Topic: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Author: Rama Qatarneh

Introduction

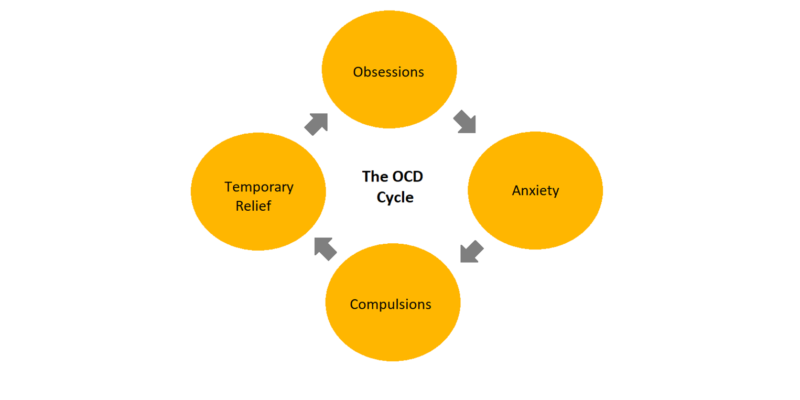

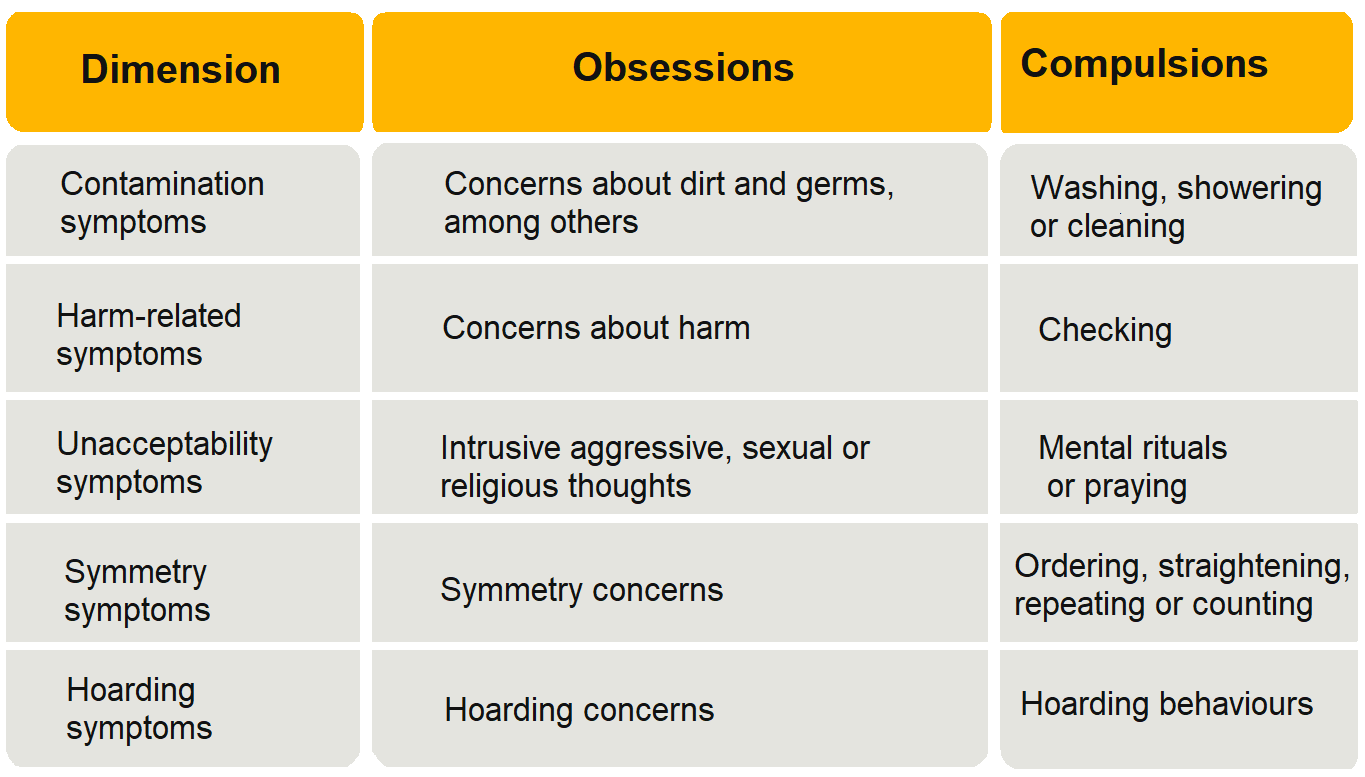

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common, usually chronic mental disorder denoted by two key features; intrusive obsessions, and repetitive behaviors or compulsions. Obsessions include thoughts, images, or impulses to carry out specific tasks that are often unsettling and anxiety-provoking, while compulsions involve performing repetitive motor acts which normally serve to temporarily offset the distress of obsessions (Fig.1) (1).

Previously, OCD was recognized as one of the anxiety disorders. However, starting with the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) it was added to a new section termed obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (OCRDs) (2). Even though major overlaps between OCD and the other OCRDs exist; including intersecting comorbidities and family history (3,4), there are also crucial differences in their biology, assessment, and management (5,6).

Fig.1|

Epidemiology

The lifetime prevalence of OCD roughly ranges between 1% to 3% in adults (7,8) and adolescents (9), yet it is substantially more frequently encountered in psychiatric and medical practices than these figures indicate due to its chronicity. The age of onset reported by OCD patients assumes a bimodal pattern, with symptoms often appearing in childhood/adolescence in males and early adulthood in females (10).

