Article topic: Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

Author: Ihda Mahmoud Bani Khalaf

Editor: Sadeen Eid

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Obstructive, Sleep Disorder, Apnea, Psychiatry

Overview

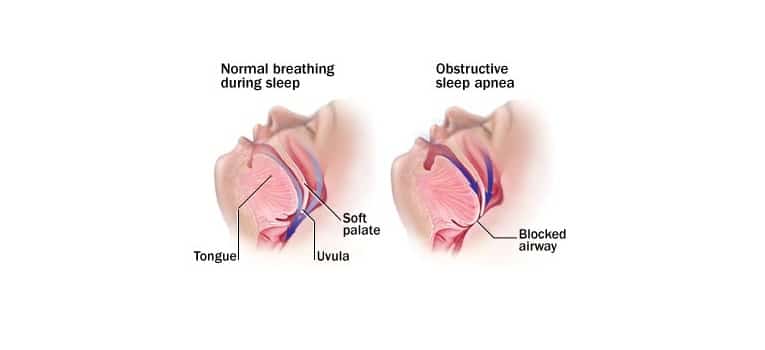

A sleep disorder called obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by frequent episodes of the airway becoming completely or partially blocked while a person is asleep. (1) It happens when there are frequent episodes of upper airway obstruction and collapses while you’re sleeping coupled with arousals that may or may not cause oxygen desaturations. The oropharynx in the back of the throat collapses as a result of these OSA events, causing arousal, oxygen desaturation, or both, leading to fragmented sleep. (1)

Studies show that OSA is common. According to a 2015 study conducted in Switzerland, 23% of women and 50% of men had at least moderate OSA. (2) According to the Sleep Heart Health study from 2002, 9% of women and 24% of men have OSA that is at least mild. (3) According to the Wisconsin Sleep Study Cohort, 17% of men and 9% of women who are between the ages of 50 and 70 have at least moderate OSA, compared to 10% of men and 3% of women in that age group. (4) In the United States, it is estimated that 82% of men and 93% of women have OSA but are not yet diagnosed. (5)

Although patients differ in the number and combination of symptoms they report, there are a number of typical sleep and daytime symptoms linked to OSA (Table 1). (6) Snoring is one of the most typical sleep-related symptoms. Excessive daytime sleepiness or fatigue are common OSA daytime symptoms. While fatigue refers to feeling worn out, low on energy, and unmotivated, excessive daytime sleepiness refers to feeling very drowsy or very sleepy at times. Another sign is feeling exhausted despite getting the recommended 7 to 9 hours of sleep.

| Sleep | Daytime |

| Snoring | Excessive sleepiness |

| Gasping | Fatigue |

| Snorting | Morning headaches |

| Not breathing | Memory or concentration issues |

| Fragmented sleep | Mood disturbances or irritability |

| Sleep maintenance insomnia (inability to stay asleep or wake and not returning to sleep) | Decreased libido |

| Nocturia | |

| Bedwetting | |

| Night sweats |

Table 1: obstructive sleep apnea symptoms (6)

Epidemiology

Around the world, Obstructive sleep apnea is very common. (7) Furthermore, some recent studies even point to an increase in prevalence, which is likely due to the rising prevalence of overweight and obese people. (7) Updated population prevalence estimates based on long-term data from the Wisconsin cohort study do in fact lend credence to this idea. When compared to 5% of men and 4% of women in 1993, 13% of men and 6% of women in the 30-70 age range had moderate to severe sleep-disordered breathing in the late 2000s (apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) 15). (4) The authors came to the conclusion that there had been a 14-55% increase in the prevalence of OSA since the early 1990s, depending on the age and gender subgroup.

The ratio is typically even higher in populations of sleep clinics, (8) despite the fact that Obstructive Sleep Apnea is typically two to three times more common in men than in women in studies of the general population. Uncertainty about the cause of this disparity suggests that it may be due to the different symptom profiles that cause men to seek medical care earlier than women. Health professionals may also underdiagnose certain subgroups, such as premenopausal women, young and lean people, and patients without severe snoring or obvious Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS). (9)

Etiology and Pathogeneses

Some pathophysiological factors, such as increased upper airway collapsibility, a narrower upper airway, and skeletal abnormalities, are prevalent in both adult and pediatric OSA. Despite these factors, there might be various etiological factors that contribute to the disease. (10)

The peak of incidence occurs between the ages of 2 and 5 years in preschoolers, which is also the time when the adenoids and tonsils develop most in comparison to the oro-pharyngeal space. (11) There is no direct correlation between the size of the adenoids and tonsils and the severity of respiratory sleep disorder, despite the fact that adenotonsillar hypertrophy is a significant risk factor for pediatric OSA. (12) Specifically in the second childhood (6–9 years) and during adolescence, obesity is becoming a more significant and frequent risk factor for pediatric OSA. (13)

