Topic: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Author: Ala’ Moh’d Al Barbarawi

Scientific Editor: Ahda Jbarah

Linguistic Editor: Aroob Awwad Awwad.

(31)

(31)

Understanding PTSD

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has adopted multiple names throughout history, including ‘shell shock’ during the first world war, and ‘combat fatigue’ the WWII. However, PTSD isn’t only present in soldiers who fought during war. It is a psychiatric disorder that can occur in people who have been through or witnessed a traumatic event which can be a natural disaster, a life-threatening accident, a terrorist act, war, combat, or rape. It can also happen to individuals who have been threatened with death, sexual violence, or serious injury. (1)

Epidemiology

PTSD is not specific to a certain age group, nationality, culture, or ethnicity. It affects approximately 3.5% of U.S. adults every year, and it is estimated that around 1 in 11 persons will be diagnosed with PTSD in their lifetime. That being said, PTSD was found to occur twice more likely in women as well as three ethnic groups, (U.S. Latinos, African Americans, and American Indians), who were shown to have higher rates of PTSD than non-Latino whites. (1)

Assaultive violence holds the highest potential for developing PTSD. In males, the preeminent factor for acquiring PTSD is combat-related violence. However, in females, sexual violence is the strongest predictor. Women and younger people are more vulnerable to this disorder. Nevertheless, it is increasingly being recognized among the elderly. (2)

Etiology

PTSD is a syndrome that results from exposure to threatened or serious injury or sexual assault. Its signs and symptoms appear to arise from complex interactions of psychological and neurobiological factors (e.g. certain genes can increase the risk).

In PTSD patients, alterations have been found to occur in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, anterior cingulate, corpus callosum, as well as altered functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA).

Risk and Prognostic Factors

Most people can quickly recover from certain trauma, meaning that they do not experience the dangerous psychological and physiological consequences of severe stress. However, those who do suffer from PTSD show some levels of vulnerability to these consequences. There are specific factors that promote resilience or vulnerability. (2)

According to DSM-5, risk and protective factors are generally divided into pre-traumatic, peritraumatic, and posttraumatic factors.

Pre-traumatic factors:

- Temperamental factors: consist of childhood emotional problems up to the age of 6 years (e.g., prior traumatic exposure, externalizing, or anxiety problems) and prior mental disorders (e.g., panic disorder, depressive disorder, PTSD, or obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD]).

- Environmental factors: include exposure to prior trauma (especially during childhood), lower socioeconomic status, childhood adversity (e.g. economic deprivation, family dysfunction, parental separation or death), cultural characteristics (e.g., fatalistic [one who believes that bad events cannot be avoided] or self-blaming coping strategies), minority ethnic status, lower intelligence, and a family history of psychiatric disorders. Social support before traumatic event exposure is protective.

- Genetic and physiological factors: include female gender and younger age at the time of trauma exposure (for adults). Specific genotypes can either protect against or increase the risk of PTSD after exposure to traumatic events.

- Genetic Risk Factors

- Polymorphisms in the Serotonin transporter gene affect the outcome; the long allele (l) in the SLC6A4 gene may have a protective effect while the short allele (s) may contribute to developing stress-related psychopathology(2,3).

- Higher risk is seen in different single nucleotide polymorphisms of the gene encoding a chaperone protein that influences the transcriptional effects of the glucocorticoid receptor (FKBP5). This higher risk is observed in children exposed to physical and sexual abuse. (4)

- Single nucleotide polymorphism in the BDNF gene influences the process of fear extinction; a physiologic mechanism relevant to PTSD pathophysiology (5).

- Different single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene encoding the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-1 (CRHR1) appear to lower the risk of developing stress-related disorders among women with a history of childhood abuse(6). Similarly, the long-form variant of the neuropeptide Y (NPY) gene has been linked with a decreased risk of developing PTSD(7).

- Gender: Women may be at higher risk due to variations in hormonal levels. The levels of testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) are positively correlated with resilient behavior (8,9,10) while the fluctuating levels of ovarian hormones (estrogen and progesterone) are correlated positively with anxious responses to stress (vulnerability)(11). However, high levels of oxytocin may decrease the risk of stress-related psychopathology(12).

