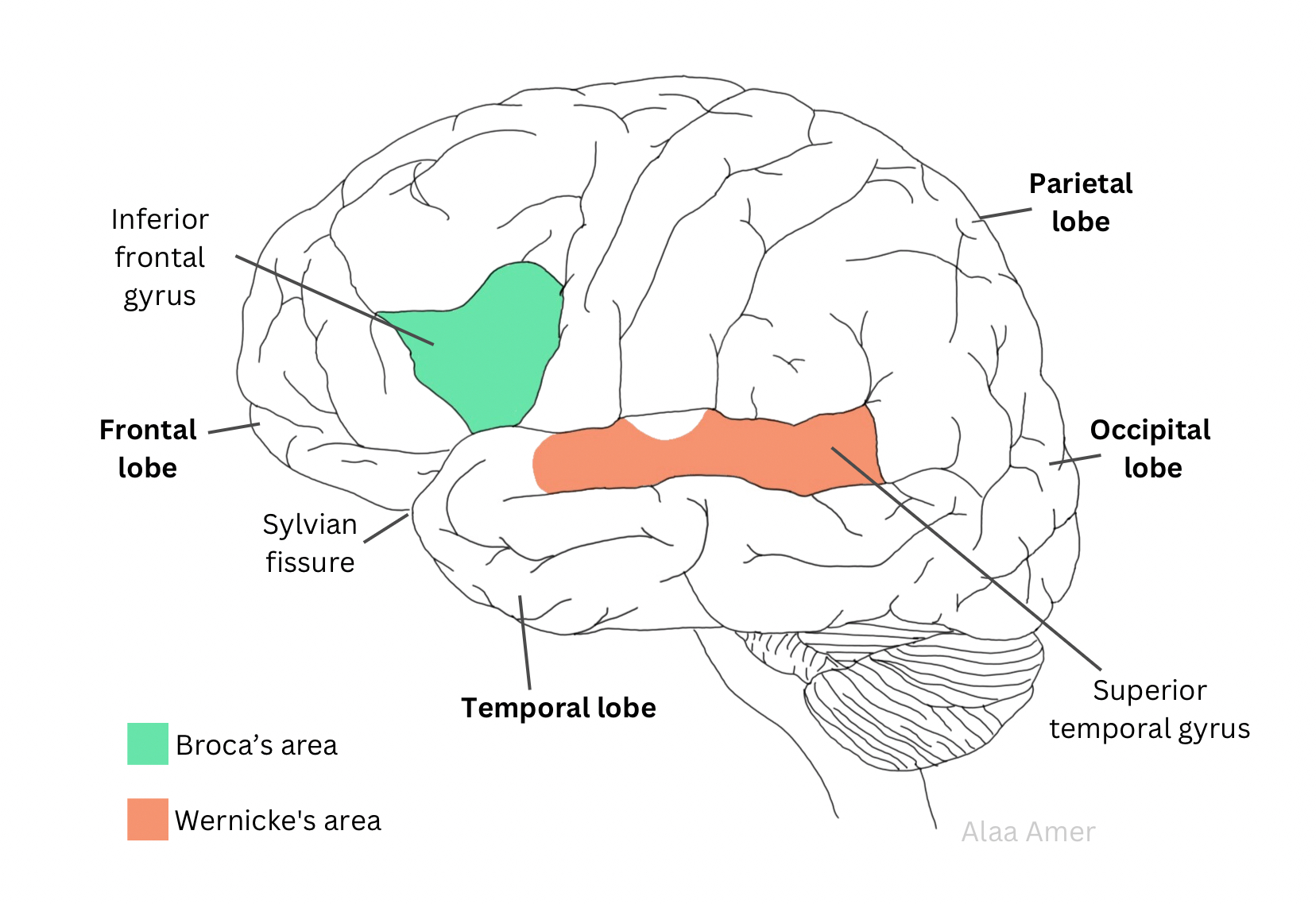

Figure 1: Shows the location of Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area.8

- Broca’s aphasia

As shown in Figure 1, the Broca’s area lies posteriorly in the inferior frontal gyrus. It facilitates the fluent expression of language, enabling the precise sequencing of words, construction of grammatical structures, and comprehension of grammar. 7