Risk factors

Both non-modifiable and modifiable factors affect the risk of OSA. Risk factors that cannot be changed include race, age, and male sex. A higher risk of OSA may be caused by cranial facial anatomy that results in narrow airways, genetic predisposition, a family history of OSA, or both. Obesity, drugs that relax muscles and narrow the airway (opioids, benzodiazepines, alcohol), endocrine conditions (hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome), smoking, nasal congestion, or obstruction are all modifiable risk factors. (9)

Sex

Men have a higher risk of developing OSA than women, though once a woman enters menopause, her risk approaches that of men. It was discovered that postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy had lower rates of OSA, indicating that a loss of hormones increases the risk of OSA. (14,15) Women also have more OSA during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and less OSA when sleeping supine, whereas most men have OSA when sleeping supine. (8,16) Women with similar body mass indexes (BMI) have OSA that is less severe than men. (8) Men and women experience different symptoms; men are more likely to snore and have witnessed apneas, while women are more likely to experience insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness. (8) This could explain the higher mortality rate in women and the delayed diagnosis in men.

Age

Age increases the risk of OSA. The prevalence of moderate OSA was 23% in men under the age of 72 and 30% in men over the age of 80 in a study of men aged 65 or older. (17) In contrast, 10% of men between the ages of 30 and 40 had moderate OSA. (4) Age-related decline in slow wave sleep, or deep sleep, which protects against sleep-disordered breathing and airway collapse, may be the cause of an increased risk of OSA. (18) Additionally, older adults report less daytime fatigue and sleepiness. (19)

Race

Blacks (20%) and American Indians (23%) had a slightly higher risk of moderate to severe OSA than did whites (17%), according to the Sleep Heart Health Study. (3) According to a different study, the prevalence of OSA was 30% in white people, 32% in black people, 38% in Hispanic people, and 39% in Chinese people. (20) Although another study found no racial differences in older patients, (21) it was reported that young blacks ( 25 years) had a higher prevalence of OSA than whites. (22) These variations in craniofacial anatomy may be the cause of these racial differences.

Obesity

Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) and its correlates of a higher waist-to-hip ratio and neck circumference are associated with an increased risk of OSA. (3) In comparison to a 10% weight loss, a 10% increase in body weight causes a six-fold increase in moderate to severe OSA and an increase in the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI; the number of breath pauses or respiratory events per hour) of 32%. (23)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of OSA and the requirement for treatment are determined by the results of polysomnography (PSG) or home sleep apnea test (HSAT). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine established the most recent OSA diagnostic standards in 2014. (Table 2) (24)

| Polysomnogram or home sleep apnea test reveals |

| • ≥ 15 predominantly obstructive respiratory events per hour of sleep OR |

| • ≥ 5 predominantly obstructive respiratory events per hour of sleep and at least 1 of the following: |

| – Daytime sleepiness, nonrestorative sleep, fatigue, or insomnia |

| – Waking with breath-holding, gasping, or choking |

| – Observed loud snoring, breathing interruption, or both |

| – Hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, ischemic heart disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, or diabetes type 2 |

Table 2: obstructive sleep apnea diagnostic criteria (24)

The gold standard of OSA evaluation is polysomnography (PSG). (1) The more recent home sleep apnea test (HSAT), while convenient for some patients as a confirmatory test, may understate the severity of breathing disorders that are related to sleep. (25)

Respiratory events captured on a PSG or HSAT

The occurrence of obstructive respiratory events during sleep, such as apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory event-related arousals, is the basis for the OSA diagnostic criteria. (1)

Apneas. A respiratory event known as apnea causes a complete lack of airflow, as indicated by a thermal sensor reduction of more than 90% for 10 or more seconds. Obstructive, central, or mixed apneas are possible (Figure 1). When the airway is blocked and breathing effort is felt in the chest and abdomen, obstructive apneas happen (Figure 2). There is no airflow and no respiratory effort in central apnea, which means the brain is not telling the body to breathe. Lack of airflow with and without respiratory effort is brought on by mixed apneas. (1)

Figure 1: Apneas can be obstructive, mixed, or central (1)

Figure 2: Polysomnogram excerpts with normal sleep, obstructive apnea, obstructive hypopnea, and respiratory event-related arousal waveform findings. (1)

Severity

The severity of OSA should be included in the diagnosis (mild, moderate, or severe), as it may influence whether or not the patient receives treatment. AHI, respiratory disturbance index, or respiratory event index are used to quantify severity (Table 3). (26) A value of 5 to 14.9 for any of the 3 indices is regarded as mild, 15 to 29.9 as moderate, and 30 or higher as severe.