When taking into consideration the role of gender, past studies utilizing samples of children noted a greater proportion of males presenting with OCD (11–13), whereas samples of adults identified a greater proportion of females (14).

Clinical Presentation

OCD patients present with obsessions, compulsions, or in the majority of cases both. Obsessions are persistent, disturbing, undesired thoughts, images, or urges that go against the patient’s personal beliefs (ego-dystonic). They cause marked distress, consequently attempts are made to ignore, suppress, or neutralize them with other thoughts or acts. Recurring themes incorporate concerns about contamination, safety or harm, unwanted acts of aggression, inappropriate sexual or religious thoughts, and the necessity for symmetry or exactness. Whereas compulsions are repetitive habits or mental acts the person feels forced to execute, either as a reaction to an obsession (e.g., to stop a dreaded event from taking place) or according to set rules designed to prevent or lessen distress. The acts are evidently excessive or irrational and usually reduce anxiety, but are not pleasurable. Regularly encountered compulsions involve exaggerated cleaning, checking, counting, repeating routine activities, and hoarding (Fig.2). Overall, symptoms give rise to significant distress, are time-consuming (>1 h/d), or hinder function (1).

In 90% of cases, patients with lifetime OCD present with other comorbid disorders, most commonly including anxiety disorders, mood disorders, impulse-control disorders, substance use disorders, tic disorders, and other OCRDs (8).

