Article topic: Cluster Headache

Author: Tala Mohammad

Editors: Nicola AL-Madani, Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: Unilateral, trigeminal, episodic, chronic, headache, sumatriptan.

Overview

Cluster headache is a primary headache disorder, part of the family of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TCAs), characterized by excruciating unilateral pain, often involving the supraorbital, retro-orbital, or temporal regions1. All TACs share the common feature of unilateral pain, accompanied by prominent cranial parasympathetic autonomic features, which are usually ipsilateral to the headache2. Attacks of cluster headache may range between 15-180 minutes, occurring anywhere between once every other day to up to eight times per day2. Cluster headache has also been referred to as “suicide headache” due to the fact that some patients have taken their lives during an attack3. Moreover, cluster headache has also been portrayed as worse than childbirth 4 which further outlines the severity of attacks.

Epidemiology

Given the low prevalence of cluster headache when compared to migraine, it is challenging to assess accurately the abundance of cluster headache in the community 5 . Based on surveys conducted in the USA and Europe, cluster headache constitutes up to 0.1% of the population, with no evidence on whether the prevalence differs according to the region6. Cluster headache has been shown to have a significant male predominance, with an approximate male-to-female ratio of 2.5:15. The mean age of onset has been shown to be between 20 and 40 years7. Epidemiologic studies regarding cluster headache have been mainly performed on Caucasians5. One study concluded that up to 80% of patients partaking in the study, who suffer from cluster headache, were smokers, suggesting strong evidence to the correlation between both factors.8

Pathogenesis and etiology

Many structures within both the peripheral and central nervous systems are involved in the pathophysiology of cluster headache. Cluster headache is generally neurovascular in nature, with effects driven by the effects of the trigeminal-autonomic reflex activation5. The trigeminal-autonomic reflex is a pathway connecting the trigeminal nerve and facial nerve parasympathetic innervation, located in the brainstem5. Central activation can take place in the brainstem through the superior salivatory nucleus, which is a part of the facial nerve9. The superior salivatory nucleus is the origin of cranial parasympathetic autonomic vasodilator fibers, and its effects are mediated by several substances, including calcitonin gene-related peptide and nitric oxide9. This central activation is significant in the pathophysiology of cluster headache, mainly through the involvement of the posterior hypothalamus9, Figure (1). In primary headache, the activation of the trigeminal-autonomic reflex leads to typical symptoms which include; rhinorrhea, miosis, ptosis, conjunctival injection, and facial sweating4. These autonomic symptoms are very prominent in cluster headache, mainly ipsilateral to the source of the headache. Conventionally, attacks due to cluster headache can be summarized as a combination of trigeminal activation and reactive parasympathetic increase6.

Fig (1) Overview of the structures involved in the pathophysiology of cluster headache 9

Clinical presentation and complications

The clinical manifestations of cluster headache can be summarized into four keywords; side-locked, excruciating, agitating, and regularly recurring9 . Cluster headache can be presented either episodically or chronically, depending on the duration between the attacks. The most common presentation among patients is the episodic form, comprising up to 90% of all cases6 . Episodic cluster headache typically refers to attacks that occur in periods ranging from seven days up to a year, with attack-free periods lasting at least three months2. However, chronic cluster headache presents with attacks occurring for one year either without pain-free periods, or pain-free periods of less than three months2 . During the attacks, patients are typically agitated and restless1, a key factor in distinguishing cluster headache from migraine.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of cluster headache relies heavily on the accurate history of the patient1. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition, the diagnostic criteria for cluster headache is as follows2:

- Five or more attacks fulfilling criteria B-D

- Severe or extremely severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital, and/or temporal pain, lasting anywhere between 15 minutes and three hours (when untreated)

- Either or both of the following,

- At least one of the following symptoms, ipsilateral to the headache

- Conjunctival injection, may be accompanied by lacrimation

- Nasal congestion with or without rhinorrhoea

- Eyelid oedema

- Forehead and facial sweating

- Miosis and/or ptosis

- A sense of restlessness or agitation

- At least one of the following symptoms, ipsilateral to the headache

- Attack frequency between once every other day and eight times a day

- Not better accounted for by other ICHD-3 diagnoses

Patients often have a delayed diagnosis or are simply misdiagnosed. A possible underlying reason can be the limited knowledge on cluster headache throughout many countries10. This lack of knowledge may also lead the physician to seek an alternative diagnosis for the patient, which increases the risk of misdiagnosis.10