| Index | Calculation |

| Apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) | (Apneas + Hypopneas) / Total Sleep Time, hours |

| Respiratory disturbance index | (AHI + Respiratory event-related arousal) / Total Sleep Time, hours |

| Respiratory event index | (Apneas + Hypopneas) / Total monitoring time, hours |

Table 3: Respiratory event index is typically used for home sleep apnea testing as it is based on monitoring time as distinct from actual sleep time. (26)

OSA in pediatric patients

The ICSD-3 recommends two methods for determining whether a child has OSA: one is clinically based on the presence of one or more symptoms (excessive daytime sleepiness, behavioral changes, snoring, shortness, paradox, or blocked breath during sleep). (24)

One or more obstructive apneas, mixed apneas, or hypopneas for sleep time, or 25% of TST with hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 50 mmHg) in association with one or more of the following parameters: snoring, flattening of the flow curve, or thoracoabdominal paradox movement, constitute the second criteria. (24)

DSM 5 Diagnostic Criteria (27)

- Either (1) or (2):

- Evidence by polysomnography of at least five obstructive apneas or hypopneas per hour of sleep and either of the following sleep symptoms:

- Nocturnal breathing disturbances: snoring, snorting/gasping, or breathing pauses during sleep.

- Daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or unrefreshing sleep despite sufficient opportunities to sleep that is not better explained by another mental disorder (including a sleep disorder) and is not attributable to another medical condition.

- Evidence by polysomnography of 15 or more obstructive apneas and/or hypopneas per hour of sleep regardless of accompanying symptoms.

Specify current severity:

Mild: Apnea hypopnea index is less than 15.

Moderate: Apnea hypopnea Index is 15-30.

Severe: Apnea hypopnea index is greater than 30.

Physical examination

Physical exam findings that might point to OSA include the following: (6)

- greater than 17 inches for men and 16 inches for women in the neck circumference

- greater than 30 BMI

- Tongue position Friedman class 3 or higher (Figure 3)

- Features of the mouth (macroglossia, enlarged or present tonsils)

- nasal deviations (turbinate hypertrophy, deviated septum).

Figure 3: Friedman palate positions (classes 1, 2, 3, and 4). (6)

Management & Treatment

The goal of treating OSA is to lessen symptoms, enhance the quality of life, lessen the burden of co-morbidities, and reduce mortality. As a result, the treatment plan for a specific patient should be customized based on the severity of OSA and any associated co-morbidities. (7)

Treatments for OSA include changing one’s behavior, losing weight, taking medication, applying continuous positive airway pressure, using oral appliances (such as tongue-retaining devices, orthodontic appliances, or mandibular advancing appliances), and having surgery (e.g., tracheostomy, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty, surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion, maxillomandibular advancement, and hypoglossal nerve stimulation). (31)

The potential causes of OSA are addressed by behavioral therapies. All OSA patients should refrain from using alcohol and sedatives. By reducing apneic episodes and snoring, weight loss has a positive effect on airway patency for some patients. Avoiding the supine position while you sleep may help some patients experience fewer sleep apnea episodes. The effectiveness of suggested pharmacotherapeutic treatments for OSA has not been established, and the role of pharmacotherapy in treating OSA is still unknown. (31)

Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), in which the upper airway is splinted open to improve patency during sleep, is the first-line treatment for OSA. When used properly and regularly, CPAP effectively reduces sleepiness symptoms and enhances the quality-of-life indicators in people with moderate to severe OSA. (32) With a success rate of about 75%, CPAP is regarded as the best treatment option for moderate-to-severe OSA. Sadly, reported nonadherence rates (where adherence is defined as using a CPAP for at least 4 hours each night) range from 46% to 83%. (33) However, patients who reject or are unable to tolerate CPAP must have other treatment options.

Prevention

Since obesity is the single biggest risk factor for developing OSA, preventing or reducing overweight and obesity is the most efficient way to lower OSA rates in a population. OSA appears to be significantly reduced following significant weight loss in several RCTs, and this appears to hold true for both dietary and surgical approaches. (28–30) There is, however, a dearth of evidence demonstrating that weight loss techniques can significantly lower OSA occurrence over time.

Conclusion

Despite our growing understanding of OSA, there are still unanswered questions and issues with suggested OSA treatments. By assisting in the provision of the highest caliber of healthcare to OSA patients, multidisciplinary teams made up of dentists, orthodontists, and oral-maxillofacial surgeons can lay the groundwork for addressing these issues. Effective OSA management depends on team members staying in touch and following up.