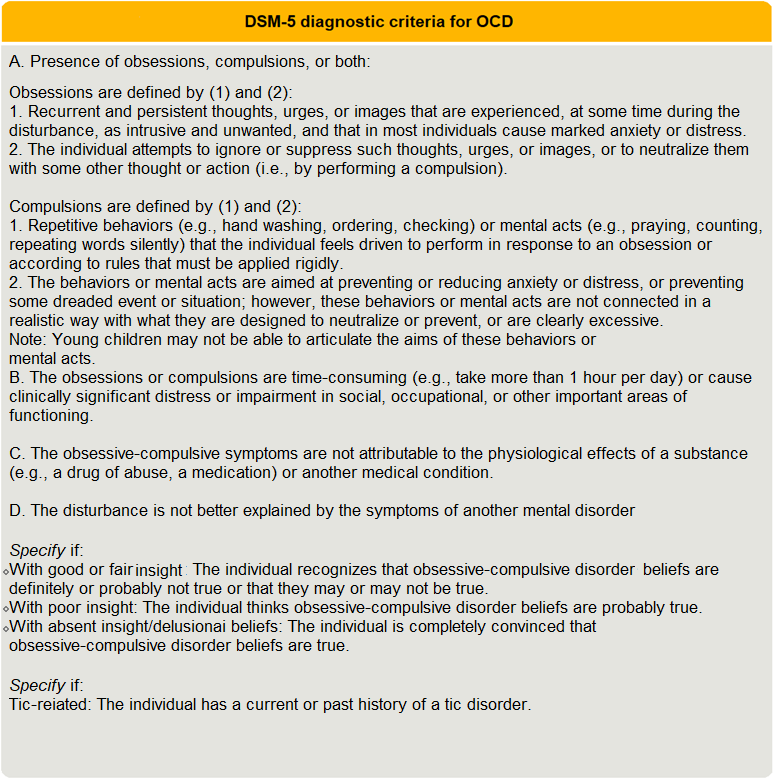

Throughout the course of illness, most patients have insight at some point, as they can acknowledge their symptoms to be senseless or excessive. Nevertheless, this is not the case for all patients and the DSM-5 criteria permits for a range of insight (Fig.3) (15).

Fig.2 | OCD symptom dimensions. (16)

Differential Diagnosis

OCD should be differentiated from several other psychiatric conditions (16,17):

- Anxiety and depressive disorders

Worries and thoughts involved in generalized anxiety disorder and depression are usually about real-life concerns and are more likely to be less irrational. Compulsions are also not usually encountered in these conditions.

- Autism spectrum disorders

It may be challenging to distinguish obsessions and compulsions from the restricted, repetitive, and inflexible activities and interests seen in autism spectrum disorders; still, OCD patients do not commonly present with the difficulties in social communication or reciprocal social interactions encountered in autism spectrum disorders.

- Other OCRDs

Even though repetitive thoughts and acts take place in a range of other OCRDs (as in hoarding disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, excoriation disorder, and trichotillomania), the main concerns and forms of repetitive behaviors in all these conditions are different from those in OCD.

- Psychotic disorders

Having insight may differentiate OCD from a psychotic illness, such as schizophrenia. Yet in patients with OCD and poor or absent insight, differentiation can be reached by noting the absence of additional features present in psychotic illnesses, such as hallucinations and formal thought disorder.

- Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

Patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder are inclined towards perfectionism and rigid control but they express their thoughts as appropriate rather than intrusive in the way that obsessions are experienced.

- Tic disorders

Tics are characterized by sudden, rapid, recurrent, non-rhythmic behaviors and are not driven by the urge to alleviate anxiety as a result of obsessive thoughts, rather, they are thought to be driven by somatic discomfort.

Risk Factors

Potential risk factors for developing OCD are (18):

- Age (late adolescence)

- Genetic Factors

- Race (non-white)

- Being unmarried

- Abusing drugs

- Presence of other mental conditions (mood and anxiety disorders)

Etiology

To this day, the precise etiology behind OCD is not fully understood. However, multiple plausible theories exist:

- Molecular mechanisms

Several key neurotransmitters are found to be implicated in OCD including serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate (19–21). When it comes to the involvement of serotonin, the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and clomipramine play an important part in the treatment of OCD, hence proving its role (19,20). As for dopamine, dopamine agonists and reuptake inhibitors may cause or aggravate OCD symptoms (22–24). In glutamate, evidence backing its role in OCD involves neurochemical studies, genetic studies, pharmacological experiments, and case reports with glutamate-altering drugs (25).