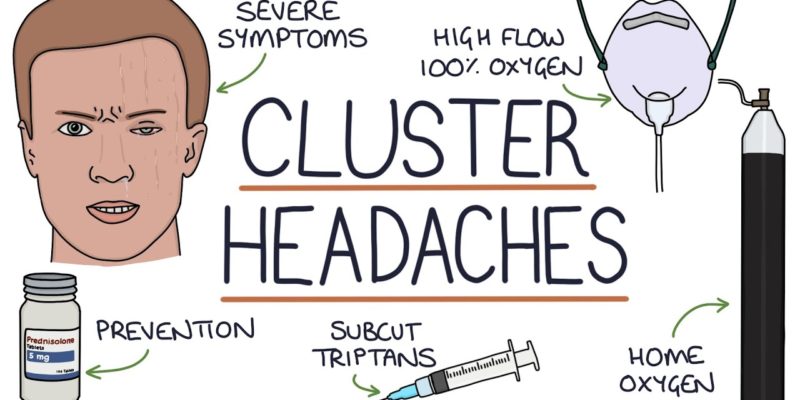

Treatment and Management

Management of cluster headache is divided into acute and preventative management, both of which are further subdivided into several treatments. Acute treatment for cluster headaches can be achieved by sumatriptan, zolmitriptan, high-flow oxygen, and non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation1. The most effective treatment for cluster headache by far is subcutaneous sumatriptan11. Verapamil is often used as the first-line preventive treatment for cluster headaches1. However, side effects may arise, including cardiac arrhythmias and bradycardia1. Another medication used in preventive treatment is lithium. Evidence on the efficacy of lithium in the treatment of cluster headache is limited1. A review of literature suggests that lithium is most efficacious when used in treating chronic cluster headache12. Oral treatment is not recommended due to the short duration of the attacks11. One therapy that has been proven effective is oxygen therapy although the underlying pathophysiology remains unclear11,13. Compared to medications such as sumatriptan and zolmitriptan, oxygen implicates few side effects and is especially useful in patients suffering from more than two attacks per day 1,13. Furthermore, studies have established the effectivity of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation when used in both acute and preventive treatments14. Not to mention, sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation elicits both acute and preventive responses, presenting as a reduction in the need for both acute and preventive treatments in a study population15. Serum levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) are elevated in cluster headache during cluster periods11. Thus, the administration of galcanezumab, a monoclonal antibody against CGRP, has been implicated in the treatment of episodic cluster headache by reducing the frequency of weekly attacks1,16.

Risk factors

Many papers have outlined several risk factors that may be implicated with cluster headache. A systemic review outlined the major risk factors involved in cluster headache, including family history, smoking, alcohol consumption, and even head trauma17. Not to mention, according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition, attacks are often triggered by alcohol, histamine, or nitroglycerin2. Tobacco smoking has been reported to be one of the leading risk factors in cluster headache, also playing a role in the transition between episodic and chronic forms.17 According to a systematic review, cluster headache has been exhibited as an inherited disorder in certain families, with a female predominance towards familial cluster headache18. Thus, there are certain genetic patterns that may be supplementary with cluster headache.

Prognosis

Prognosis has been shown difficult to predict5.A study carried out to analyze the patterns in cluster headache over 10 years has shown that approximately 20% of episodic cluster headache shows a shift towards either chronic or “combined” forms19. Factors that support such shift include a disease ongoing for more than 20 years, late-onset age, and male patients19. Based on personal experience, patients have reported the amelioration of their cases with age, characterized by longer remission periods and decreased frequency of attacks20. Long remission periods do not fully indicate recovery19.

Recent updates21

A recent retrospective study viewed the use of greater occipital nerve (GON) injection as a treatment. GON injection has been proven effective as a single injection in episodic cluster headache and chronic cluster headache, to a lesser extent. Moreover, similar results were seen with patients suffering from medically intractable chronic cluster headache (MICCH). The treatment used in the study was in the form of both single and repeated injections. As a summary, in the retrospective cohort, single GON injections were proven as an effective prophylactic treatment equally in episodic cluster headache, chronic cluster headache, and MICCH.

References...