- Lower performance on neuropsychological tasks assessing fluid intelligence (which is the ability to solve novel problems independently of previously acquired knowledge) was more vulnerable(13,14).

- Genetic Risk Factors

Peritraumatic factors

- Environmental factors: these include trauma severity (the greater the magnitude of the trauma, the greater the possibility of acquiring PTSD), perceived life threat, personal injury, and interpersonal violence (particularly if the trauma is caused by a caregiver or witnessing a threat to a caregiver in children). Also, adults with a history of childhood abuse are more likely to develop PTSD after adulthood trauma(2).

- Being in the military(2): being a perpetrator, witnessing atrocities, or killing the enemy.

- Dissociation taking place during the trauma and persisting

Posttraumatic factors

- Temperamental factors: compromised of negative appraisal, inappropriate coping mechanisms, and development of acute stress disorder.

- Environmental factors: include subsequent exposure to repeated upsetting reminders, subsequent adverse life events, and financial or other trauma-related losses. Family stability and support for children is a protective factor.

Differential Diagnosis(15)

PTSD must be differentiated from other post-traumatic disorders and conditions, adjustment disorders, acute stress disorder, anxiety disorders, OCD, major depressive disorder, personality disorders, dissociative disorders, conversion disorder (functional neurological symptom disorder), psychotic disorders, and traumatic brain injury.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria(15)

For adults, adolescents, and children older than 6 years:

- being exposed to death (whether real or threatened), severe injury, or sexual abuse through one or more of the following methods:

- Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s) (e.g., car accident, natural disaster, war).

- Being present, in person, as the event(s) occurred to others.

- Knowing that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend. If there was actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the event(s) must be violent or accidental.

- Repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) (e.g., first responders collecting human remains, police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse, and medical personnel dealing with terminally ill patients). This criterion does not apply to exposure through electronic media, TV, movies, shows, or pictures unless this exposure is related to work.

- One or more of the following intrusion symptoms associated with the trauma, starting after the event(s) occurred:

- Recurrent, involuntary, intrusive distressing memories of the event(s). In children older than 6 years, themes or aspects of the traumatic event (s) may be expressed through repetitive play.

- Repeated nightmares whose content and/or effect are related to the traumatic event(s). In children, there may be frightening dreams without recognizing the content.

- Flashbacks where the person feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring (these may occur continuously, their most extreme expression is the complete loss of awareness of present surroundings). In children, trauma-specific reenactment may occur when the child is playing.

- Intense or prolonged psychological distress when exposed to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s), (e.g., the individual may hear a certain sound related to the event, which can trigger psychological distress).

- Consistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning after the traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidenced by one or both of the following:

- Avoiding or trying to avoid disturbing thoughts, memories, or feelings regarding the traumatic event(s).

- Avoiding or trying to avoid external reminders (people, places, conversations, activities, situations, objects) that trigger the disturbing memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the traumatic event(s).

- Negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s), which begin or worsen after the traumatic event(s) occur, as evidenced by two or more of the following:

- Inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic event(s), due to dissociative amnesia and not other factors such as head injury, alcohol, or drugs.

- Persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs or expectations about oneself (e.g. “I am a bad person”), others (e.g., “I can’t trust anyone”), or the world (e.g., “The world is dangerous”).

- Constant cognitive distortion regarding causes or consequences of the traumatic event(s) leads to the individual blaming themselves or others.

- Persistently negative emotions (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame).

- Markedly decreased interest or desire to participate in significant activities.

- Feeling detached or isolated from other people.

- Continuous inability to experience positive emotions (e.g., happiness, satisfaction, love, etc.,).

- Marked alteration in arousal and reactivity linked to the traumatic event(s), beginning or worsening after the event(s) occurred, as evidenced by two or more of the following:

- Irritability and angry outbursts (without or with some provocation) manifested as verbal or physical aggression towards people or objects.