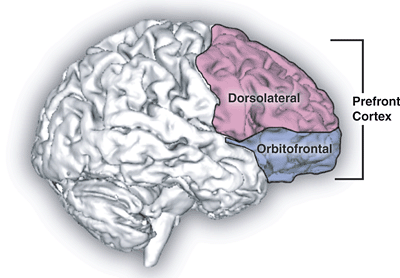

- Neurobiological

The use of structural and functional brain imaging modalities illustrated that some areas within the brain are involved in the pathophysiology of OCD. These are the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate gyrus, and caudate nucleus. Additionally, the superior temporal gyrus, parietal lobe, and hippocampus may also be affected (26,27).

Involvement of the basal ganglia has been reported as well. The basal ganglia are composed of the striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), globus pallidus, substantia nigra, nucleus accumbens, and subthalamic nucleus. They function in compound integrative motor and behavioral functions such as the execution of learned behaviors (28). Lesions within the basal ganglia were noted to induce acquired OCD (27,29).

Finally, OCD may be owing to a defect involving the cortico–striato–thalamo–cortical circuit. A crucial role for this network is maintaining self-control (30–32).

- Genetic

The risk of having OCD is raised by two folds in the presence of first-degree relatives, yet, if individuals among first-degree relatives have childhood-onset OCD, the risk is further increased by ten folds (2). Certain genes implicated in the development of OCD are:

- Serotonergic genes: include the 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter, 5HT2a serotonin receptor, 5HT1D beta receptor gene, and the serotonin 5HT2c receptor(33).

- Dopaminergic genes: some studies demonstrate replications in the dopamine receptor type 4 (DRD4) gene (33).

- Glutamatergic genes: such as the glutamate transporter gene, SLC1A1, and the gene encoding for ionotropic glutamate receptors, SAPAP3 (25).

- Other genes: additional genes that can be complicated with OCD are the SLITRK1, BDNF locus, gamma-aminobutyric acid type receptor 1 (GABBR1), OLIG2, and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein(33,34)

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Fig.3| DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; obsessive–compulsive disorder (2)

Management

Generally, treatment in patients with OCD encompasses psychological and pharmacological approaches.

- Psychological Interventions

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is regarded as the most beneficial psychotherapy for OCD, and when performed by experienced practitioners, may even be the most effective treatment amongst all types of treatments, including pharmacotherapy (35–39). It involves 2 sections: cognitive reappraisal and behavioral interventions, usually in the fashion of exposure-response prevention (38,39).

- Pharmacotherapy

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first-line pharmacological treatment for OCD due to their safety, tolerability, efficacy, and lack of abuse potential (40). Normally higher SSRI doses are used in OCD patients than in patients with anxiety disorders or major depression (41). Concerning treatment efficacy, guidelines outline that a period of 8–12 weeks is the optimal recommended duration of an SSRI trial (36,40,42). After reaching remission, the suggested maintenance duration of pharmacotherapy is a minimum of 12–24 months (43), although, longer treatment may be necessary for many patients due to the risk of relapse after discontinuing medication (44). Another agent that may be used in the treatment of OCD is Clomipramine; a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) which was the first agent to show efficacy in OCD treatment (45). Due to its various side effects, clomipramine is no longer considered as first-line pharmacotherapy for OCD (46).

In patients that fail to fully respond to first-line treatment, multiple approaches exist. These include CBT and SSRI combination therapy (47), switching to a different SSRI, using a higher dose of the maximum recommended dose, a trial of a serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (48–52), and SSRI augmentation with antipsychotics, clomipramine, or glutamatergic agents (53–56). Finally, neuromodulation and neurosurgery can be a last resort option for patients with treatment-resistant OCD (16).

Prognosis

Overall, the long-term outcomes in OCD patients are not entirely hopeless as at least half the treatment-seeking patients exhibit symptomatic remission (57). However, when left untreated, OCD is often chronic with waxing and waning symptoms (58,59). Only 5% to 10% have spontaneous remission(59,60), and another 5% to 10% encounter progressive worsening of their symptoms(60).