Topic: Somnambulism (sleepwalking)

Author: Balqees Ibrahim Abo Awwad

Editor: Ihda Mahmoud Bani Khalaf

Reviewer: Ethar Hazaimeh

Keywords: somnambulism, sleepwalking, parasomnias, DSM-5, sleep disorders.

Introduction

Sleepwalking, a captivating and mysterious occurrence, is but one component within the complex spectrum of parasomnias. What is medically known as somnambulism, refers to the occurrence of undesirable actions such as walking during abrupt but brief awakenings from deep non-rapid eye movement (NREM) slow-wave sleep. [1] Somnambulism presents several characteristic features, including incomplete arousal during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, typically occurring in the earlier stages of the night. Individuals may or may not recall dream content associated with their actions, which can range from simple to complex movements that align with dream scenarios. There is often a diminished awareness of the environment, accompanied by impaired decision-making, planning, and problem-solving skills. [2]

Additionally, somnambulism frequently coexists with other sleep disorders such as rhythmic movement disorders, night terrors in children, somniloquy (sleep talking), and bruxism (teeth grinding). It can also contribute to daytime fatigue and emotional and behavioral issues, particularly in children. [3]

Etiology and risk factors

There is compelling evidence suggesting a genetic predisposition for sleepwalking in certain individuals, with monozygotic twins exhibiting a higher likelihood of somnambulism compared to dizygotic twins. [4] Furthermore, studies have found that a greater proportion of Whites with somnambulism carry the DQB1*0501 gene, indicating a potential link between DQB1 genes and motor disorders during sleep. [5] Research also suggests that sleepwalking may follow an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with reduced penetrance. [6] Many factors can contribute to sleepwalking, including sleep deprivation, stress, and fever. And sometimes sleepwalking can be triggered by underlying conditions that interfere with sleep, such as: sleep disordered breathing, additionally, certain medications—including antibiotics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, lithium, antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), quinine, beta-blockers, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)—have been identified as triggers for sleepwalking episodes, particularly in individuals without a prior history of somnambulism. Substance use (such as alcohol, restless legs syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Additionally, hyperthyroidism has been implicated as a potential cause of sleepwalking in some cases. [7] [8]

Pathophysiology

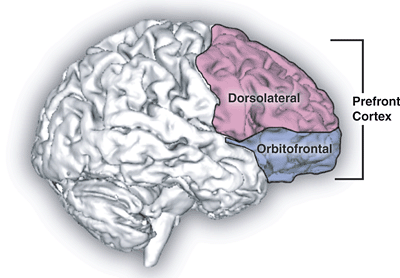

Somnambulism, commonly viewed as either a disorder of arousal or slow-wave sleep, manifests as incomplete awakenings marked by autonomic and motor arousals. EEG patterns show disrupted slow-wave sleep, with increased arousal and decreased activity. Genetic predispositions and factors like irregular sleep schedules or sleep-disordered breathing exacerbate this condition. It reflects a complex interplay between sleep and wakefulness, leaving individuals in a state neither fully awake nor asleep. Studies indicate abnormal arousal reactions rather than difficulty in awakening from deep sleep. Developing theories indicate somnambulism stems from an imbalance in local brain networks governing both states, challenging the predominant view of it as an arousal disorder. Furthermore, research indicates altered regional cerebral blood flow patterns, particularly in frontal and parietal regions, during wakefulness in somnambulistic patients, potentially contributing to daytime functional impairments. This multifaceted understanding underscores the intricate pathophysiology of somnambulism. [9] [10]

Clinical presentation

Many patients with sleepwalking have a history of experiencing episodes that they cannot recall, often reported by witnesses. In some cases, family members may observe sleepwalking episodes and note actions such as rearranging belongings in the room. Reports also include instances of concurrent sleep talking and inappropriate sexual behavior during sleep. Additionally, there are accounts of patients waking up to find leftover food in the kitchen, indicating nocturnal activity. These behaviors tend to occur sporadically, and patients typically do not seek immediate medical assistance. Physical examinations typically yield no specific findings in the majority of cases. [2]

Diagnosis

Aside from sleepwalking, there are several other sleep disorders that clinicians may consider during the diagnostic process to differentiate and rule out alternative explanations for nighttime behaviors.

To properly address and manage sleepwalking, clinicians rely on established diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition).

The DSM-5 delineates specific criteria for diagnosing sleepwalking disorder, categorized under parasomnias. According to the DSM-5, the primary diagnostic criteria for sleepwalking disorder include:

- Recurrent episodes: sleepwalking is characterized by recurrent episodes of incomplete awakening from sleep, typically occurring during the first third of the major sleep episode. These episodes are often accompanied by one or both of the following: sleepwalking, and sleep terrors.

- Amnesia: Individuals experiencing sleepwalking episodes typically exhibit amnesia for the events that occurred during the episode.

- Distress or impairment: Sleepwalking episodes must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other crucial areas of functioning.

- Exclusion of Other Causes: The disturbance should not be attributable solely to the physiological effects of substances or another medical condition.

- coexisting Disorders: The sleepwalking episodes should not be better explained by another sleep disorder, such as sleep-related seizure disorder, insomnia disorder, or rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. [11]

Treatment and management

Somnambulism, a commonly occurring arousal disorder, is typically considered benign and often does not necessitate treatment. No clinical studies have been carried out to assess the efficacy of somnambulism treatments to date. [12] However, in cases where sleepwalking causes distress to the patient or their family, interventions such as scheduled waking up or hypnosis have shown promising results with minimal adverse effects. Scheduled waking up involves rousing the patient 15-30 minutes before their usual sleepwalking time, while hypnosis utilizes suggestions that the patient will awaken upon touching the ground with their feet, both aimed at interrupting the sleepwalking cycle. [2]

These interventions should be consistently practiced daily for two to three weeks. Safety measures, including securing windows and external doors and removing breakable objects, are recommended to reduce the risk of injury. While no medications are specifically approved for treating sleepwalking, clinical experience suggests potential benefits from gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) enhancing agents like clonazepam or gabapentin when taken one hour before sleep. [7]

Complications

Sleepwalking, while often considered harmless and carries a favorable prognosis, can pose several potential complications. One significant concern is the risk of injury during episodes, as sleepwalkers may engage in activities such as walking downstairs, opening windows, or even attempting to drive a vehicle. Additionally, sleepwalking can disrupt the quality of sleep for both the individual experiencing the episodes and their household members, leading to daytime fatigue, impaired cognitive function, and decreased overall well-being. In some cases, sleepwalking may be indicative of an underlying sleep disorder or psychological condition that requires attention and treatment. [13] Moreover, the embarrassment or social stigma associated with sleepwalking episodes can impact an individual’s psychological health and interpersonal relationships. Fortunately, children typically see an improvement in sleepwalking behavior as they reach adolescence, often without the need for interventions or medications. [14]

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has provided insights into sleepwalking, explaining its definition, presentation, diagnosis approach, and treatment. By delineating the diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-5, clinicians are better equipped to identify and differentiate sleepwalking from other sleep disorders. Effective management strategies, including behavioral interventions and addressing underlying factors, play a pivotal role in reducing the impact of sleepwalking on individuals’ daily lives. Moving forward, we hope for continued advancements in research and collaborative efforts aimed at refining diagnostic techniques and developing targeted treatments to improve outcomes for those affected by sleepwalking.