- Reckless or self-destructive behavior (e.g., drinking and driving, carrying concealed weapons).

- Hypervigilance (a state of increased alertness).

- Exaggerated startle response.

- Concentration problems.

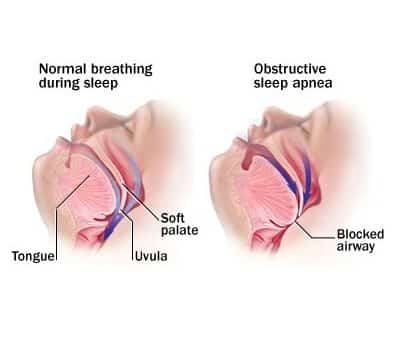

- Disturbances in sleep (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep or restless sleep).

- The disturbance, evidenced by criteria B to E above, lasts more than one month.

- The disturbance leads to clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The disturbance is not caused by the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., medication, alcohol) or another medical condition.

After confirming the diagnosis of PTSD, specify whether:

- The patient has dissociative symptoms: the individual will meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD in addition to experiencing persistent or recurrent symptoms of either of the following in response to the stressor:

- Depersonalization: the persistent or recurrent feeling of being detached from an individual’s mental processes or body as if they were an outside observer (e.g., feeling a sense of unreality as if one were in a dream or out of their body).

- Derealization: persistent or recurrent experiences of unreal surroundings (e.g., the world around the individual is experienced as unreal, dreamlike, distant, or distorted; people or objects may seem unreal). Note: To specify this subtype, these symptoms must not be caused by or associated with physiological effects of substance abuse (e.g., behavior during alcohol intoxication) or another medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures).

- With delayed expression: specified if the full diagnostic criteria are not met until at least 6 months after the traumatic event (although the onset and expression of some symptoms may be immediate).

PTSD in Children Six Years and Younger

To diagnose a child 6 years or younger the following criteria must apply:

- Being exposed to death (whether real or threatened), severe injury, or sexual abuse through one or more of the following methods:

- Experiencing the traumatic event(s) directly.

- Witnessing, in person, the traumatic event(s) as it occurred to others, especially primary caregivers (does not include events that are witnessed only in electronic media, television, movies, or pictures).

- Learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a parent or caregiver.

- Having one or more of the following intrusion symptoms related to, and beginning after, the traumatic event(s):

- Repeated, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s).

- Recurrent distressing dreams related to the traumatic event(s). However, it may not be possible to declare or decide that the frightening content is related to the traumatic event.

- Dissociative reactions (e.g., flashbacks) in which the child feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were taking place again.

- Exposure to internal and external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s) causes intense or prolonged psychological distress.

- Reminders of the traumatic event(s) result in marked physiological reactions.

- One or more of the following symptoms must be present, beginning or worsening after the event: either persistent avoidance of the stimuli or negative cognitive and mood changes associated with the traumatic event(s), the earlier manifests as:

1. Avoiding or efforts to avoid activities, places, or physical reminders of the traumatic event(s).

2. Avoiding or efforts to avoid people, conversations, or interpersonal situations

that arouse recollections of the trauma.

While the latter can manifest as:

1. Significantly increased frequency of negative emotions (e.g., fear, guilt, shame,

sadness, confusion).

2. Diminished interest or participation in activities, including constriction of play.

3. Socially withdrawn behavior.

4. Persistently reduced expression of positive emotions - Changes in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event(s) as evidenced by two or more of the following, beginning or worsening after the traumatic event(s) occurred:

- Angry outbursts and irritability (with little or no provocation), usually expressed as verbal or physical aggression toward people or objects and extreme temper tantrums.

- Hypervigilance (a state of increased alertness).

- Exaggerated startle response.

- Concentration problems.

- Disturbance in sleep (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep or restless sleep).

- The disturbance lasts more than 1 month.

- The disturbance causes clinically significant impairment in school behavior or social relationships.

- The disturbance is not due to nor associated with the physiological effects of certain substances (e.g., medication or alcohol) or another medical condition.