Broca’s aphasia, also known as fluent aphasia, involves the Broca’s area and it is a primary deficit in language, output or speech production, with a relatively preserved comprehension. The spectrum of deficits spans a broad spectrum, ranging from the subtlest form of speech impoverishment (cortical dysarthria), where comprehension and writing abilities remain wholly intact, to a total absence of phonetic, linguistic, and gestural communication.8

The clinical manifestations of Broca’s aphasia include impaired fluency, which can range from extreme cases of near-silence or the production of vowel-like sounds to less severe instances where speech lacks essential elements like conjunctions (or, and, but), prepositions (on, to, in), plurals, verb tenses, and auxiliary verbs. The latter results in a form of speech known as “telegraphic speech”. Other cases may experience a lack of flow of speech, paraphasic errors, and halting. Another aspect is impaired repetition. Alongside these linguistic impairments, there are associated physical signs such as weakness of the right arm and face and apraxia of speech. Notably, comprehension in individuals with Broca’s aphasia remains relatively intact, although there may be occasional difficulties in understanding sentences with complex syntax and grammar.7

- Wernicke’s aphasia

Wernicke’s area lies posteriorly in the superior temporal gyrus. It’s responsible for the processing of language input and comprehension; therefore, patients with Wernicke’s aphasia find it hard to comprehend language.

Also referred to as “fluent, sensory afferent, and receptive aphasia”, Wernicke’s aphasia presents with distinct clinical features; In terms of fluency, individuals with this condition exhibit fluent but paraphasic speech. In contrast to Broca’s aphasia, patients with Wernicke’s aphasia speak volubly and gesture freely, seemingly unaware of their speech difficulties. However, despite this fluency, the content of their speech lacks coherent meaning.7

Verbal paraphasia is the substitution of one word for another and it is a prominent hallmark of this condition. For example, they might say “The grass is yellow” when referring to a completely unrelated topic. Additionally, repetition abilities are impaired; in terms of comprehension, patients with Wernicke’s aphasia encounter significant challenges in understanding both spoken and sign languages. Localization of the affected areas within the brain includes temporal, infra-sylvian, angular, and supramarginal gyri.7,8

- Global aphasia

Global aphasia combines the deficits of Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia. One can distinguish Global aphasia by a nearly absolute loss of language comprehension or speech formulation. Spontaneous speech, repetition, and naming might be impaired. Global aphasia is the most common type of aphasia in patients who have suffered from strokes. Among the majority of patients, comprehension recovers well, leading to a change from global to Broca’s aphasia.9,10

In this type of aphasia, the damage usually involves most of the left middle cerebral artery area. More infrequently, involving the entire peri-sylvian area of the left hemisphere (parietal, temporal, and frontal areas).10

- Conduction aphasia

Conduction aphasia is not common. In theory, it’s a crucial syndrome that can be remembered by its noticeable repetition disturbances.

Conduction aphasia primarily stems from damage to the arcuate fasciculus. While many individuals exhibit spontaneous speech, some notably produce literal paraphasic errors and experience hesitation as they strive for self-correction. Despite this condition, comprehension remains intact in conduction aphasia, yet difficulties in naming can manifest. Associated deficits include hemianopia, usually mild or absent hemiparesis, right-sided sensory loss, and some patients may have limb apraxia.8,9

- Anomic aphasia

This condition describes the aphasic syndrome in which naming is the principal deficit. Speech is normal and spontaneous, reading, repetition, and comprehension are undamaged. Anomic aphasia is common; however, its localization is less specific than other aphasias.8 - Transcortical Aphasias

Transcortical Aphasias describe syndromes where the lesion damages the connections from other cortical centers into the language circuit. In this type of aphasia, repetition is intact.8

Transcortical Aphasias include: (Table 1)

- Transcortical motor aphasia.

- Transcortical sensory aphasia.