Once diagnosed, specify whether PTSD is with:

- Dissociative symptoms: The child’s symptoms meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. In addition, the child experiences persistent or recurrent symptoms of depersonalization or d Also, to use this subtype, the dissociative symptoms must not be caused by or associated with the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.

- Delayed expression: when the diagnostic criteria are not fully met until 6 months or more after the traumatic event.

Treatment

Treatment for PTSD is divided into two categories: psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

- Psychotherapy

The two most successful psychotherapy approaches are controlled exposure to aversive memories and cognitive processing(2). Other alternatives include are mentioned in Table 1 (16-22):

| Table 1: Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | |

| Exposure-Based | |

| Systematic Desensitization | Education* about disorder and treatment, involves imaginal exposure to aversive memories paired with relaxation to inhibit the feared stimuli. |

| Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) | Combines traumatic image exposure with the simultaneous performance of eye saccadic movements (usually lateral eye movements) |

| Stress Inoculation | Education*and training involving teaching coping skills to manage stress and anxiety associated with the traumatic event, training in deep muscle relaxation, exposure to aversive memories, role-playing, breathing exercises, assertiveness skills, and thought-stopping. |

| Prolonged Exposure | Education*, exposure to traumatic memories, confrontation of feelings/thoughts, cognitive restructuring |

| Virtual Reality Exposure | Exposure to computerized, vividly recreated environments of the trauma (e.g., war, accidents, etc.,) |

| Cognitive-Based | |

| Trauma-Focused Psychodynamic Therapy | Includes education*, free association, dream interpretation, and cognitive restructuring. |

| Cognitive Processing Therapy | Education* (with limited exposure to traumatic memories) along with Socratic questioning, and identification of maladaptive cognition and automatic thoughts (the patient becomes aware of the relationship between thoughts and emotions). |

| Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) | Individuals open up to unpleasant feelings and learn not to overreact and to face situations where they are invoked. |

| Other | |

| Biofeedback | Voluntary regulation of physiologic responses (e.g., muscle activity, heart rate). A mind-body technique involving visual or auditory feedback to gain control over involuntary bodily functions such as blood flow, blood pressure, and heart rate (23). |

| Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy | Involves meditation, awareness, breath-focused imagery, silent repetition of words, and letting go of intrusive thoughts. |

*Note: Education involves psychoeducation regarding PTSD, thoughts, and emotions

2. Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacologic treatment of PTSD is usually indicated either to prevent its onset after trauma exposure or to reduce the severity of PTSD symptoms once the condition is established. A recent meta-analysis of preventive interventions indicated that hydrocortisone may be used to prevent PTSD onset when given acutely after trauma(24). On the other hand, no preventive effect was seen when propranolol, benzodiazepines, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were given(24). However, the clinical trials conducted in the analysis were small and had multiple methodologic flaws(24).

Another recent meta-analysis of pharmacologic interventions to reduce the severity of PTSD symptoms suggests that placebo is less effective than active pharmacologic agents. However, the side effects observed in the concisely controlled trials were smaller than those observed in controlled trials of psychotherapeutic options. Furthermore, little evidence exists proving that the combination of medications and psychotherapy has a synergistic effect, and no effectiveness studies comparing pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy exist. (25)

It is unlikely that one particular medication is equally efficacious in treating all PTSD symptom clusters (e.g., intrusive symptoms, avoidance, dysphoric experiences) since symptoms are heterogeneous and have different pathophysiologic mechanisms. Moreover, the longitudinal course of PTSD may influence efficacy. In other words, a pharmacologic agent might be more effective in the early stages of PTSD while another is better given in the more refractory, chronic period. (2)

A summary of the medications that have shown some efficacy in treating PTSD is shown in Table 2 below (2):

| Table 2: Medications That Have Shown Efficacy in Treating PTSD | ||

| Class | Drug | Total Daily Dosage |

| Antidepressants | ||

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | Fluoxetine

Sertraline Paroxetine Citalopram |

20-60 mg/d

50-200 mg/d 20-30 mg/d 20-40 mg/d |

| Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) | Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine- extended-release Duloxetine |

75-300 mg/d

75-225 mg/d

40-60 mg/d |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) | Amitriptyline

Imipramine |

50-300 mg/d

50-300 mg/d |

| Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors | Phenelzine | 15-90 mg/d |

| Other | Mirtazapine | 7.5-45 mg/d |

| Sympatholytic | ||

| Beta-blockers | Propranolol | 40-160 mg/d |

| Alpha-2 Receptor agonists | Clonidine

Guanfacine |

0.2-0.6 mg/d

0.5-3 mg/d |

| Alpha-1 Receptor antagonists | Prazosin | 2-10 mg/d |

| Mood Stabilizers | ||

|

Divalproex sodium or valproic acid Lithium Carbamazepine Topiramate |

500-2000 mg/d

600-1500 mg/d 400-1000 mg/d 50-200 mg/d |

|

| Antipsychotics | ||

| Risperidone

Olanzapine Quetiapine Aripiprazole |

0.5-6 mg/d

5-20 mg/d 25-300 mg/d 5-15 mg/d |

|

| Anxiolytics | ||

| Benzodiazepines | Alprazolam

Clonazepam |

0.25-4 mg/d

0.5-4 mg/d |

| 5-HT1A receptor agonists | Buspirone | 15-60 mg/d |

| Others | ||

| N-methyl-D-aspartate | D-Cycloserine | 8-12 mg/d |

| (NMDA) antagonists | Ketamine | 0.5 mg/kg/d IV |

When initiating pharmacotherapy for PTSD treatment, SSRIs are the drugs of choice as they have the best safety profile compared to other medications (2). When compared to placebo, previous studies have shown that sertraline(26), paroxetine(27), and fluoxetine(28) are significantly more efficacious in reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms. However, it should be noted that this efficacy is due to differences in gender, type of traumatic event, refractoriness of PTSD, and symptom clusters(2). For instance, military populations tend to be less responsive to treatment with SSRIs(2). A randomized double-blind trial performed in 10 US Department of Veteran Affairs medical centers shows that sertraline is not more effective than a placebo to treat combat-related PTSD(29). SNRIs like venlafaxine might be more effective in PTSD treatment(2).

Antiadrenergic agents may influence specific PTSD-symptom dimensions. For example, the alpha1 receptor antagonist prazosin shows efficacy in reducing the frequency and severity of intrusive symptoms (e.g., nightmares)(30). Mood stabilizers such as lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine are ineffective in treating PTSD, but they can be helpful for those patients with coexistent bipolar disorder(2). Similarly, comorbidities including impulsivity and substance misuse in PTSD patients may be decreased with the use of topiramate. The addictive potential of benzodiazepines limits their use for the treatment of PTSD. Moreover, it may lead to aggravating avoidance and depressive symptoms(2). Lastly, although the use of antipsychotics is discouraged, atypical neuroleptics might constitute a last-resort solution to control disturbing psychotic symptoms(2).

Prognosis

Certain genetic factors may be protective, leading to a better prognosis when compared to susceptibility genes. The severity of the trauma also plays an important role in prognosis. Does PTSD regress with time or does it worsen with time? This mainly depends on how soon symptoms develop, their severity, early diagnosis, and treatment. (1)

References

- What Is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder? 2020. p. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/.

- Jorge RE. Posttraumatic stress disorder. Contin Lifelong Learn Neurol. 2015;21(3):789–805.

- Murrough JW, Charney DS. The serotonin transporter and emotionality: Risk, resilience, and new therapeutic opportunities. Biol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2011;69(6):510–2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.019

- Binder EB, Bradley RG, Liu W, Epstein MP, Deveau TC, Mercer KB, et al. Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA. 2008 Mar;299(11):1291–305.

- Soliman F, Glatt CE, Bath KG, Levita L, Jones RM, Pattwell SS, et al. A genetic variant BDNF polymorphism alters extinction learning in both mouse and human. Science. 2010 Feb;327(5967):863–6.