- Mixed transcortical aphasia, also known as isolation syndrome.

| Feature | Transcortical motor | Transcortical sensory | Isolation syndrome |

| Speech | Non-fluent | Fluent, echolalic | Nonfluent, echolalic |

| Comprehension | Intact | Impaired | Impaired |

| Reading | Intact | Impaired | Impaired |

| Writing | Intact | Impaired | Impaired |

| Naming | Impaired | Impaired | Impaired |

| Repetition | Intact | Intact | Intact |

Table 1. Shows Bedside Features of Transcortical Aphasias.8

Diagnosing Aphasia

To reach achievable treatment goals, conducting a full assessment is a crucial step toward diagnosis. To begin, it’s important to get an accurate patient history, including demographic data (age, occupation, marital status, etc.), background medical information, cultural background, and others. Obtaining a complete understanding of how the impairments have restricted the patient’s social activities and overall daily life is the main aim of aphasia assessment.11

Assessment of Aphasia should also include every component of language (semantics, syntax) in every manner (using and comprehending spoken language, written language, and gestures). Open-ended questions and pictures description helps in assessing spontaneous speech quality and fluency, it’s necessary to assess the reliability of yes-or-no responses. One should evaluate naming by using confrontation naming assessment. Moreover, assessment of auditory comprehension is a must, including sentences (simple and complex), single words, and commands that include multi-steps.11

Other tests that can be used to diagnose aphasia include the most common comprehensive aphasia assessments which are the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE) and the Western Aphasia Battery Revised (WAB-R). Both assessments enable specialists to categorize patients according to their specific aphasia types. The BDAE test includes assessments of spontaneous speech, reading, writing, and repetition. Likewise, the WAR-R evaluates spoken language formulation and comprehension, writing and reading, and praxis.12,13

The Comprehensive Aphasia Test (CAT) doesn’t directly categorize patients into aphasia types. It’s necessary to follow up on the aphasia assessment with other tests containing specific cognitive and linguistic deficits. Tests like the Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences (NAVS) and the Psycholinguistic Assessment of Language Processing in Aphasia (PALPA) offer more specific insights needed for accurate classification.14,15

Treatment of aphasia

- Behavioral approaches

The management of Aphasia relies on various factors like patient treatment end goals, specific limitations, and delivery models. Behavioral approaches include compensatory approaches that focus on activities, restorative approaches that focus on body structures, functional approaches that work on daily life treatment, and other approaches that anchor on training particular deficits of language including Melodic Intonation Therapy (MIT) and Constraint-Induced Language Therapy (CILT).

Behavioral therapy also includes Life Participation Approach to Aphasia (LPAA), Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST), Semantic Feature Analysis (SFA), and Treatment of Underlying Forms (TUF).11,16

- Pharmacological treatment

Clinicians have used pharmacological therapy to treat post-stroke aphasia for decades, but recently, there has been a focus on using pharmacological agents to enhance language skills. This approach primarily focuses on strengthening language and cognitive functions associated with language, encompassing memory, attention, and the acquisition of vocabulary. Pharmacological agents can be used with speech and language therapy together to improve the outcomes of the treatment, or they can be used alone as a sole treatment. The main drug classes that researchers investigate for treating aphasia are cholinergic, nootropic, serotonergic, and catecholaminergic. Bromocriptine is a catecholaminergic drug. It has positive effects on treating aphasias, especially in chronic non-fluent aphasias.11,17

Donepezil is the most commonly used cholinergic drug for treating aphasia. It belongs to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and it’s also commonly used to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers found that donepezil improved naming, comprehension as well as spontaneous speech, particularly in chronic post-stroke aphasia patients.17

Other drugs used for treating aphasia include piracetam. It’s a nootropic agent and acts on the initial phase of the stroke. Moreover, memantine is a drug that belongs to the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists.18

Moreover, Serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluvoxamine have shown remarkable improvements in naming and mood. Depression poses a challenge as it not only impairs language performance but also diminishes patients’ motivation to engage in speech and language therapy. A recent study indicated that individuals with damage to the superior longitudinal fasciculus and/or posterior superior temporal gyrus when administered SSRIs post-stroke for three months, experienced improved naming outcomes.19,20

- Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) therapy

Advancements in neuro-imaging technology help with the activation of language areas in the brain. NIBS therapy includes transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to improve the recovery of aphasia.21

References...