- Polanczyk G, Caspi A, Williams B, Price TS, Danese A, Sugden K, et al. Protective effect of CRHR1 gene variants on the development of adult depression following childhood maltreatment: replication and extension. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;66(9):978–85.

- Zhou Z, Zhu G, Hariri AR, Enoch M-A, Scott D, Sinha R, et al. Genetic variation in human NPY expression affects stress response and emotion. Nature. 2008 Apr;452(7190):997–1001.

- Ahmet Koyuncu MD1, Ezgi İnce MD2, Erhan Ertekin MD2 RTM. Comorbidity in social anxiety disorder: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6448478/

- Olff M, de Vries G-J, Güzelcan Y, Assies J, Gersons BPR. Changes in cortisol and DHEA plasma levels after psychotherapy for PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007 Jul;32(6):619–26.

- Yehuda R, Brand SR, Golier JA, Yang R-K. Clinical correlates of DHEA associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006 Sep;114(3):187–93.

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL, Kramer TL. Vulnerability-stress factors in development of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992 Jul;180(7):424–30.

- Koch SBJ, van Zuiden M, Nawijn L, Frijling JL, Veltman DJ, Olff M. Intranasal oxytocin as strategy for medication-enhanced psychotherapy of PTSD: salience processing and fear inhibition processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014 Feb;40:242–56.

- Breslau N, Chen Q, Luo Z. The role of intelligence in posttraumatic stress disorder: does it vary by trauma severity? PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65391.

- Macklin ML, Metzger LJ, Litz BT, McNally RJ, Lasko NB, Orr SP, et al. Lower precombat intelligence is a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998 Apr;66(2):323–6.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) [Internet]. Available from: https://books.google.jo/books/about/Diagnostic_and_Statistical_Manual_of_Men.html?id=-JivBAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- WOLPE J. The systematic desensitization treatment of neuroses. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1961 Mar;132:189–203.

- Shapiro F. Eye movement desensitization: a new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1989 Sep;20(3):211–7.

- McLean CP, Foa EB. Prolonged exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: a review of evidence and dissemination. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011 Aug;11(8):1151–63.

- Powles WE. Beck, Aaron T. Depression: Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972. Pp. 370. $4.45. Am J Clin Hypn [Internet]. 1974 Apr 1;16(4):281–2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1974.10403697

- Powers MB, Zum Vorde Sive Vording MB, Emmelkamp PMG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: a meta-analytic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(2):73–80.

- Batty MJ, Bonnington S, Tang B-K, Hawken MB, Gruzelier JH. Relaxation strategies and enhancement of hypnotic susceptibility: EEG neurofeedback, progressive muscle relaxation and self-hypnosis. Brain Res Bull. 2006 Dec;71(1–3):83–90.

- Zucker TL, Samuelson KW, Muench F, Greenberg MA, Gevirtz RN. The effects of respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback on heart rate variability and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2009 Jun;34(2):135–43.

- Cherry K. What Is Biofeedback and How Does It Work? [Internet]. Available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-biofeedback-2794875#:~:text=Biofeedback is a mind-body,blood pressure%2C and heart rate.

- Amos T, Stein DJ, Ipser JC. Pharmacological interventions for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2014 Jul;(7):CD006239.

- Stein DJ, Ipser JC, Seedat S. Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2006 Jan;2006(1):CD002795.

- Bravo-Mehmedbasic A, Dzubur Kulenovic A, Kucukalic A. P.4.b.012 Efficacy and safety of sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:S593–4.

- Marshall RD, Beebe KL, Oldham M, Zaninelli R. Efficacy and safety of paroxetine treatment for chronic PTSD: a fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001 Dec;158(12):1982–8.

- Martenyi F, Brown EB, Zhang H, Prakash A, Koke SC. Fluoxetine versus placebo in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 Mar;63(3):199–206.

- Friedman MJ, Marmar CR, Baker DG, Sikes CR, Farfel GM. Randomized, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder in a Department of Veterans Affairs setting. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007 May;68(5):711–20.

- Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, Hoff DJ, Hart K, Holmes H, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Sep;170(9):1003–10.

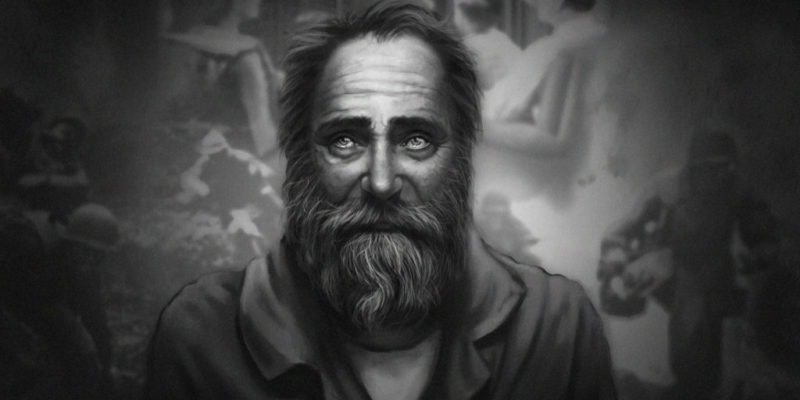

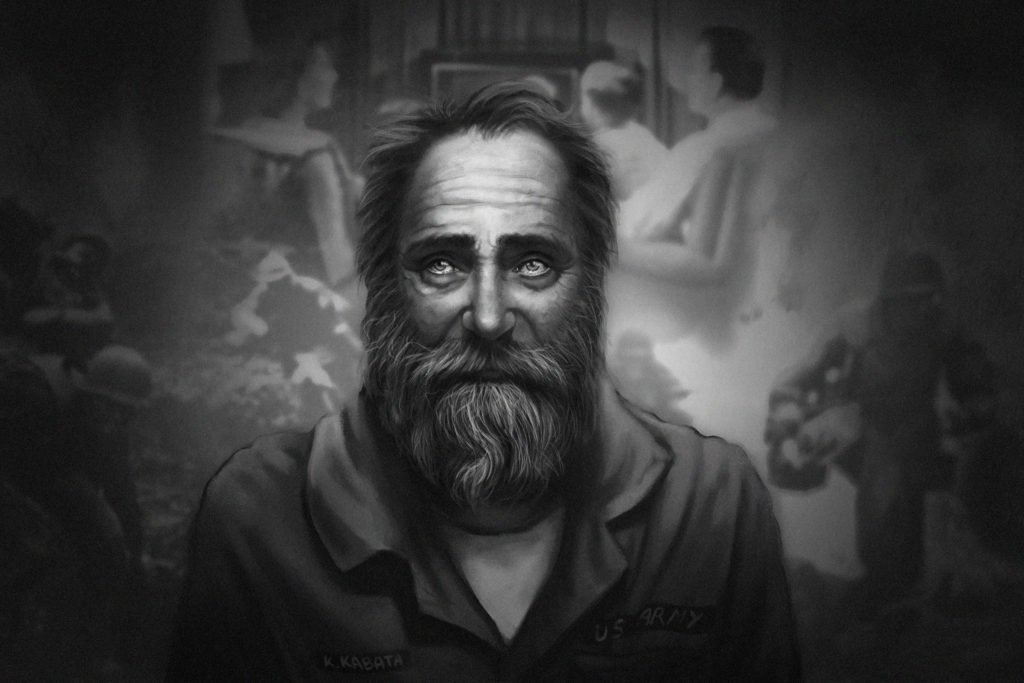

- KabatArt. Mental Illness PTSD [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 3]. Available from: https://images-wixmp-ed30a86b8c4ca887773594c2.wixmp.com/f/9e9c85cf-c32d-4bc2-93ba-0c9cce038988/dd0mdlp-e875ac07-d542-42bd-921a-9adad20c5e72.jpg/v1/fill/w_1095,h_730,q_70,strp/mental_illness___ptsd_by_kabatart_dd0mdlp-pre.jpg?token=eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGci